"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Butterfly in the Prison Yard.md\"> The Butterfly in the Prison Yard </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Great Serengeti Land Grab.md\"> The Great Serengeti Land Grab </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Vital City Jimmy Breslin and the Lost Rhythm of New York.md\"> Vital City Jimmy Breslin and the Lost Rhythm of New York </a>",

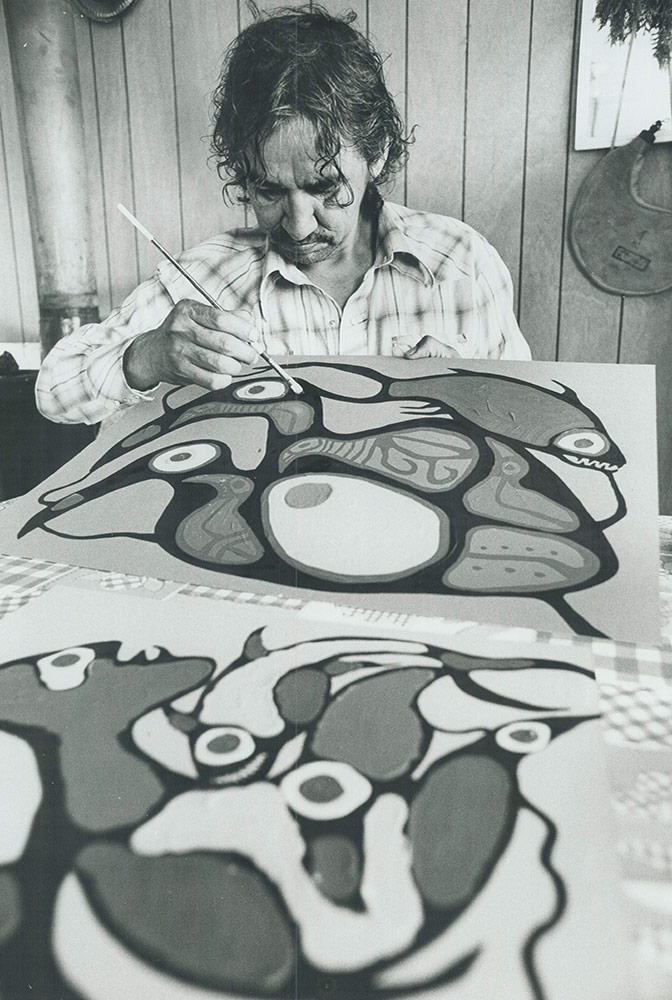

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The “Multi-Multi-Multi-Million-Dollar” Art Fraud That Shook the World.md\"> The “Multi-Multi-Multi-Million-Dollar” Art Fraud That Shook the World </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Russia, Ukraine, and the Coming Schism in Orthodox Christianity.md\"> Russia, Ukraine, and the Coming Schism in Orthodox Christianity </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/A Family’s Disappearance Rocked New Zealand. What Came After Has Stunned Everyone..md\"> A Family’s Disappearance Rocked New Zealand. What Came After Has Stunned Everyone. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/How a Case Against Fox News Tore Apart a Media-Fighting Law Firm.md\"> How a Case Against Fox News Tore Apart a Media-Fighting Law Firm </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Exile on Main St (by The Rolling Stones - 1972).md\"> Exile on Main St (by The Rolling Stones - 1972) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The last days of Boston Market.md\"> The last days of Boston Market </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The soft life why millennials are quitting the rat race.md\"> The soft life why millennials are quitting the rat race </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Welcome to Northwestern University at Stateville.md\"> Welcome to Northwestern University at Stateville </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Cabaret’s Endurance Run The Untold History.md\"> Cabaret’s Endurance Run The Untold History </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/They came for Florida's sun and sand. They got soaring costs and a culture war..md\"> They came for Florida's sun and sand. They got soaring costs and a culture war. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/This is how reporters documented 1,000 deaths after police force that isn't supposed to be fatal.md\"> This is how reporters documented 1,000 deaths after police force that isn't supposed to be fatal </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Right-Wing Media and the Death of an Alabama Pastor An American Tragedy.md\"> Right-Wing Media and the Death of an Alabama Pastor An American Tragedy </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Who Is Podcast Guest Turned Star Andrew Huberman, Really.md\"> Who Is Podcast Guest Turned Star Andrew Huberman, Really </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Their Eyes Were Watching God.md\"> Their Eyes Were Watching God </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/East Goes West.md\"> East Goes West </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Great American Novels.md\"> The Great American Novels </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/A Mistake in a Tesla and a Panicked Final Call The Death of Angela Chao.md\"> A Mistake in a Tesla and a Panicked Final Call The Death of Angela Chao </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/‘We wanted to invade media’ the hippies, nerds and Hollywood pros who brought The Simpsons to life.md\"> ‘We wanted to invade media’ the hippies, nerds and Hollywood pros who brought The Simpsons to life </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Inside the Glorious Afterlife of Roger Federer.md\"> Inside the Glorious Afterlife of Roger Federer </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Battle Over California Squatters Rights in Beverly Hills.md\"> The Battle Over California Squatters Rights in Beverly Hills </a>",

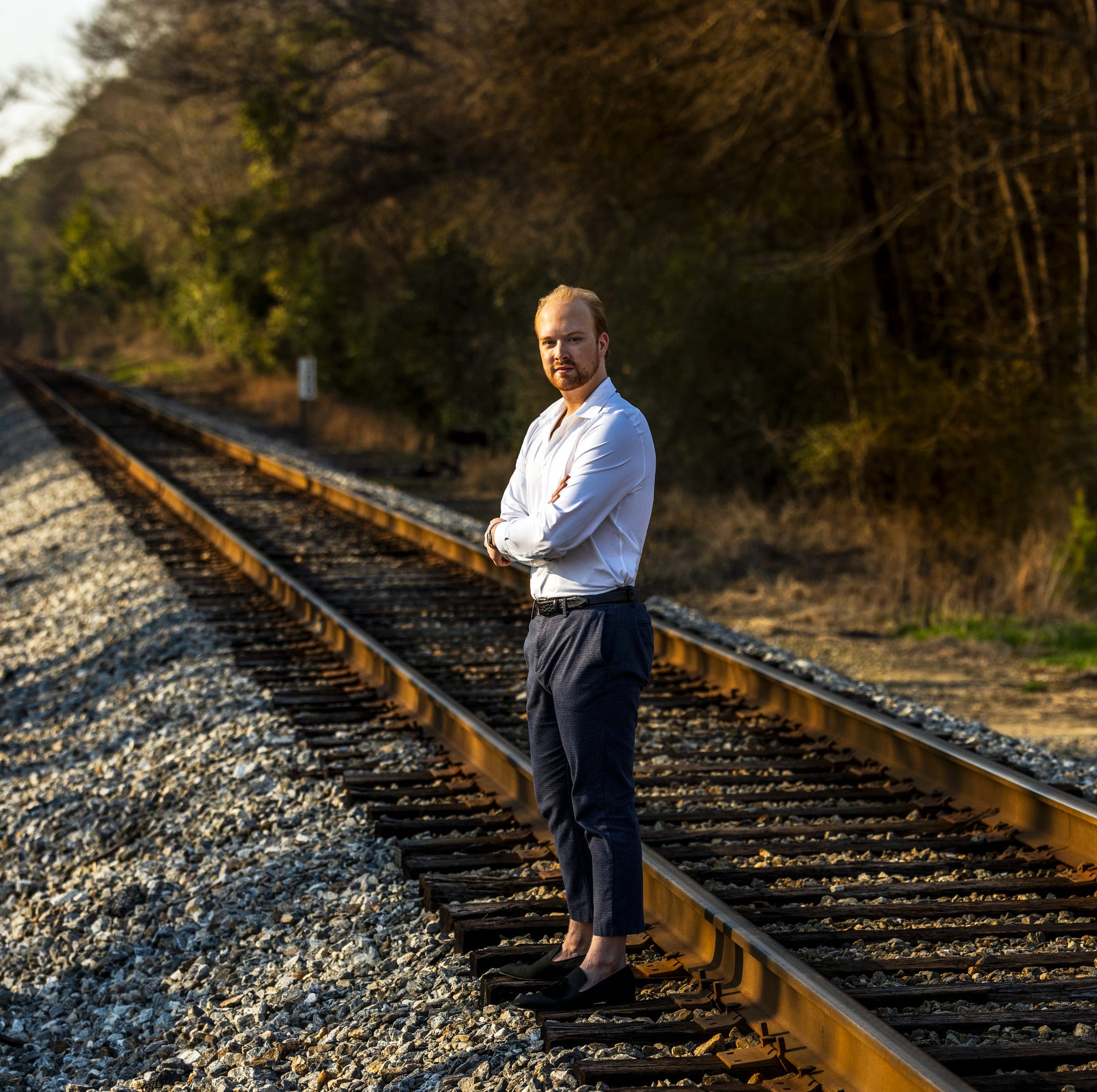

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/How Jesse Plemons Came to Star in, Well, Pretty Much Everything.md\"> How Jesse Plemons Came to Star in, Well, Pretty Much Everything </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/On popular online platforms, predatory groups coerce children into self-harm.md\"> On popular online platforms, predatory groups coerce children into self-harm </a>"

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Butterfly in the Prison Yard.md\"> The Butterfly in the Prison Yard </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Great Serengeti Land Grab.md\"> The Great Serengeti Land Grab </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Vital City Jimmy Breslin and the Lost Rhythm of New York.md\"> Vital City Jimmy Breslin and the Lost Rhythm of New York </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The “Multi-Multi-Multi-Million-Dollar” Art Fraud That Shook the World.md\"> The “Multi-Multi-Multi-Million-Dollar” Art Fraud That Shook the World </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Russia, Ukraine, and the Coming Schism in Orthodox Christianity.md\"> Russia, Ukraine, and the Coming Schism in Orthodox Christianity </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/A Family’s Disappearance Rocked New Zealand. What Came After Has Stunned Everyone..md\"> A Family’s Disappearance Rocked New Zealand. What Came After Has Stunned Everyone. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.05 Vinyls/Exile on Main St (by The Rolling Stones - 1972).md\"> Exile on Main St (by The Rolling Stones - 1972) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"01.07 Animals/2024-04-11 First exercice.md\"> 2024-04-11 First exercice </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The last days of Boston Market.md\"> The last days of Boston Market </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The soft life why millennials are quitting the rat race.md\"> The soft life why millennials are quitting the rat race </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Welcome to Northwestern University at Stateville.md\"> Welcome to Northwestern University at Stateville </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Cabaret’s Endurance Run The Untold History.md\"> Cabaret’s Endurance Run The Untold History </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/They came for Florida's sun and sand. They got soaring costs and a culture war..md\"> They came for Florida's sun and sand. They got soaring costs and a culture war. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/This is how reporters documented 1,000 deaths after police force that isn't supposed to be fatal.md\"> This is how reporters documented 1,000 deaths after police force that isn't supposed to be fatal </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Right-Wing Media and the Death of an Alabama Pastor An American Tragedy.md\"> Right-Wing Media and the Death of an Alabama Pastor An American Tragedy </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Who Is Podcast Guest Turned Star Andrew Huberman, Really.md\"> Who Is Podcast Guest Turned Star Andrew Huberman, Really </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.04 Cinematheque/Arrested Development (2003-2019).md\"> Arrested Development (2003-2019) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.04 Cinematheque/The Last Temptation of Christ (1988).md\"> The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.04 Cinematheque/The Last Temptation of Cheist (1988).md\"> The Last Temptation of Cheist (1988) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"02.03 Zürich/Bei Moudi.md\"> Bei Moudi </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"01.07 Animals/2024-04-02 Arrival at PPZ.md\"> 2024-04-02 Arrival at PPZ </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"01.07 Animals/2023-05-02 Arrival at PPZ.md\"> 2023-05-02 Arrival at PPZ </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/I have little time left. I hope my goodbye inspires you..md\"> I have little time left. I hope my goodbye inspires you. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Great American Novels.md\"> The Great American Novels </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/‘We wanted to invade media’ the hippies, nerds and Hollywood pros who brought The Simpsons to life.md\"> ‘We wanted to invade media’ the hippies, nerds and Hollywood pros who brought The Simpsons to life </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Inside the Glorious Afterlife of Roger Federer.md\"> Inside the Glorious Afterlife of Roger Federer </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Battle Over California Squatters Rights in Beverly Hills.md\"> The Battle Over California Squatters Rights in Beverly Hills </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How Jesse Plemons Came to Star in, Well, Pretty Much Everything.md\"> How Jesse Plemons Came to Star in, Well, Pretty Much Everything </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/On popular online platforms, predatory groups coerce children into self-harm.md\"> On popular online platforms, predatory groups coerce children into self-harm </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/A Bullshit Genius.md\"> A Bullshit Genius </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.01 Reading list/La Louisiane.md\"> La Louisiane </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Gangsters, Money and Murder How Chinese Organized Crime Is Dominating America’s Illegal Marijuana Market.md\"> Gangsters, Money and Murder How Chinese Organized Crime Is Dominating America’s Illegal Marijuana Market </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Jan Marsalek an Agent for Russia The Double Life of the former Wirecard Executive.md\"> Jan Marsalek an Agent for Russia The Double Life of the former Wirecard Executive </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/One woman saw the Great Recession coming. Wall Street's boys club ignored her..md\"> One woman saw the Great Recession coming. Wall Street's boys club ignored her. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Joe Biden’s Last Campaign.md\"> Joe Biden’s Last Campaign </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Dear Caitlin Clark ….md\"> Dear Caitlin Clark … </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.02 Travels/11 Remote Destinations That Are Definitely Worth the Effort to Visit.md\"> 11 Remote Destinations That Are Definitely Worth the Effort to Visit </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.01 Reading list/Invisible Man.md\"> Invisible Man </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.01 Admin/Calendars/Events/2024-03-05 ⚽️ Real Sociedad - PSG (1-2).md\"> 2024-03-05 ⚽️ Real Sociedad - PSG (1-2) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Spy War How the C.I.A. Secretly Helps Ukraine Fight Putin.md\"> The Spy War How the C.I.A. Secretly Helps Ukraine Fight Putin </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Spy War How the C.I.A. Secretly Helps Ukraine Fight Putin.md\"> The Spy War How the C.I.A. Secretly Helps Ukraine Fight Putin </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Pentagon’s Silicon Valley Problem, by Andrew Cockburn.md\"> The Pentagon’s Silicon Valley Problem, by Andrew Cockburn </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Great Pretenders How two faux-Inuit sisters cashed in on a life of deception.md\"> The Great Pretenders How two faux-Inuit sisters cashed in on a life of deception </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/I always believed my funny, kind father was killed by a murderous teenage gang. Three decades on, I discovered the truth.md\"> I always believed my funny, kind father was killed by a murderous teenage gang. Three decades on, I discovered the truth </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The (Many) Vintages of the Century.md\"> The (Many) Vintages of the Century </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How Russian Spies Get Flipped or Expelled, As Told by a Spycatcher.md\"> How Russian Spies Get Flipped or Expelled, As Told by a Spycatcher </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How Russian Spies Get Flipped or Expelled, As Told by a Spycatcher - VSquare.org.md\"> How Russian Spies Get Flipped or Expelled, As Told by a Spycatcher - VSquare.org </a>"

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Inside the Glorious Afterlife of Roger Federer.md\"> Inside the Glorious Afterlife of Roger Federer </a>"

],

"Tagged":[

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/2023-05-02 Arrival at PPZ.md\"> 2023-05-02 Arrival at PPZ </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/I have little time left. I hope my goodbye inspires you..md\"> I have little time left. I hope my goodbye inspires you. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/I am dying at age 49. Here’s why I have no regrets..md\"> I am dying at age 49. Here’s why I have no regrets. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/‘The whole bridge just fell down.’ The final minutes before the Key Bridge collapsed.md\"> ‘The whole bridge just fell down.’ The final minutes before the Key Bridge collapsed </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Evan Gershkovich’s Stolen Year in a Russian Jail.md\"> Evan Gershkovich’s Stolen Year in a Russian Jail </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Masters of the Green The Black Caddies of Augusta National.md\"> Masters of the Green The Black Caddies of Augusta National </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"02.03 Zürich/Le Mezzerie.md\"> Le Mezzerie </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Great American Novels.md\"> The Great American Novels </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/‘We wanted to invade media’ the hippies, nerds and Hollywood pros who brought The Simpsons to life.md\"> ‘We wanted to invade media’ the hippies, nerds and Hollywood pros who brought The Simpsons to life </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/‘We wanted to invade media’ the hippies, nerds and Hollywood pros who brought The Simpsons to life.md\"> ‘We wanted to invade media’ the hippies, nerds and Hollywood pros who brought The Simpsons to life </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Inside the Glorious Afterlife of Roger Federer.md\"> Inside the Glorious Afterlife of Roger Federer </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Battle Over California Squatters Rights in Beverly Hills.md\"> The Battle Over California Squatters Rights in Beverly Hills </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How Jesse Plemons Came to Star in, Well, Pretty Much Everything.md\"> How Jesse Plemons Came to Star in, Well, Pretty Much Everything </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/On popular online platforms, predatory groups coerce children into self-harm.md\"> On popular online platforms, predatory groups coerce children into self-harm </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/A Bullshit Genius.md\"> A Bullshit Genius </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Gangsters, Money and Murder How Chinese Organized Crime Is Dominating America’s Illegal Marijuana Market.md\"> Gangsters, Money and Murder How Chinese Organized Crime Is Dominating America’s Illegal Marijuana Market </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Joe Biden’s Last Campaign.md\"> Joe Biden’s Last Campaign </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/One woman saw the Great Recession coming. Wall Street's boys club ignored her..md\"> One woman saw the Great Recession coming. Wall Street's boys club ignored her. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Jan Marsalek an Agent for Russia The Double Life of the former Wirecard Executive.md\"> Jan Marsalek an Agent for Russia The Double Life of the former Wirecard Executive </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.02 Travels/11 Remote Destinations That Are Definitely Worth the Effort to Visit.md\"> 11 Remote Destinations That Are Definitely Worth the Effort to Visit </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Dear Caitlin Clark ….md\"> Dear Caitlin Clark … </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/I always believed my funny, kind father was killed by a murderous teenage gang. Three decades on, I discovered the truth.md\"> I always believed my funny, kind father was killed by a murderous teenage gang. Three decades on, I discovered the truth </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Great Pretenders How two faux-Inuit sisters cashed in on a life of deception.md\"> The Great Pretenders How two faux-Inuit sisters cashed in on a life of deception </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Pentagon’s Silicon Valley Problem, by Andrew Cockburn.md\"> The Pentagon’s Silicon Valley Problem, by Andrew Cockburn </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How Russian Spies Get Flipped or Expelled, As Told by a Spycatcher.md\"> How Russian Spies Get Flipped or Expelled, As Told by a Spycatcher </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The (Many) Vintages of the Century.md\"> The (Many) Vintages of the Century </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Invisible Man.md\"> Invisible Man </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The surreal life of a professional bridesmaid - The Hustle.md\"> The surreal life of a professional bridesmaid - The Hustle </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How a Con Man Ended Up in Solitary in Colorado Supermax Federal Prison.md\"> How a Con Man Ended Up in Solitary in Colorado Supermax Federal Prison </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/As a Son Risks His Life to Topple the King, His Father Guards the Throne.md\"> As a Son Risks His Life to Topple the King, His Father Guards the Throne </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Recovering the Lost Aviators of World War II.md\"> Recovering the Lost Aviators of World War II </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The surreal life of a professional bridesmaid - The Hustle.md\"> The surreal life of a professional bridesmaid - The Hustle </a>"

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Butterfly in the Prison Yard.md\"> The Butterfly in the Prison Yard </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The “Multi-Multi-Multi-Million-Dollar” Art Fraud That Shook the World.md\"> The “Multi-Multi-Multi-Million-Dollar” Art Fraud That Shook the World </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Vital City Jimmy Breslin and the Lost Rhythm of New York.md\"> Vital City Jimmy Breslin and the Lost Rhythm of New York </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Great Serengeti Land Grab.md\"> The Great Serengeti Land Grab </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/A Family’s Disappearance Rocked New Zealand. What Came After Has Stunned Everyone..md\"> A Family’s Disappearance Rocked New Zealand. What Came After Has Stunned Everyone. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Russia, Ukraine, and the Coming Schism in Orthodox Christianity.md\"> Russia, Ukraine, and the Coming Schism in Orthodox Christianity </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.05 Vinyls/Exile on Main St (by The Rolling Stones - 1972).md\"> Exile on Main St (by The Rolling Stones - 1972) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.01 Reading list/American Psycho.md\"> American Psycho </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.03 Food & Wine/Big Shells With Spicy Lamb Sausage and Pistachios.md\"> Big Shells With Spicy Lamb Sausage and Pistachios </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"01.07 Animals/2024-04-11 First exercice.md\"> 2024-04-11 First exercice </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The soft life why millennials are quitting the rat race.md\"> The soft life why millennials are quitting the rat race </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The last days of Boston Market.md\"> The last days of Boston Market </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Welcome to Northwestern University at Stateville.md\"> Welcome to Northwestern University at Stateville </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/This is how reporters documented 1,000 deaths after police force that isn't supposed to be fatal.md\"> This is how reporters documented 1,000 deaths after police force that isn't supposed to be fatal </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/They came for Florida's sun and sand. They got soaring costs and a culture war..md\"> They came for Florida's sun and sand. They got soaring costs and a culture war. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Cabaret’s Endurance Run The Untold History.md\"> Cabaret’s Endurance Run The Untold History </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Who Is Podcast Guest Turned Star Andrew Huberman, Really.md\"> Who Is Podcast Guest Turned Star Andrew Huberman, Really </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Right-Wing Media and the Death of an Alabama Pastor An American Tragedy.md\"> Right-Wing Media and the Death of an Alabama Pastor An American Tragedy </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/How a Case Against Fox News Tore Apart a Media-Fighting Law Firm.md\"> How a Case Against Fox News Tore Apart a Media-Fighting Law Firm </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/‘Yo Soy la Mamá’ A Migrant Mother’s Struggle to Get Back Her Son.md\"> ‘Yo Soy la Mamá’ A Migrant Mother’s Struggle to Get Back Her Son </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How a Script Doctor Found His Own Voice 1.md\"> How a Script Doctor Found His Own Voice 1 </a>",

@ -12299,167 +12450,166 @@

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Meet the World's Top 'Chess Detective'.md\"> Meet the World's Top 'Chess Detective' </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Bad Faith at Second Mesa.md\"> Bad Faith at Second Mesa </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How the Record Industry Ruthlessly Punished Milli Vanilli for Anticipating the Future of Music.md\"> How the Record Industry Ruthlessly Punished Milli Vanilli for Anticipating the Future of Music </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/I have little time left. I hope my goodbye inspires you..md\"> I have little time left. I hope my goodbye inspires you. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/I am dying at age 49. Here’s why I have no regrets..md\"> I am dying at age 49. Here’s why I have no regrets. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/‘The whole bridge just fell down.’ The final minutes before the Key Bridge collapsed.md\"> ‘The whole bridge just fell down.’ The final minutes before the Key Bridge collapsed </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/‘Yo Soy la Mamá’ A Migrant Mother’s Struggle to Get Back Her Son.md\"> ‘Yo Soy la Mamá’ A Migrant Mother’s Struggle to Get Back Her Son </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Evan Gershkovich’s Stolen Year in a Russian Jail.md\"> Evan Gershkovich’s Stolen Year in a Russian Jail </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Masters of the Green The Black Caddies of Augusta National.md\"> Masters of the Green The Black Caddies of Augusta National </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Gangsters, Money and Murder How Chinese Organized Crime Is Dominating America’s Illegal Marijuana Market.md\"> Gangsters, Money and Murder How Chinese Organized Crime Is Dominating America’s Illegal Marijuana Market </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Butterfly in the Prison Yard.md\"> The Butterfly in the Prison Yard </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The “Multi-Multi-Multi-Million-Dollar” Art Fraud That Shook the World.md\"> The “Multi-Multi-Multi-Million-Dollar” Art Fraud That Shook the World </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Vital City Jimmy Breslin and the Lost Rhythm of New York.md\"> Vital City Jimmy Breslin and the Lost Rhythm of New York </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Great Serengeti Land Grab.md\"> The Great Serengeti Land Grab </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/A Family’s Disappearance Rocked New Zealand. What Came After Has Stunned Everyone..md\"> A Family’s Disappearance Rocked New Zealand. What Came After Has Stunned Everyone. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Russia, Ukraine, and the Coming Schism in Orthodox Christianity.md\"> Russia, Ukraine, and the Coming Schism in Orthodox Christianity </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How Jesse Plemons Came to Star in, Well, Pretty Much Everything.md\"> How Jesse Plemons Came to Star in, Well, Pretty Much Everything </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.05 Vinyls/Exile on Main St (by The Rolling Stones - 1972).md\"> Exile on Main St (by The Rolling Stones - 1972) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"01.07 Animals/2024-04-11 First exercice.md\"> 2024-04-11 First exercice </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The soft life why millennials are quitting the rat race.md\"> The soft life why millennials are quitting the rat race </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The last days of Boston Market.md\"> The last days of Boston Market </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Welcome to Northwestern University at Stateville.md\"> Welcome to Northwestern University at Stateville </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/This is how reporters documented 1,000 deaths after police force that isn't supposed to be fatal.md\"> This is how reporters documented 1,000 deaths after police force that isn't supposed to be fatal </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/They came for Florida's sun and sand. They got soaring costs and a culture war..md\"> They came for Florida's sun and sand. They got soaring costs and a culture war. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Cabaret’s Endurance Run The Untold History.md\"> Cabaret’s Endurance Run The Untold History </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Who Is Podcast Guest Turned Star Andrew Huberman, Really.md\"> Who Is Podcast Guest Turned Star Andrew Huberman, Really </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Right-Wing Media and the Death of an Alabama Pastor An American Tragedy.md\"> Right-Wing Media and the Death of an Alabama Pastor An American Tragedy </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.03 Food & Wine/Sidamo Bio.md\"> Sidamo Bio </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Inside the Meltdown at CNN.md\"> Inside the Meltdown at CNN </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/This Maine Fish House Is an Icon. But of What, Exactly.md\"> This Maine Fish House Is an Icon. But of What, Exactly </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Inside Foxconn’s struggle to make iPhones in India.md\"> Inside Foxconn’s struggle to make iPhones in India </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Miseducation of Maria Montessori.md\"> The Miseducation of Maria Montessori </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Rape, Race and a Decades-Old Lie That Still Wounds.md\"> Rape, Race and a Decades-Old Lie That Still Wounds </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How a Sexual Assault Case in St. John’s Exposed a Police Force’s Predatory Culture.md\"> How a Sexual Assault Case in St. John’s Exposed a Police Force’s Predatory Culture </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Source Years.md\"> The Source Years </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Country Music’s Culture Wars and the Remaking of Nashville.md\"> Country Music’s Culture Wars and the Remaking of Nashville </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"06.02 Investments/Helium creates an open source, decentralized future for the web.md\"> Helium creates an open source, decentralized future for the web </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.01 Reading list/Le Temps gagné.md\"> Le Temps gagné </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.01 Reading list/Seven Pillars of Wisdom.md\"> Seven Pillars of Wisdom </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.01 Reading list/Tous les Hommes n'habitent pas le Monde de la meme Facon.md\"> Tous les Hommes n'habitent pas le Monde de la meme Facon </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.01 Reading list/Keila la Rouge.md\"> Keila la Rouge </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.01 Reading list/Sad Little Men.md\"> Sad Little Men </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.01 Reading list/La Prochaine Fois que tu Mordras la Poussière.md\"> La Prochaine Fois que tu Mordras la Poussière </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"06.02 Investments/Helium creates an open source, decentralized future for the web.md\"> Helium creates an open source, decentralized future for the web </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"06.02 Investments/Airbus.md\"> Airbus </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.04 IT/How to migrate your Nextcloud database-backend from MySQLMariaDB to PostgreSQL.md\"> How to migrate your Nextcloud database-backend from MySQLMariaDB to PostgreSQL </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.04 IT/How to sync Obsidian Notes on iOS.md\"> How to sync Obsidian Notes on iOS </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.04 IT/GitHub - stefanprodandockprom Docker hosts and containers monitoring with Prometheus, Grafana, cAdvisor, NodeExporter and AlertManager.md\"> GitHub - stefanprodandockprom Docker hosts and containers monitoring with Prometheus, Grafana, cAdvisor, NodeExporter and AlertManager </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.04 IT/GitHub - RunaCapitalawesome-oss-alternatives Awesome list of open-source startup alternatives to well-known SaaS products 🚀.md\"> GitHub - RunaCapitalawesome-oss-alternatives Awesome list of open-source startup alternatives to well-known SaaS products 🚀 </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.04 IT/GitHub - postalserverpostal ✉️ A fully featured open source mail delivery platform for incoming & outgoing e-mail.md\"> GitHub - postalserverpostal ✉️ A fully featured open source mail delivery platform for incoming & outgoing e-mail </a>"

"title":":hibiscus: :fork_and_knife: [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Book a restaurant with terrace for the season: [[Albishaus]], [[Restaurant Boldern]], [[Zur Buech]], [[Jardin Zürichberg]], [[Bistro Rigiblick]], [[Portofino am See]], [[La Réserve|La Muña]] %%done_del%%",

@ -846,7 +841,7 @@

{

"title":":hibiscus: :partying_face: [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Zürich Pride Festival %%done_del%%",

"time":"2024-06-15",

"rowNumber":119

"rowNumber":120

},

{

"title":":sunny: :movie_camera: [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Check out programmation of the [Zurich's finest open-air cinema | Allianz Cinema -](https://zuerich.allianzcinema.ch/en) %%done_del%%",

@ -856,22 +851,22 @@

{

"title":":sunny: :partying_face: [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Check out Seenachtfest Rapperswil-Jona %%done_del%%",

"time":"2024-08-01",

"rowNumber":122

"rowNumber":123

},

{

"title":":sunny: :runner: [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Check out tickets to Weltklasse Zürich %%done_del%%",

"time":"2024-08-01",

"rowNumber":129

"rowNumber":130

},

{

"title":":sunny: :partying_face: [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Street Parade %%done_del%%",

# A Family’s Disappearance Rocked New Zealand. What Came After Has Stunned Everyone.

Illustration by Toby Morris

The waves were already crashing over the Toyota’s hood when they found it.

It was a blustery September Sunday in 2021, and the Hilux pickup sat far down the gray sand in a remote cove on the wild west coast of New Zealand’s North Island. The Māori men who noticed the car live in mobile homes and cabins up by the road, on ancestral land near Kiritehere Beach. The truck was parked below the high-tide line, facing the sea, and was nearly swamped by the waves pummeling the shore. The men found the keys, tucked under the driver’s-side floormat, and backed the car up the beach. They couldn’t help but notice empty child seats strapped into the back. If any kids had gotten close to the sea on a day like this, they were long gone.

The truck, it would turn out, belonged to Tom Phillips, the son of a prominent Pākehā—white—family with a farm nearby in Marokopa. Phillips, 34, spent much of his time on the farm, where he home-schooled his three kids, Jayda, 8, Maverick, 6, and Ember, 5. He’d separated from his wife three years before and had custody of the kids. Locals heard she was down on the South Island, struggling with her own problems.

Now here was his truck, marooned. The next morning, Tom’s brother Ben drove down to the beach. He’d last seen Tom and the kids on Saturday, Sept. 11, when they’d left the farm, heading, everyone thought, back to Ōtorohanga, the inland town where Tom kept a house. Now it was Sept. 13. Ben inspected the Toyota, then called the police.

Soon photos of the missing father and his three smiling children were in every newspaper and on every TV channel in New Zealand. Police and volunteer searchers fanned out over the area, knocking on doors. Helicopters, planes, and heat-detecting drones flew over the deep bush surrounding the beach. Rescue boats and jet skis buzzed through the roaring waves, looking for bodies. On days the sea was calm, swimmers from surf rescue teams explored caves along the shoreline. The local hapū, or Māori clan, cooked hot meals for the searchers in a shed near the beach. Three days into the search, Phillips’ ex-wife [released a careful statement](https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/126382867/mum-holding-out-every-hope-for-children-missing-on-stormy-waikato-beach?rm=a) through the police, thanking the searchers for their efforts. “We are holding out every hope that my children Jayda, Maverick, and Ember are safe,” she said.

But the stark facts—the lonely car on the beach, the 8-foot waves, Tom and the children vanishing completely—were daunting. “I do fear the worst,” Tom’s sister, Rozzi Pethybridge, told a reporter. “I am worried a rogue wave has caught one of the kids and he’s gone in to save them.” Phillips’ uncle seemed to be hinting at something even darker when he told another reporter that in some ways he hoped it *had* been a rogue wave: “If something has happened to the children, the best-case scenario is that they were washed out to sea,” he said. “That way it’s an accident.”

September in New Zealand, the height of Southern Hemisphere spring, is whitebaiting season, when locals set up nets at the river mouth to capture the shoals of immature fish headed back to their freshwater home. But during the search operation, authorities placed a rāhui, a ban, on fishing. Some Marokopa residents grumbled about halting what had been a boom season. But others put things in perspective. “That’s the end of the whitebaiting,” one local [told a reporter](https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/300408397/the-mystery-of-the-missing-family--whats-become-of-tom-phillips-and-his-kids), “but that’s small-time compared with losing a family.”

On social media and on Reddit, observers seized on rumors of a custody dispute and [spun out dark theories](https://www.reddit.com/r/newzealand/comments/puhmqz/missing_family_daily_searches_for_family_last/) of an abduction or staged disappearance. Phillips was an experienced bushman, camper, and hunter. In passing, locals told reporters that if Phillips *had* taken the kids out into the wild for some reason, they were confident he could last for weeks or months out there, even with three children in tow. A week into the search, family members seemed to be pinning their hopes on this idea. “We’re looking on the bright side,” the uncle [told Radio New Zealand](https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/451509/family-hope-missing-dad-and-children-are-in-hiding-uncle-says). “We’re hoping he’s just gone and hidden in the bush.”

After 12 days of active searching, the [police stood down](https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/300415580/missing-family-daily-searches-for-family-last-seen-in-marokopa-suspended). The whitebaiting rāhui was lifted. Emergency services personnel moved out of the Marokopa community building on the banks of the river. Other than the Toyota, not a single sign had been found of the four missing Phillipses. The media continued covering the case, but there wasn’t much to say—everyone understood that until bodies washed up somewhere, it was unlikely there would be any further news.

No one knew that the disappearances were just the beginning of an ordeal that has not yet ended—a case that has only grown stranger and more ominous in the two and a half years since, prompting pleas from family, increasing public astonishment, online speculation, a shocking crime, and a community’s closing ranks around one of its own.

Back in September 2021, the real mystery started when the first one was solved. Because 17 days after they had been reported missing, Tom Phillips and his three children walked through the front door of his parents’ farm.

The Tom Phillips disappearance captivated New Zealand. But the incident never reached the 24/7 fever pitch of blanket coverage that would have characterized the story if it had happened in the United States. In part that’s because there’s no CNN-style 24-hour news channel in New Zealand, though pretty much every outlet in the country sent a reporter to the west coast in hopes of digging something up. But no one had much to say. Phillips’ uncle spoke to press during the search, but other members of the Phillips clan stuck to the farm and stayed away from television cameras. The police delivered a daily briefing most afternoons, which never offered any new information. The children’s mother remained unnamed. Reporters were unable to reveal details of the couple’s custody disputes, because family courts in New Zealand strictly prohibit media from reporting on their proceedings.

Even after Phillips and his children returned, there [was no footage](https://www.newshub.co.nz/home/new-zealand/2021/09/family-missing-in-south-waikato-found-safe-and-well.html) of the happy family waving from the front porch, no soft-focus newsmagazine interviews, no morning-show feature. Phillips never spoke to the press. The family issued a statement—“Tom is remorseful, he is humbled, he is gaining an understanding of the horrific ordeal he has put us through”—and Pethybridge gave a brief interview to the New Zealand Herald in which she [seemed shell-shocked](https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/marokopa-mystery-family-of-missing-kids-on-weeks-in-dense-bush-didnt-do-it-hard-at-all/FGZYKWO6KWPJ4QPBHOQ6WXRRIY/?utm_campaign=nzh_tw&utm_medium=Social&utm_source=Twitter&utm_campaign=nzh_tw#Echobox=1633037862-1) by the situation. “Hope dwindled and we became more and more resigned and sad,” she said. Now, she added, she could “smile and laugh for the first time in three weeks, and not feel bad if you have a little smile.”

The Phillips kids: from left, Maverick, Jayda, and Ember. Courtesy of NZ Police

She did not, however, smile once in the entire interview. The family closed ranks, and reporters were stuck combing social media for clues. (“Pethybridge also shared a song [titled ‘Hey Brother’](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Cp6mKbRTQY) by Swedish DJ Avicci,” one report noted.)

The residents of Marokopa, too, had little to say once the children were safe, one reporter told me. “After he was found, no one wanted to talk,” [said Karen Rutherford](https://newsroom.co.nz/2021/10/04/man-found-mystery-continues/) of Newshub. “He has put people through the wringer, to be honest.” After all, what had all that work been for? They’d served meals to rescuers, opened the community center 24/7. Many residents had tramped along the shoreline, looking for bodies. Even after the police had called off the search, members of the local hapū went out every day. Then it turned out that Phillips simply had not bothered to tell anyone he was taking the children to the deep bush, pitching a tent 15 kilometers south of the beach where his car was found. “He’s done this before. It’s not the first time,” a [local farmer said](https://www.stuff.co.nz/waikato-times/news/300420778/from-joy-to-frustration-over-marokopas-lostthenfound-family). “We’re glad to have him back, but he should be held accountable. What was he thinking?”

And why had he left the car there, anyway? Though one friend suggested that the pickup had been stolen by joyriding kids, most everyone assumed that Phillips had parked on the beach to throw searchers off the trail. But for what purpose? Some [noted Pethybridge’s comment](https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/452625/missing-marokopa-family-found-safe-and-well) that Phillips was in “a helpless place” and wanted to “clear his head.” A [Reddit user mused](https://www.reddit.com/r/newzealand/comments/py73jy/missing_marakopa_family_found_safe_and_well/): “It’s one thing for him wanting to clear his head but what about the kids? Hope they’re OK, might need some therapy stat.” Others leaped in to assure everyone that a trip to the bush was just what any kid needed: “Going camping with dad and forgetting about the rest of the world would be pretty sweet.”

Indeed, there’s a long tradition in New Zealand of valorizing backcountry adventure—getting lost in the bush for a while—shared by parents and children. “It’s a [*Man Alone* thing](https://thespinoff.co.nz/books/29-04-2021/locked-down-and-far-from-home-with-man-alone),” the Auckland education researcher Stuart McNaughton told me, referring to the 1939 novel by John Mulgan still viewed by many as essential to understanding the “Kiwi character.” “Getting on with stuff, taming a difficult environment, getting hurt in the process.” To many New Zealanders, a proper father figure is a guy who knows how to handle the wilderness, a place where increasingly citified Kiwi kids seem less and less comfortable. McNaughton summarized the attitude: “If they’re gonna have an accident, they’re gonna have an accident—it’ll probably do them good.”

The modern urtext on this subject is Taika Waititi’s 2016 comedy [*Hunt for the Wilderpeople*](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hunt_for_the_Wilderpeople), still the most successful locally produced film in the nation’s history. In the movie, a troubled Māori kid from the Auckland streets bonds with a brusque Pākehā outdoorsman in the deep bush. The movie’s villain is a maniacal child protection officer who hunts them down—the overweening nanny state, in the flesh. It’s based on a book by the late Barry Crump, famous for his reputation as a rugged bloke; New Zealanders know him best for [his long-running ads](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pyHBKX29_Q8) for the Toyota Hilux ute, the official truck of bushmen—unsurprisingly, the truck Tom Phillips owned and parked on Kiritehere Beach.

After he returned, [Phillips was charged](https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/126656040/man-charged-over-search-for-father-and-children-in-marokopa-waikato?rm=a) with wasting police resources and ordered to appear in court. He was “reckless as to whether wasteful deployment of police resources would result,” the charges read. He “behaved in a manner that was likely to give rise to serious apprehension for the safety of himself, Jayda Phillips, Ember Phillips and Maverick Phillips, knowing that such apprehension would be groundless.” The charges carried a maximum penalty of three months in jail or a $2,000 fine.

In neighborhood Facebook groups and on playgrounds across New Zealand, parents debated the news. How dare this screw-up risk the lives of searchers and terrify his family because he hadn’t bothered to tell anyone where he was going. Shouldn’t he at least pay the government back for what it spent on that search plane? Or: How dare the government charge a parent for going camping with his children! Wasn’t he the kind of throwback dad we didn’t see enough of anymore, as modern kids become coddled and soft?

I was certainly sympathetic to this second argument. I’d taken my own family to New Zealand to live for a period in 2017, specifically to capture that spirit of adventure, something that felt sorely lacking in our suburban American lives. Our daughters—just a little older than Phillips’ kids were when they disappeared—rarely left their comfort zones, and no one we knew let their children roam our neighborhood freely. We hoped that New Zealand might help shake us up. I was no bushman like Tom Phillips, but the four of us [did go tramping](https://longreads.com/2019/09/17/tramp-like-us/) across graywacke streams, into the forest primeval, even along a remote shore that looked quite a bit like the Marokopa coast. Unlike Phillips, I told my friends where we were going, but still: Were the police really charging this guy for giving his kids what might have been a wondrous adventure?

Reporters, struggling to [advance the story](https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/126543524/the-marokopa-mystery-what-we-still-dont-know-about-the-phillips-familys-disappearance-and-survival), asked experts what they thought about it all. One family lawyer admitted he knew nothing about the children’s custody arrangement but said, “If there was no parenting order, and he was just going on holiday, legally he’s done nothing wrong.” The same outlet asked a “human rights lawyer” what she thought about a parent taking children out into the deep bush without letting anyone know. “It’s not best practice,” she replied, in a tone I could almost hear from the page.

Tom Phillips. Courtesy of NZ Police

Then, in December, as summer vacation season began, the New Zealand Herald found a Facebook post—seemingly from someone close to the children’s mother—stating that Phillips had once again [taken his kids](https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/marokopa-family-missing-again-tom-phillips-and-his-children-havent-been-seen-for-a-week/FJCUY5RR5MG7NTVX6Z4L6NHWZU/) on walkabout. “He notified family of where he was going,” the local police commander said in response. “In terms of current court restrictions of what he can and can’t do, he’s doing nothing wrong.” Commenters online were aghast that the paper had [pursued the story](https://www.reddit.com/r/newzealand/comments/rk40i0/marokopa_family_missing_again_tom_phillips_and/). “So this is just literally a man taking his kids camping?” one wrote. “Correct,” replied another. “His ex-missus has gone to NZH and they’ve run with it.”

Phillips’ scheduled court date was Jan. 12, 2022. That morning, reporters packed the tiny wooden courthouse in Te Kūiti, lured by the chance to finally ask questions of the enigmatic father who had made news and driven debate across the country for months. More media spilled onto Queen Street outside, pacing in the warm summer sun.

Tom Phillips [never showed up](https://www.stuff.co.nz/waikato-times/news/127475663/marokopa-dad-thomas-phillips-a-noshow-in-court-on-charge-of-wasting-police-time). Appearing via video, his lawyer told the judge that he’d informed his client of the appearance date and never spoken to him again. He also asked to withdraw as counsel in the case.

The judge issued a warrant for Phillips’ arrest. But the police couldn’t locate Phillips or his three children. They had disappeared into the bush. And this time, they didn’t come back.

When I spoke to New Zealanders in the months after the second disappearance of Tom Phillips, it was clear that some in the country still viewed him as a kind of quirky folk hero who’d taken his kids out into the wilderness to avoid the oppressive, overreaching government. “There was a lot of talk like that,” said Max Baxter, the mayor of Ōtorohanga, where Phillips’ house sat empty, weeds growing over his fence. “He felt that his personal protection of the children was paramount, and the result was that he was opening them up to experiences that kids nowadays don’t get. He’s teaching them to be bushmen.” He laughed. “My grown children probably couldn’t survive two weeks in the bush!”

“A lot of people are like, ‘Leave him alone, those kids are probably having the time of their lives,’ ” said Karen Rutherford, the New Zealand reporter who got the [only on-camera interview](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z0e5AT4EhTw) with Phillips’ ex-wife. But others, she told me, felt that “now he’s skipped court he’s stuffed all his chances of being a good dad.”

In the United States, I felt my admiration of Phillips wash away like the road to Marokopa [as heavy rains](https://www.stuff.co.nz/waikato-times/news/300516303/marokopa-locals-caught-off-guard-as-rain-dump-floods-the-village) [swept through the region](https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/128843903/marokopa-cut-off-as-floods-make-road-unpassable). Was he really hiding his kids in the bush during *this* kind of weather? The children’s mother made a public [appeal for assistance](https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/468228/desperate-mum-pleads-for-safe-return-of-missing-phillips-children-from-marokopa) in May, as New Zealand winter approached. Other relatives on the mother’s side [launched an online petition](https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/128560653/adult-sisters-of-missing-marokopa-children-launch-petition-asking-authorities-to-do-more-to-find-them) urging police to do more. They complained that Phillips’ parents were refusing to let anyone onto their enormous Marokopa compound to search the wilderness around the farm—or the baches, the guesthouses the family [used to rent out](https://www.oocities.org/marokopa2002/Accommodation.htm) to tourists.

The Phillips family remained silent objects of fascination for the news media. On the day of Phillips’ courthouse no-show, his mother had told reporters assembled outside the gates of the family farm, “I am trespassing all media from this property.” According to one outlet, asked if she knew where her son was, “Julia Phillips simply answered with a shrug and a smile.”

“They’re real sort of rugged, coast-y people who don’t come into town much,” a local reporter told me. “They’re kind of unusual. You’d call them rednecks, I think.” (Being “coastal” has a very different connotation in New Zealand than it does in the U.S.) Tony Wall, a reporter for the newsmagazine Stuff, told me that Phillips’ parents have been “very uncooperative. If you read between the lines, it definitely seems like they know something but they’re not telling us.”

Someone, everybody assumed, was shopping for supplies and ferrying them out to Phillips, wherever he was hiding out. “It’s almost unfathomable to think a father could survive with three small children without someone buying them supplies,” Baxter told me. “But what’s the endgame? I’m looking out my window now, and it’s pouring down rain.”

The lack of urgency on the part of Waikato police was often commented upon. “It’s very strange,” one reporter who’s been covering the case said. “The cops are not pouring any resources into looking for him and those children. I think they are of the view that he’s not going to hurt them and he’ll eventually come out.” The department responded to press requests with a not-particularly-inspiring statement: “Police continue to make enquiries to establish the whereabouts of Tom Phillips, who we believe is currently with his three children. While Police understand the ongoing interest in this matter, we will not be disclosing the details of the enquiries that are under way.”

Whatever enquiries were under way, that cold and wet winter passed with no sign of Tom Phillips. As 2022 turned into 2023, Phillips and his children had been missing without a trace for more than a year. Then came the bank robbery.

The two figures were dressed in all black—motorcycle helmets, puffer jackets, and boots—when they walked into the ANZ bank branch less than half a mile from the courthouse in Te Kūiti, just before noon on May 16, 2023. When the bank’s anxious staff asked them to take their helmets off, the pair displayed guns and demanded money. Tellers quickly gave them cash and, within moments, the pair ran out the front door.

As the robbers hurried down Rora Street, one witness later said they were dropping cash out of their pockets, “heaps of $50 notes.” The street was strewn with money. The confused passerby asked one of them, a slight figure whom they described as “a girl,” if she needed help picking up the money. Up ahead, the girl’s companion—a man, it seemed—turned back to look at what was happening. Right then, he was tackled to the ground by the owner of the SuperValue supermarket they’d been hurrying past.

Courtesy of NZ Police

Suddenly, the girl brandished her gun. The passerby backed away. Someone called, “Fire the gun!” No one’s quite clear who did what, or whom they were aiming at, but someone did fire, more than once. The passerby froze in their tracks, and the supermarket owner retreated.

The robbers ran past a vape shop and around a corner to a parking lot, where they climbed onto a motorbike and rode off to the north. Behind them, bank notes littered the pavement, 20s and 50s—as much as $1,000, one witness estimated.

The armed robbery shocked the town, which bills itself as the nation’s sheepshearing capital. A week later, the robbery led a Waikato Times feature about growing [youth crime concerns](https://www.waikatotimes.co.nz/a/nz-news/350015252/very-country-robbery) in Te Kūiti, full of nervous quotes from residents and shop owners about meth, burglary, and car thefts broadcast on TikTok.

Yet on the subject of the bank robbery itself, one Maōri warden had only to say that he reckoned locals already knew who did it. It wasn’t some wayward Te Kūiti youth or a more organized criminal element. Even in those early days, speculation was running rampant among residents that the bank robbers were, in fact, Tom Phillips—and one of his children.

It took four months for police to [officially name Phillips](https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/300964573/arrest-warrant-issued-for-missing-marokopa-dad-tom-phillips-over-alleged-bank-robbery) for the crime, charging him with aggravated robbery, aggravated wounding, and unlawful possession of a firearm. They believe that he was the larger of the two robbers, the one who seemed to be leading things, and have not identified the second, smaller robber, other than to say that they think she is “female.” At the time of the robbery, Jayda was 10.

The September 2023 charges in the Wild West–style bank robbery—guns blazing, bank notes blowing in the wind—eliminated any residual goodwill Phillips had accumulated in his long months on the run. They capped off an eventful winter, Phillips’ second on the run with his children.

The month before, Phillips had stolen a truck—naturally, a Toyota Hilux—and driven to Hamilton, the biggest city in the Waikato region, about 40 miles north of Ōtorohanga. An acquaintance recognized him in the parking lot of Bunnings, a Home Depot–type home improvement store, where Phillips, [wearing a surgical mask](https://www.odt.co.nz/news/national/police-reveal-items-marakopa-father-bought) and a woolen hat, used a large amount of cash to buy headlamps, batteries, seedlings, buckets, and gumboots.

That evening, Phillips got into an altercation on a road about an hour up the coast from Marokopa. The owner of the Hilux—who had also realized that winter clothing had been stolen from his property—fought with Phillips, then chased him along the winding highway, reportedly attempting to run him off the road. Eventually multiple vehicles were pursuing Phillips, who switched off the Hilux’s headlights and turned sharply into the parking lot of the Te Kauri Lodge, driving through a gate and into a paddock. “He went in there and he hid,” a lodge custodian told [Radio New Zealand](https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/495109/tom-phillips-father-of-missing-marokopa-children-evaded-multiple-pursuers-residents-say). “These fullahs drove straight past.” The police sent out a search helicopter, to no avail. A few days later, the [Hilux was found](https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/300943316/stolen-ute-driven-by-tom-phillips-found-by-police-in-marokopa-bush) deep in the undergrowth, about 25 meters off Marokopa Road, not far from the Phillips farm.

A few weeks later, a private investigator—he tells reporters he “follows the case on his own time”—tipped off Tony Wall, the reporter at Stuff, that the property to which the Hilux was returned had hosted Phillips for a visit the year before. (The P.I. says he reported the sighting to the police but nothing came of it.) According to an informant, Phillips had been receiving help from a network of local residents “since day one.”

Wall chronicled his visit to the steep, densely wooded property near Ōtorohanga in a hair-raising story [published last August](https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/crime/300957682/marokopa-mystery-police-knew-of-possible-fugitive-sighting-last-year-at-property-where-he-later-stole-a-ute). A neighbor, who was reportedly also present when Phillips visited the property in 2022, launched into a coy, taunting conversation about the disappearance. “I can’t say if I have or haven’t seen him in the last few years,” the man said. “It’s like a good game of hide-and-go-seek. He’s fucking good at it. Never, ever play hide-and-go-seek with him because you’ll give up, and he won’t come out.” When Wall asked the man how someone like Phillips could simply vanish, the man scoffed. “It’s easy in New Zealand. The justice system is shit, the court system is shit, the police are shit, the media is shit. That’s the facts of it.”

As Wall drove away, his car was overtaken by two other drivers, who boxed him in and forced him to pull over to the side of the road. One of the vehicles was driven by the owner of the stolen Hilux, who accused Wall of “snooping around” and “causing havoc.” “You’re in the wrong fucking place for this, man,” he said. “You want to come and harass us out here, on my own turf?” He tried to force open Wall’s car door, telling him, “I’m gonna fuck you up, mate.”

Wall finally managed to drive away, but the ute’s owner had one last thing to say. “You’re fucking lucky we’re letting you out of here, cunt. You want the truth about the whole fucking scenario, mate, you’d better be on your game, ’cause you’re pushing shit uphill now.”

After the police named Phillips in the bank robbery, [residents phoned in](https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/missing-marokopa-fugitive-tom-phillips-police-reveal-12-more-sightings/IVMXVESFAZFMNPHP4I72R5NAKQ/) more than a dozen sightings, but the police could never seem to catch him. Late one night in November, Phillips and one of his children rode a stolen quad bike to the town of Piopio and smashed the window of a superette in an attempted burglary, police say. [Security footage showed](https://www.waikatotimes.co.nz/nz-news/350110471/missing-marokopa-dad-tom-phillips-allegedly-used-stolen-quadbike-smashed) a pair dressed in full camo gear approaching the store’s camera with a spray can. When an alarm sounded, they fled south.

This January, the two-year anniversary of Phillips’ second flight passed with just another wan police announcement—this time that [they had narrowed](https://www.stuff.co.nz/nz-news/350155353/police-narrow-marokopa-search-phillips-family) Phillips’ hiding place to the Marokopa area, a development that surprised absolutely no one who’s been following the case. Yet I feel for the police, who are looking in an area spanning hundreds of square miles, where a number of residents clearly still have no desire to share information with them. (The owner of the stolen Hilux—a guy who disliked Phillips enough that he tried to run him off the road—nevertheless referred to the police as “fucking pigshits.”) “If a plane crashed in this bush, you’d be fortunate to find it,” Max Baxter told me. “It’s really, really hard to begin somewhere, unless there’s someone who knows and decides it’s time to come forward.”

Few New Zealanders still believe that Phillips and his kids—now 10, 8, and 7—are roughing it, stalking game in the deep bush like the wilderpeople of old. Most everyone thinks that he’s hiding on or near his family farm, aided by a network of friendly locals that may or may not include his parents. (That’s certainly what Wall, still trying to [crack the case](https://www.stuff.co.nz/nz-news/350166823/could-wanted-man-tom-phillips-be-or-near-his-family-farm), believes.) On social media, it’s been a long time since anyone has called Phillips a good dad merely fighting authority. “He’s just a piece of shit human being with anger and control issues who is subjecting his children to child abuse,” went [one typical comment](https://www.reddit.com/r/newzealand/comments/17upm0f/missing_marokopa_family_in_piopio_tom_phillips/).

And few anticipate any ending to this story that feels happy at all. In the worst-case scenario, Phillips and his kids are injured, or killed, robbing another bank or battling it out with the cops. But even the best-case scenario at this point feels grim. Phillips’ children have spent the past two and a half years with a father who’s surely told them that everyone is out to get them, that they can trust no one but him, that the only way to stay safe is to hide out far from the rest of the world. He’s relayed to them that their future depends on smashing windows, stealing cars, waving guns.

Someday those children will be found, and their father will almost certainly be sent to jail. Every news report about the case—a dwindling number, as the months go on—features the same photos of the children: the girls in fairy dresses, all three of them grinning widely. In the next photos we see of Jayda, Maverick, and Ember, they won’t be smiling. I once thought perhaps their father was giving them a gift, the adventure of a lifetime. Instead, he stole their childhoods. When it’s all over they’ll be as alone as that truck was, parked on the gray sand, the implacable sea rushing up to meet it.

A**s director Rebecca** Frecknall was rehearsing a new cast for her hit London revival of *Cabaret,* the actor playing Clifford Bradshaw, an American writer living in Berlin during the final days of the Weimar Republic, came onstage carrying that day’s newspaper as a prop. It happened to be *Metro,* the free London tabloid commuters read on their way to work. The date was February 25, 2022. When the actor said his line—“We’ve got to leave Berlin—as soon as possible. Tomorrow!”—Frecknall was caught short. She noticed the paper’s headline: “Russia Invades Ukraine.”

*Cabaret,* the groundbreaking 1966 Broadway musical that tackles fascism, antisemitism, abortion, World War II, and the events leading up to the Holocaust, had certainly captured the times once again.

Back in rehearsals four months later, Frecknall and the cast got word that the Supreme Court had overturned *Roe v. Wade.* Every time she checks up on *Cabaret,* “it feels like something else has happened in the world,” she told me over coffee in London in September.

A month later, as Frecknall was preparing her production of *Cabaret* for its Broadway premiere, something else *did* happen: On October 7, Hamas terrorists infiltrated Israel, killing at least 1,200 people and taking more than 240 hostages.

The revival of *Cabaret*—starring [Eddie Redmayne](https://www.vanityfair.com/video/watch/careert-timeline-vf-career-timeline-eddie-redmayne) as the creepy yet seductive Emcee; Gayle Rankin as the gin-swilling nightclub singer Sally Bowles; and Bebe Neuwirth as Fraulein Schneider, a landlady struggling to scrape by—opens April 21 at Manhattan’s August Wilson Theatre. It will do so in the shadow of a pogrom not seen since the *Einsatzgruppen* slaughtered thousands of Jews in Eastern Europe and in the shadow of a war between Israel and Hamas that continues into its fifth month, with the killing of thousands of civilians in Gaza.

Nearly 60 years after its debut, *Cabaret* still stings. That is its brilliance. And its tragedy.

R**edmayne has been** haunted by *Cabaret* ever since he played the Emcee in prep school. “I was staggered by the character,” he says. “The lack of definition of it, the enigma of it.” He played the part again during his first year at Cambridge at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, where nearly 3,500 shoestring productions jostle for attention each summer. *Cabaret,* performed in a tiny venue that “stank,” Redmayne recalls, did well enough that the producers added an extra show. He was leering at the Kit Kat Club girls from 8 p.m. till 10 p.m. and then from 11 p.m. till two in the morning. “You’d wake up at midday. You barely see sunshine. I just became this gaunt, skeletal figure.” His parents came to see him and said, “You need vitamin D!”

In 2021, Redmayne, by then an Oscar winner for *The Theory of Everything* and a Tony winner for *Red,* was playing the Emcee again, this time in Frecknall’s West End production. His dressing room on opening night was full of flowers. There was one bouquet with a card he did not have a chance to open until intermission. It was from [Joel Grey](https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2017/02/cabaret-joel-grey-donald-trump-cautionary-tale-nazis), who originated the role on Broadway and won an Oscar for his performance alongside Liza Minnelli in the 1972 movie. He welcomed the young actor “to the family,” Redmayne says. “It was an extraordinary moment for me.”

*Cabaret* is based on *Goodbye to Berlin,* the British writer Christopher Isherwood’s collection of stories and character studies set in Weimar Germany as the Nazis are clawing their way to power. Isherwood, who went to Berlin for one reason—“boys,” he wrote in his memoir *Christopher and His Kind*—lived in a dingy boarding house amid an array of sleazy lodgers who inspired his characters. But aside from a fleeting mention of a host at a seedy nightclub, there is no emcee in his vignettes. Nor is there an emcee in *I Am a Camera,* John Van Druten’s hit 1951 Broadway play adapted from Isherwood’s story “Sally Bowles” from *Goodbye to Berlin.*

The character, one of the most famous in Broadway history, was created by [Harold Prince](https://archive.vanityfair.com/article/2016/1/hal-prince), who produced and directed the original *Cabaret.* “People write about *Cabaret* all the time,” says [John Kander](https://archive.vanityfair.com/article/2003/11/two-men-and-a-star), who composed the show’s music and is, at 96, the last living member of that creative team. “They write about Liza. They write about Joel, and sometimes about us \[Kander and lyricist Fred Ebb\]. None of that really matters. It’s all Hal. Everything about this piece, even the variations that happen in different versions of it, is all because of Hal.”

In 1964, Prince produced his biggest hit: *Fiddler on the Roof.* In the final scene, Tevye and his family, having survived a pogrom, leave for America. There is sadness but also hope. And what of the Jews who did not leave? *Cabaret* would provide the tragic answer.

But Prince was after something else. Without hitting the audience over the head, he wanted to create a musical that echoed what was happening in America: young men being sent to their deaths in Vietnam; racists such as Alabama politician “Bull” Connor siccing attack dogs on civil rights marchers. In rehearsals, Prince put up Will Counts’s iconic photograph of a white student screaming at a Black student during the Little Rock crisis of 1957. “That’s our show,” he told the cast.

A bold idea he had early on was to juxtapose the lives of Isherwood’s lodgers with one of the tawdry nightclubs Isherwood had frequented. In 1951, while stationed as a soldier in Stuttgart, Germany, Prince himself had hung around such a place. Presiding over the third-rate acts was a master of ceremonies in white makeup and of indeterminate sexuality. He “unnerved me,” Prince once told me. “But I never forgot him.”

Kander had seen the same kind of character at the opening of a [Marlene Dietrich](https://archive.vanityfair.com/article/1997/9/dietrich-lived-here) concert in Europe. “An overpainted little man waddled out and said, ‘*Willkommen, bienvenue,* welcome,’ ” Kander recalls.

The first song Kander and Ebb wrote for the show was called “Willkommen.” They wrote 60 more songs. “Some of them were outrageous,” Kander says. “We wrote some antisemitic songs”—of which there were many in Weimar cabarets—“‘Good neighbor Cohen, loaned you a loan.’ We didn’t get very far with that one.”

They did write one song *about* antisemitism: “If You Could See Her (The Gorilla Song),” in which the Emcee dances with his lover, a gorilla in a pink tutu. At the end of the number, he turns to the audience and whispers: “If you could see her through my eyes, she wouldn’t look Jewishhh at all.” It was, they thought, the most powerful song in the score.

The working title of their musical was *Welcome to Berlin.* But then a woman who sold blocks of tickets to theater parties told Prince that her Jewish clients would not buy a show with “Berlin” in the title. Strolling along the beach one day, Joe Masteroff, who was writing the musical’s book, thought of two recent hits, *Carnival* and *Camelot.* Both started with a *C* and had three syllables. Why not call the show *Cabaret*?

To play the Emcee, Prince tapped his friend Joel Grey. A nightclub headliner, Grey could not break into Broadway. “The theater was very high-minded,” he once said. When Prince called him, he was playing a pirate in a third-rate musical in New York’s Jones Beach. “Hal knew I was dying,” Grey recounts over lunch in the West Village, where he lives. “I wanted to quit the business.”

At first, he struggled to create the Emcee, who did not interact with the other characters. He had numbers but “no words, no lines, no role,” Grey wrote in his memoir, *Master of Ceremonies.* A polished performer, he had no trouble with the songs, the dances, the antics. “But something was missing,” he says. Then he remembered a cheap comedian he’d once seen in St. Louis. The comic had told lecherous jokes, gay jokes, sexist jokes—anything to get a laugh. One day in rehearsal, Grey did everything the comedian had done “to get the audience crazy. I was all over the girls, squeezing their breasts, touching their bottoms. They were furious. I was horrible. When it was over I thought, This is the end of my career.” He disappeared backstage and cried. “And then from out of the darkness came Mr. Prince,” Grey says. “He put his hand on my shoulder and said, ‘Joely, that’s it.’ ”

*C**abaret*** **played its** first performance at the Shubert Theatre in Boston in the fall of 1966. Grey stopped the show with the opening number, “Willkommen.” “The audience wouldn’t stop applauding,” Grey recalls. “I turned to the stage manager and said, ‘Should I get changed for the next scene?’ ”

The musical ran long—it was in three acts—but it got a prolonged standing ovation. As the curtain came down, Richard Seff, an agent who represented Kander and Ebb, ran into Ebb in the aisle. “It’s wonderful,” Seff said. “You’ll fix the obvious flaws.” In the middle of the night, Seff’s phone rang. It was Ebb. “You hated it!” the songwriter screamed. “You are of no help at all!”

Ebb was reeling because he’d learned Prince was going to cut the show down to two acts. Ebb collapsed in his hotel bed, Kander holding one hand, Grey the other. “You’re not dying, Fred,” Kander told him. “Hal has not wrecked our show.”

*Cabaret* came roaring into New York, fueled by tremendous word of mouth. But there was a problem. Some Jewish groups were furious about “If You Could See Her.” How could you equate a gorilla with a Jew? they wanted to know, missing the point entirely. They threatened to boycott the show. Prince, his eye on ticket sales, told Ebb to change the line “She wouldn’t look Jewish at all” to something less offensive: “She isn’t a *meeskite* at all,” using the Yiddish word for a homely person.

It is difficult to imagine the impact *Cabaret* had on audiences in 1966. World War II had ended only 21 years before. Many New York theatergoers had fled Europe or fought the Nazis. There were Holocaust survivors in the audience; there were people whose relatives had died in the gas chambers. Grey knew the show’s power. Some nights, dancing with the gorilla, he’d whisper “Jewish” instead of “meeskite.” The audience gasped.

*Cabaret* won eight Tony Awards in 1967, catapulted Grey to Broadway stardom, and ran for three years. Seff sold the movie rights for $1.5 million, a record at the time. Prince, about to begin rehearsals for Stephen Sondheim’s *Company,* was unavailable to direct the movie, scheduled for a 1972 release. So the producers hired the director and choreographer [Bob Fosse](https://www.vanityfair.com/culture/2013/11/bob-fosse-biography-review), who needed the job because his previous movie, *Sweet Charity,* had been a bust.

Fosse, who saw Prince as a rival, stamped out much of what Prince had done, including Joel Grey. He wanted Ruth Gordon to play the Emcee. But Grey was a sensation, and the studio wanted him. “It’s either me or Joel,” Fosse said. When the studio opted for Grey, Fosse backed down. But he resented Grey, and relations between them were icy.

A 26-year-old [Liza Minnelli](https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2002/03/happyvalley200203), on the way to stardom herself, was cast as Sally Bowles. The handsome Michael York would play the Cliff character, whose name in the movie was changed to Brian Roberts. And supermodel [Marisa Berenson](https://www.vogue.com/article/marisa-berenson-a-life-in-pictures) (who at the time seemed to be on the cover of *Vogue* every other month) got the role of a Jewish department store heiress, a character Fosse took from Isherwood’s short story “The Landauers.”

*Cabaret* was shot on location in Munich and Berlin. “The atmosphere was extremely heavy,” Berenson recalls. “There was the whole Nazi period, and I felt very much the Berlin Wall, that darkness, that fear, all that repression.” She adored Fosse, but he kept her off balance (she was playing a young woman traumatized by what was happening around her) by whispering “obscene things in my ear. He was shaking me up.”

Minnelli, costumed by Halston for the film, found Fosse “brilliant” and “incredibly intense,” she tells *Vanity Fair* in a rare interview. “He used every part of me, including my scoliosis. One of my great lessons in working with Fosse was never to think that whatever he was asking couldn’t be done. If he said do it, you had to figure out how to do it. You didn’t think about how much it hurt. You just made it happen.”

Back in New York, Fosse arranged a private screening of *Cabaret* for Kander and Ebb. When it was over, they said nothing. “We really hated it,” Kander admits. Then they went to the opening at the Ziegfeld Theatre in New York. The audience loved it. “We realized it was a masterpiece,” Kander says, laughing. “It just wasn’t our show.”

The success of the movie—with its eight Academy Awards—soon overshadowed the musical. When people thought of *Cabaret,* they thought of finger snaps and bowler hats. They thought of Fosse and, of course, Minnelli, who would adopt the lyric “Life is a cabaret” as her signature. Her best-actress Oscar became part of a dynasty: Her mother, [Judy Garland](https://archive.vanityfair.com/article/2000/4/till-mgm-do-us-part), and father, director [Vincente Minnelli](https://archive.vanityfair.com/article/2000/4/till-mgm-do-us-part), each had one of their own. “Papa was even more excited about the Oscar than I was,” she says. “And, baby, I was—no, I *am* still—excited.”

By 1987—in part to burnish *Cabaret*’s theatrical legacy—Prince decided to recreate his original production on Broadway, with Grey once again serving as the Emcee. But it had the odor of mothballs. The *New York Times* drama critic Frank Rich wrote that it was not, as Sally Bowles sings, “perfectly marvelous,” but “it does approach the perfectly mediocre.” Much of the show, he added, was “old-fashioned and plodding.”

I**n the early 1990s,** [Sam Mendes](https://www.vanityfair.com/style/2014/03/sam-mendes-rules-for-directors), then a young director running a pocket-size theater in London called the Donmar Warehouse, heard [the novelist Martin Amis](https://www.vanityfair.com/style/2023/05/martin-amis-is-dead-at-73) give a talk. Amis was writing *Time’s Arrow,* about a German doctor who works in a concentration camp. “I’ve already written about the Nazis and people say to me, ‘Why are you doing it again?’ ” Amis said. “And I say, what else is there?”

“At the end of the day,” Mendes tells me, “the biggest question of the 20th century is, ‘How could this have happened?’ ” Mendes decided to stage *Cabaret* at the Donmar in 1993. Another horror was unfolding at the time: Serb paramilitaries were slaughtering Bosnian Muslims, “ethnic cleansing” on an unimaginable scale.

Mendes hit on a terrific concept for his production: He transformed his theater into a nightclub. The audience sat at little tables with red lamps. And the performers were truly seedy. He told the actors playing the Kit Kat Club girls not to shave their armpits or their legs. “Unshaved armpits—it sent shock waves around the theater,” he recalls. Since there was no room—or money—for an orchestra, the actors played the instruments. Some of them could hit the right notes.

To play the Emcee, Mendes cast [Alan Cumming](https://archive.vanityfair.com/article/2014/4/alan-cumming), a young Scottish actor whose comedy act Mendes had enjoyed. “Can you sing?” Mendes asked him. “Yeah,” Cumming said. Mendes threw ideas at him and “he was open to everything.” Just before the first preview, Mendes suggested he come out during the intermission and chat up the audience, maybe dance with a woman. Mendes, frantic before the preview, never got around to giving Cumming any more direction than that. No matter. Cumming sauntered onstage as people were settling back at their tables, picked a man out of the crowd, and started dancing with him. “Watch your hands,” he said. “I lead.”