"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Fake Fake-News Problem and the Truth About Misinformation.md\"> The Fake Fake-News Problem and the Truth About Misinformation </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/A racial slur and a Fort Myers High baseball team torn apart - ESPN.md\"> A racial slur and a Fort Myers High baseball team torn apart - ESPN </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Riding the baddest bulls made him a legend. Then one broke his neck..md\"> Riding the baddest bulls made him a legend. Then one broke his neck. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Family Photographs That Helped Us Investigate How a University Displaced a Black Community.md\"> The Family Photographs That Helped Us Investigate How a University Displaced a Black Community </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Dark Matter Hazlitt.md\"> Dark Matter Hazlitt </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Frank Carone on Eric Adams’s Smash-and-Grab New York.md\"> Frank Carone on Eric Adams’s Smash-and-Grab New York </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Behind the New Iron Curtain, by Marzio G. Mian, Translated by Elettra Pauletto.md\"> Behind the New Iron Curtain, by Marzio G. Mian, Translated by Elettra Pauletto </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Can a Film Star Be Too Good-Looking.md\"> Can a Film Star Be Too Good-Looking </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/How climate change is turning camels into the new cows.md\"> How climate change is turning camels into the new cows </a>",

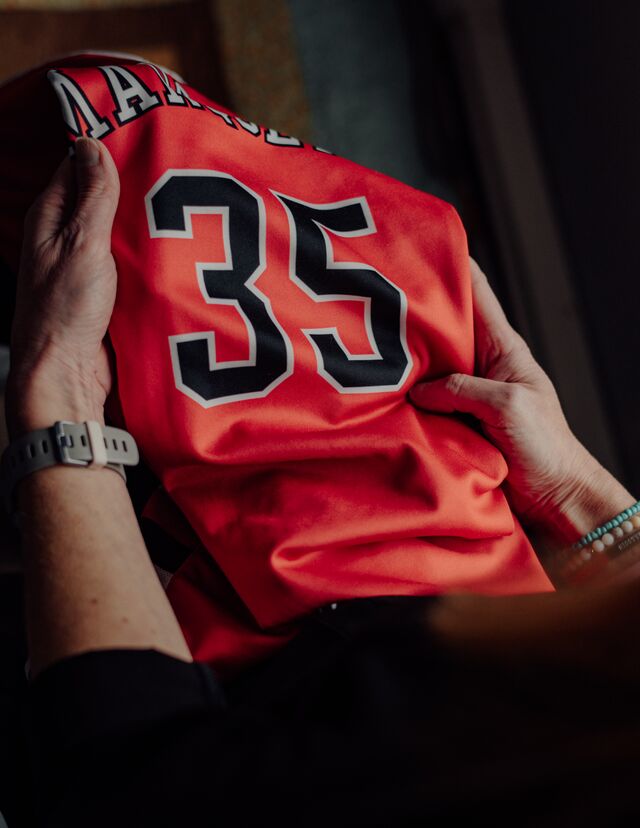

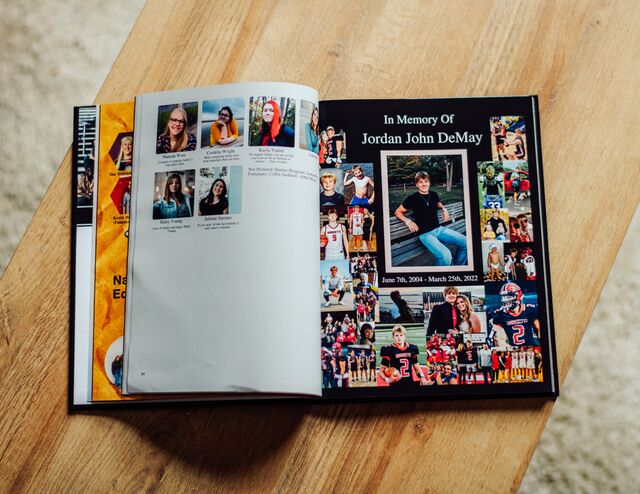

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Sextortion Scams Are Driving Teen Boys to Suicide.md\"> Sextortion Scams Are Driving Teen Boys to Suicide </a>",

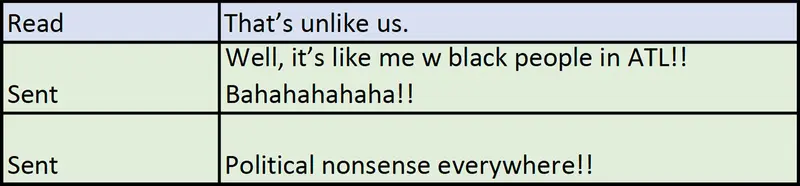

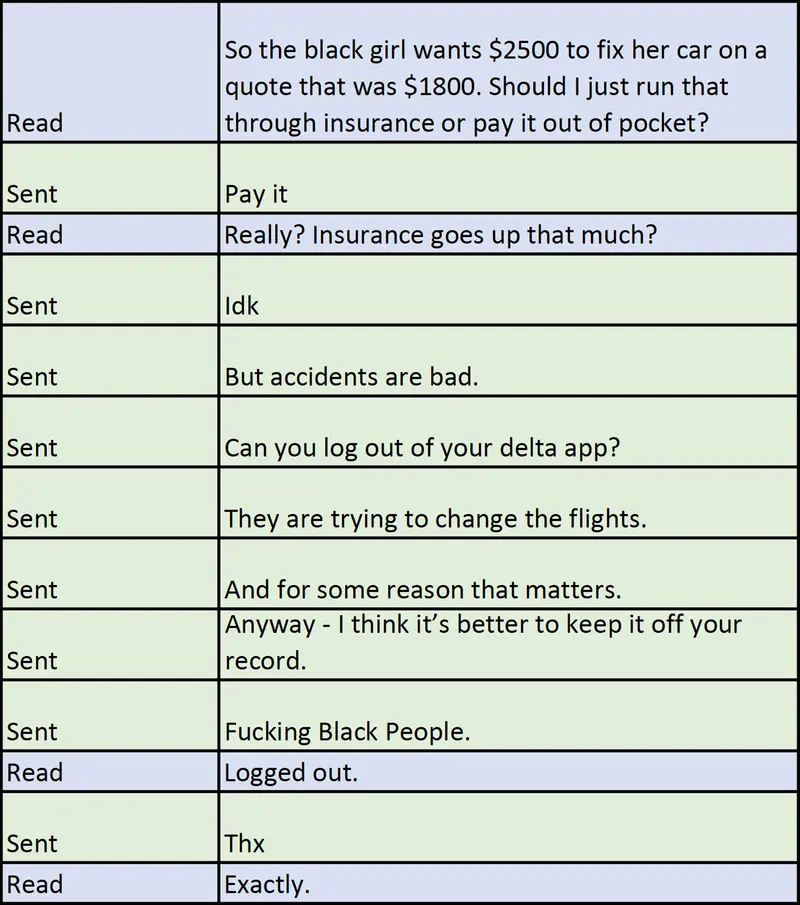

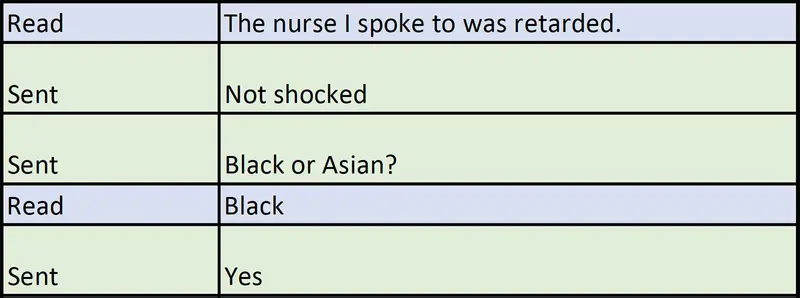

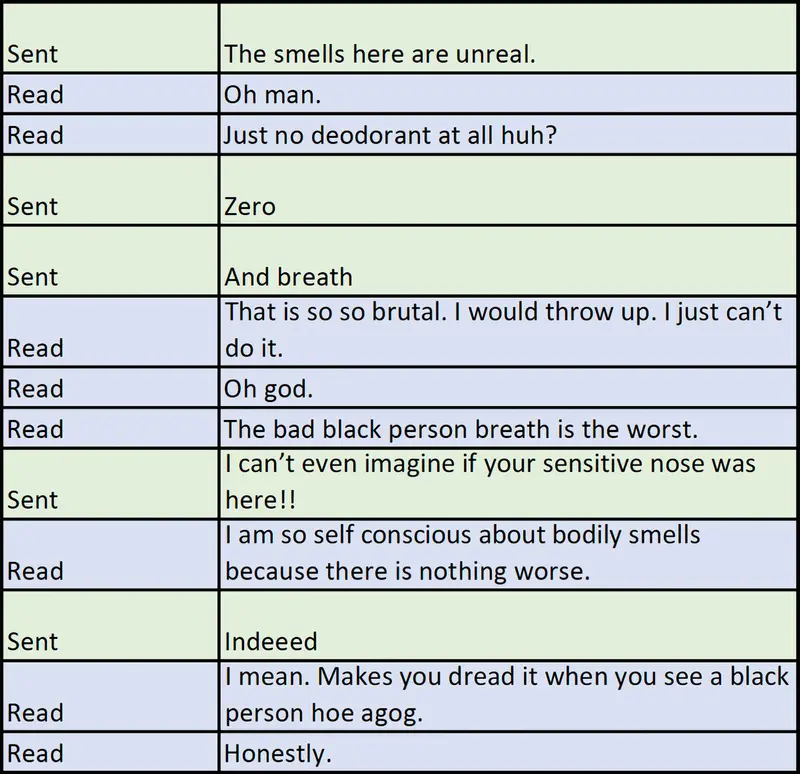

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/An Atlanta Movie Exec Praised for His Diversity Efforts Sent Racist, Antisemitic Texts.md\"> An Atlanta Movie Exec Praised for His Diversity Efforts Sent Racist, Antisemitic Texts </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/An Atlanta Movie Exec Praised for His Diversity Efforts Sent Racist, Antisemitic Texts.md\"> An Atlanta Movie Exec Praised for His Diversity Efforts Sent Racist, Antisemitic Texts </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/I Got Mailers Promoting Toddler Milk for My Children. I Went on to Investigate International Formula Marketing..md\"> I Got Mailers Promoting Toddler Milk for My Children. I Went on to Investigate International Formula Marketing. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Chinese Organized Crime’s Latest U.S. Target Gift Cards.md\"> Chinese Organized Crime’s Latest U.S. Target Gift Cards </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Butterfly in the Prison Yard.md\"> The Butterfly in the Prison Yard </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Great Serengeti Land Grab.md\"> The Great Serengeti Land Grab </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Vital City Jimmy Breslin and the Lost Rhythm of New York.md\"> Vital City Jimmy Breslin and the Lost Rhythm of New York </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The last days of Boston Market.md\"> The last days of Boston Market </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The soft life why millennials are quitting the rat race.md\"> The soft life why millennials are quitting the rat race </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Welcome to Northwestern University at Stateville.md\"> Welcome to Northwestern University at Stateville </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Cabaret’s Endurance Run The Untold History.md\"> Cabaret’s Endurance Run The Untold History </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/They came for Florida's sun and sand. They got soaring costs and a culture war..md\"> They came for Florida's sun and sand. They got soaring costs and a culture war. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/This is how reporters documented 1,000 deaths after police force that isn't supposed to be fatal.md\"> This is how reporters documented 1,000 deaths after police force that isn't supposed to be fatal </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Right-Wing Media and the Death of an Alabama Pastor An American Tragedy.md\"> Right-Wing Media and the Death of an Alabama Pastor An American Tragedy </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Who Is Podcast Guest Turned Star Andrew Huberman, Really.md\"> Who Is Podcast Guest Turned Star Andrew Huberman, Really </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/I have little time left. I hope my goodbye inspires you..md\"> I have little time left. I hope my goodbye inspires you. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/I am dying at age 49. Here’s why I have no regrets..md\"> I am dying at age 49. Here’s why I have no regrets. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/‘The whole bridge just fell down.’ The final minutes before the Key Bridge collapsed.md\"> ‘The whole bridge just fell down.’ The final minutes before the Key Bridge collapsed </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Evan Gershkovich’s Stolen Year in a Russian Jail.md\"> Evan Gershkovich’s Stolen Year in a Russian Jail </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/‘Yo Soy la Mamá’ A Migrant Mother’s Struggle to Get Back Her Son.md\"> ‘Yo Soy la Mamá’ A Migrant Mother’s Struggle to Get Back Her Son </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Masters of the Green The Black Caddies of Augusta National.md\"> Masters of the Green The Black Caddies of Augusta National </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Fake Fake-News Problem and the Truth About Misinformation.md\"> The Fake Fake-News Problem and the Truth About Misinformation </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/A racial slur and a Fort Myers High baseball team torn apart - ESPN.md\"> A racial slur and a Fort Myers High baseball team torn apart - ESPN </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Riding the baddest bulls made him a legend. Then one broke his neck..md\"> Riding the baddest bulls made him a legend. Then one broke his neck. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"01.07 Animals/2024-04-26 First S&B.md\"> 2024-04-26 First S&B </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Family Photographs That Helped Us Investigate How a University Displaced a Black Community.md\"> The Family Photographs That Helped Us Investigate How a University Displaced a Black Community </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.01 Admin/Calendars/Events/2024-04-21 ⚽️ PSG - OL (4-1).md\"> 2024-04-21 ⚽️ PSG - OL (4-1) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Dark Matter Hazlitt.md\"> Dark Matter Hazlitt </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Frank Carone on Eric Adams’s Smash-and-Grab New York.md\"> Frank Carone on Eric Adams’s Smash-and-Grab New York </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Behind the New Iron Curtain, by Marzio G. Mian, Translated by Elettra Pauletto.md\"> Behind the New Iron Curtain, by Marzio G. Mian, Translated by Elettra Pauletto </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Can a Film Star Be Too Good-Looking.md\"> Can a Film Star Be Too Good-Looking </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How climate change is turning camels into the new cows.md\"> How climate change is turning camels into the new cows </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Sextortion Scams Are Driving Teen Boys to Suicide.md\"> Sextortion Scams Are Driving Teen Boys to Suicide </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/An Atlanta Movie Exec Praised for His Diversity Efforts Sent Racist, Antisemitic Texts.md\"> An Atlanta Movie Exec Praised for His Diversity Efforts Sent Racist, Antisemitic Texts </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/I Got Mailers Promoting Toddler Milk for My Children. I Went on to Investigate International Formula Marketing..md\"> I Got Mailers Promoting Toddler Milk for My Children. I Went on to Investigate International Formula Marketing. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Chinese Organized Crime’s Latest U.S. Target Gift Cards.md\"> Chinese Organized Crime’s Latest U.S. Target Gift Cards </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.01 Reading list/Their Eyes Were Watching God.md\"> Their Eyes Were Watching God </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Butterfly in the Prison Yard.md\"> The Butterfly in the Prison Yard </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Great Serengeti Land Grab.md\"> The Great Serengeti Land Grab </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Vital City Jimmy Breslin and the Lost Rhythm of New York.md\"> Vital City Jimmy Breslin and the Lost Rhythm of New York </a>",

@ -12271,29 +12461,30 @@

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/I have little time left. I hope my goodbye inspires you..md\"> I have little time left. I hope my goodbye inspires you. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/I am dying at age 49. Here’s why I have no regrets..md\"> I am dying at age 49. Here’s why I have no regrets. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/‘The whole bridge just fell down.’ The final minutes before the Key Bridge collapsed.md\"> ‘The whole bridge just fell down.’ The final minutes before the Key Bridge collapsed </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Evan Gershkovich’s Stolen Year in a Russian Jail.md\"> Evan Gershkovich’s Stolen Year in a Russian Jail </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Masters of the Green The Black Caddies of Augusta National.md\"> Masters of the Green The Black Caddies of Augusta National </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Great American Novels.md\"> The Great American Novels </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/‘We wanted to invade media’ the hippies, nerds and Hollywood pros who brought The Simpsons to life.md\"> ‘We wanted to invade media’ the hippies, nerds and Hollywood pros who brought The Simpsons to life </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Inside the Glorious Afterlife of Roger Federer.md\"> Inside the Glorious Afterlife of Roger Federer </a>"

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Evan Gershkovich’s Stolen Year in a Russian Jail.md\"> Evan Gershkovich’s Stolen Year in a Russian Jail </a>"

],

"Tagged":[

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Fake Fake-News Problem and the Truth About Misinformation.md\"> The Fake Fake-News Problem and the Truth About Misinformation </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Riding the baddest bulls made him a legend. Then one broke his neck..md\"> Riding the baddest bulls made him a legend. Then one broke his neck. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/A racial slur and a Fort Myers High baseball team torn apart - ESPN.md\"> A racial slur and a Fort Myers High baseball team torn apart - ESPN </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"01.07 Animals/2024-04-26 First S&B.md\"> 2024-04-26 First S&B </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/2024-04-26 First S&B.md\"> 2024-04-26 First S&B </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Family Photographs That Helped Us Investigate How a University Displaced a Black Community.md\"> The Family Photographs That Helped Us Investigate How a University Displaced a Black Community </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Frank Carone on Eric Adams’s Smash-and-Grab New York.md\"> Frank Carone on Eric Adams’s Smash-and-Grab New York </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Dark Matter Hazlitt.md\"> Dark Matter Hazlitt </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Frank Carone on Eric Adams’s Smash-and-Grab New York.md\"> Frank Carone on Eric Adams’s Smash-and-Grab New York </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Can a Film Star Be Too Good-Looking.md\"> Can a Film Star Be Too Good-Looking </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Behind the New Iron Curtain, by Marzio G. Mian, Translated by Elettra Pauletto.md\"> Behind the New Iron Curtain, by Marzio G. Mian, Translated by Elettra Pauletto </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Sextortion Scams Are Driving Teen Boys to Suicide.md\"> Sextortion Scams Are Driving Teen Boys to Suicide </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How climate change is turning camels into the new cows.md\"> How climate change is turning camels into the new cows </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Butterfly in the Prison Yard.md\"> The Butterfly in the Prison Yard </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/I am dying at age 49. Here’s why I have no regrets..md\"> I am dying at age 49. Here’s why I have no regrets. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Chinese Organized Crime’s Latest U.S. Target Gift Cards.md\"> Chinese Organized Crime’s Latest U.S. Target Gift Cards </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/I Got Mailers Promoting Toddler Milk for My Children. I Went on to Investigate International Formula Marketing..md\"> I Got Mailers Promoting Toddler Milk for My Children. I Went on to Investigate International Formula Marketing. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Butterfly in the Prison Yard.md\"> The Butterfly in the Prison Yard </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The “Multi-Multi-Multi-Million-Dollar” Art Fraud That Shook the World.md\"> The “Multi-Multi-Multi-Million-Dollar” Art Fraud That Shook the World </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Vital City Jimmy Breslin and the Lost Rhythm of New York.md\"> Vital City Jimmy Breslin and the Lost Rhythm of New York </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.02 Travels/Skiing in Switzerland.md\"> Skiing in Switzerland </a>"

],

"Deleted":[

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Evan Gershkovich’s Stolen Year in a Russian Jail.md\"> Evan Gershkovich’s Stolen Year in a Russian Jail </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/An Atlanta Movie Exec Praised for His Diversity Efforts Sent Racist, Antisemitic Texts.md\"> An Atlanta Movie Exec Praised for His Diversity Efforts Sent Racist, Antisemitic Texts </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/How a Case Against Fox News Tore Apart a Media-Fighting Law Firm.md\"> How a Case Against Fox News Tore Apart a Media-Fighting Law Firm </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/‘Yo Soy la Mamá’ A Migrant Mother’s Struggle to Get Back Her Son.md\"> ‘Yo Soy la Mamá’ A Migrant Mother’s Struggle to Get Back Her Son </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/10 More Disturbing Revelations About Sam Bankman-Fried.md\"> 10 More Disturbing Revelations About Sam Bankman-Fried </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/These three brothers scammed their investors out of $233 million. Then they lived like kings.md\"> These three brothers scammed their investors out of $233 million. Then they lived like kings </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Meet the World's Top 'Chess Detective'.md\"> Meet the World's Top 'Chess Detective' </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Bad Faith at Second Mesa.md\"> Bad Faith at Second Mesa </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How the Record Industry Ruthlessly Punished Milli Vanilli for Anticipating the Future of Music.md\"> How the Record Industry Ruthlessly Punished Milli Vanilli for Anticipating the Future of Music </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Bad Faith at Second Mesa.md\"> Bad Faith at Second Mesa </a>"

],

"Linked":[

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Butterfly in the Prison Yard.md\"> The Butterfly in the Prison Yard </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The “Multi-Multi-Multi-Million-Dollar” Art Fraud That Shook the World.md\"> The “Multi-Multi-Multi-Million-Dollar” Art Fraud That Shook the World </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Vital City Jimmy Breslin and the Lost Rhythm of New York.md\"> Vital City Jimmy Breslin and the Lost Rhythm of New York </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Great Serengeti Land Grab.md\"> The Great Serengeti Land Grab </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Fake Fake-News Problem and the Truth About Misinformation.md\"> The Fake Fake-News Problem and the Truth About Misinformation </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Riding the baddest bulls made him a legend. Then one broke his neck..md\"> Riding the baddest bulls made him a legend. Then one broke his neck. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/A racial slur and a Fort Myers High baseball team torn apart - ESPN.md\"> A racial slur and a Fort Myers High baseball team torn apart - ESPN </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Right-Wing Media and the Death of an Alabama Pastor An American Tragedy.md\"> Right-Wing Media and the Death of an Alabama Pastor An American Tragedy </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/A Family’s Disappearance Rocked New Zealand. What Came After Has Stunned Everyone..md\"> A Family’s Disappearance Rocked New Zealand. What Came After Has Stunned Everyone. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Russia, Ukraine, and the Coming Schism in Orthodox Christianity.md\"> Russia, Ukraine, and the Coming Schism in Orthodox Christianity </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.05 Vinyls/Exile on Main St (by The Rolling Stones - 1972).md\"> Exile on Main St (by The Rolling Stones - 1972) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"01.07 Animals/2024-04-11 First exercice.md\"> 2024-04-11 First exercice </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The soft life why millennials are quitting the rat race.md\"> The soft life why millennials are quitting the rat race </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The last days of Boston Market.md\"> The last days of Boston Market </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Welcome to Northwestern University at Stateville.md\"> Welcome to Northwestern University at Stateville </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/This is how reporters documented 1,000 deaths after police force that isn't supposed to be fatal.md\"> This is how reporters documented 1,000 deaths after police force that isn't supposed to be fatal </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/They came for Florida's sun and sand. They got soaring costs and a culture war..md\"> They came for Florida's sun and sand. They got soaring costs and a culture war. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Family Photographs That Helped Us Investigate How a University Displaced a Black Community.md\"> The Family Photographs That Helped Us Investigate How a University Displaced a Black Community </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Welcome to Northwestern University at Stateville.md\"> Welcome to Northwestern University at Stateville </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Masters of the Green The Black Caddies of Augusta National.md\"> Masters of the Green The Black Caddies of Augusta National </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/I Got Mailers Promoting Toddler Milk for My Children. I Went on to Investigate International Formula Marketing..md\"> I Got Mailers Promoting Toddler Milk for My Children. I Went on to Investigate International Formula Marketing. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Sextortion Scams Are Driving Teen Boys to Suicide.md\"> Sextortion Scams Are Driving Teen Boys to Suicide </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Dark Matter Hazlitt.md\"> Dark Matter Hazlitt </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Cabaret’s Endurance Run The Untold History.md\"> Cabaret’s Endurance Run The Untold History </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/This is how reporters documented 1,000 deaths after police force that isn't supposed to be fatal.md\"> This is how reporters documented 1,000 deaths after police force that isn't supposed to be fatal </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Dark Matter Hazlitt.md\"> Dark Matter Hazlitt </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Frank Carone on Eric Adams’s Smash-and-Grab New York.md\"> Frank Carone on Eric Adams’s Smash-and-Grab New York </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Behind the New Iron Curtain, by Marzio G. Mian, Translated by Elettra Pauletto.md\"> Behind the New Iron Curtain, by Marzio G. Mian, Translated by Elettra Pauletto </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Can a Film Star Be Too Good-Looking.md\"> Can a Film Star Be Too Good-Looking </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Sextortion Scams Are Driving Teen Boys to Suicide.md\"> Sextortion Scams Are Driving Teen Boys to Suicide </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How climate change is turning camels into the new cows.md\"> How climate change is turning camels into the new cows </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Butterfly in the Prison Yard.md\"> The Butterfly in the Prison Yard </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Russia, Ukraine, and the Coming Schism in Orthodox Christianity.md\"> Russia, Ukraine, and the Coming Schism in Orthodox Christianity </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Who Is Podcast Guest Turned Star Andrew Huberman, Really.md\"> Who Is Podcast Guest Turned Star Andrew Huberman, Really </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Right-Wing Media and the Death of an Alabama Pastor An American Tragedy.md\"> Right-Wing Media and the Death of an Alabama Pastor An American Tragedy </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/‘The whole bridge just fell down.’ The final minutes before the Key Bridge collapsed.md\"> ‘The whole bridge just fell down.’ The final minutes before the Key Bridge collapsed </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/They came for Florida's sun and sand. They got soaring costs and a culture war..md\"> They came for Florida's sun and sand. They got soaring costs and a culture war. </a>"

],

"Removed Tags from":[

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Right-Wing Media and the Death of an Alabama Pastor An American Tragedy.md\"> Right-Wing Media and the Death of an Alabama Pastor An American Tragedy </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Sextortion Scams Are Driving Teen Boys to Suicide.md\"> Sextortion Scams Are Driving Teen Boys to Suicide </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Who Is Podcast Guest Turned Star Andrew Huberman, Really.md\"> Who Is Podcast Guest Turned Star Andrew Huberman, Really </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/I am dying at age 49. Here’s why I have no regrets..md\"> I am dying at age 49. Here’s why I have no regrets. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.01 Reading list/On the Road.md\"> On the Road </a>"

],

"Removed Links from":[

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/I am dying at age 49. Here’s why I have no regrets..md\"> I am dying at age 49. Here’s why I have no regrets. </a>",

"title":":heavy_dollar_sign: [[@Finances|Finances]]: update crypto prices within Obsidian %%done_del%%",

"time":"2024-05-14",

"rowNumber":116

},

{

"title":":moneybag: [[@Finances]]: Transfer UK pension to CH %%done_del%%",

"time":"2024-10-31",

@ -420,11 +415,6 @@

}

],

"01.01 Life Orga/@Personal projects.md":[

{

"title":":fork_and_knife: [[@Personal projects|Personal projects]]: Rechercher à créer un set Christofle (80e les 6 couteaux; 120e les 6 autres aux Puces)",

"time":"2024-05-30",

"rowNumber":75

},

{

"title":":art: [[@Personal projects|Personal projects]]: Continuer à construire un petit trousseau d'[[@Personal projects#art|art]]",

"time":"2024-06-21",

@ -440,6 +430,11 @@

"time":"2024-06-30",

"rowNumber":78

},

{

"title":":fork_and_knife: [[@Personal projects|Personal projects]]: Rechercher à créer un set Christofle (80e les 6 couteaux; 120e les 6 autres aux Puces)",

"title":":hibiscus: :fork_and_knife: [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Book a restaurant with terrace for the season: [[Albishaus]], [[Restaurant Boldern]], [[Zur Buech]], [[Jardin Zürichberg]], [[Bistro Rigiblick]], [[Portofino am See]], [[La Réserve|La Muña]] %%done_del%%",

"time":"2024-05-01",

"rowNumber":104

},

{

"title":"🎭:frame_with_picture: [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Check out exhibitions at the [Kunsthaus](https://www.kunsthaus.ch/en/) %%done_del%%",

"time":"2024-05-15",

@ -831,7 +809,7 @@

{

"title":":hibiscus: :canned_food: [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Check out [FOOD ZURICH - MEHR ALS EIN FESTIVAL](https://www.foodzurich.com/de/) %%done_del%%",

"time":"2024-06-01",

"rowNumber":105

"rowNumber":106

},

{

"title":"🎭:frame_with_picture: [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Check out exhibitions at the [Rietberg](https://rietberg.ch/en/) %%done_del%%",

@ -841,42 +819,42 @@

{

"title":":hibiscus: :partying_face: [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Zürich Pride Festival %%done_del%%",

"time":"2024-06-15",

"rowNumber":120

"rowNumber":121

},

{

"title":":sunny: :movie_camera: [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Check out programmation of the [Zurich's finest open-air cinema | Allianz Cinema -](https://zuerich.allianzcinema.ch/en) %%done_del%%",

"time":"2024-07-01",

"rowNumber":106

"rowNumber":107

},

{

"title":":sunny: :partying_face: [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Check out Seenachtfest Rapperswil-Jona %%done_del%%",

"time":"2024-08-01",

"rowNumber":123

"rowNumber":124

},

{

"title":":sunny: :runner: [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Check out tickets to Weltklasse Zürich %%done_del%%",

"time":"2024-08-01",

"rowNumber":130

"rowNumber":132

},

{

"title":":sunny: :partying_face: [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Street Parade %%done_del%%",

"title":":maple_leaf: :movie_camera: [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Check out Zürich Film Festival %%done_del%%",

"time":"2024-09-15",

"rowNumber":107

"rowNumber":108

},

{

"title":":maple_leaf: :wine_glass: [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Check out Zürich’s Wine festival ([ZWF - Zurich Wine Festival](https://zurichwinefestival.ch/)) %%done_del%%",

"time":"2024-09-25",

"rowNumber":108

"rowNumber":109

},

{

"title":":snowflake:🎭 [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Check out floating theatre ([Herzlich willkommen!](http://herzbaracke.ch/)) %%done_del%%",

@ -886,7 +864,7 @@

{

"title":":maple_leaf: :wine_glass: [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Check out [Discover the Excitement of EXPOVINA Wine Events | Join Us at Weinschiffe, Primavera, and Wine Trophy | EXPOVINA](https://expovina.ch/en-ch/) %%done_del%%",

"time":"2024-10-15",

"rowNumber":109

"rowNumber":110

},

{

"title":":snowflake: :person_in_steamy_room: [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Check out [Sauna Cubes at Strandbad Küsnacht — Strandbadsauna](https://www.strandbadsauna.ch/home-eng) %%done_del%%",

"title":":hibiscus: :fork_and_knife: [[@@Zürich|:test_zurich_coat_of_arms:]]: Book a restaurant with terrace for the season: [[Albishaus]], [[Restaurant Boldern]], [[Zur Buech]], [[Jardin Zürichberg]], [[Bistro Rigiblick]], [[Portofino am See]], [[La Réserve|La Muña]] %%done_del%%",

"time":"2025-05-01",

"rowNumber":104

}

],

"03.02 Travels/Geneva.md":[

@ -952,17 +940,10 @@

"rowNumber":129

}

],

"00.01 Admin/Calendars/2024-01-22.md":[

{

"title":"16:06 :ski: [[@Lifestyle|Lifestyle]]: Look for a ski bag & a ski boot bag",

"time":"2024-04-15",

"rowNumber":104

}

],

"01.08 Garden/@Plants.md":[

{

"title":":potted_plant: [[@Plants|Plants]]: Buy fertilizer for the season %%done_del%%",

"time":"2024-04-30",

"time":"2024-05-31",

"rowNumber":111

}

],

@ -1007,18 +988,45 @@

"rowNumber":107

}

],

"00.01 Admin/Calendars/2024-03-15.md":[

"01.03 Family/Dorothée Moulin.md":[

{

"title":"09:15 :performing_arts: [[@Lifestyle|Lifestyle]]: Book tickets for the [Colombian exhibition]([](https://rietberg.ch/en/exhibitions/morethangold)) at the Rietberg",

- [] 09:15 :performing_arts: [[@Lifestyle|Lifestyle]]: Book tickets for the [Colombian exhibition]([](https://rietberg.ch/en/exhibitions/morethangold)) at the Rietberg 📅 2024-04-01

- [x] 09:15 :performing_arts: [[@Lifestyle|Lifestyle]]: Book tickets for the [Colombian exhibition]([](https://rietberg.ch/en/exhibitions/morethangold)) at the Rietberg 📅 2024-04-01 ✅ 2024-04-20

# A racial slur and a Fort Myers High baseball team torn apart - ESPN

*This story has been corrected. Read below*

## ACT I: ERUPTION

**ON APRIL 6, 2023,** at Terry Park in Fort Myers, Florida, the Fort Myers High Green Wave and Estero Wildcats met as part of the annual Battle of the Border, the in-season tournament between Lee County high school baseball teams.

Tate Reilly batted leadoff that day. The Fort Myers senior outfielder was surprised by the plum assignment. He had been on the varsity two seasons and batted in the bottom third of the order. Leading off should have buttressed the even better news he held in his heart: He received an offer to play at Albertus Magnus College, a Division III school in New Haven, Connecticut. He would soon be a college player, and receiving a firm scholarship represented a vindication of the hard work he'd put into a difficult game.

Madrid Tucker was to bat second. Tucker's father is Michael Tucker, who was the 10th overall pick by theKansas City Royalsin the 1992 draft. Tucker played for seven teams over a 12-year big league career, appearing in the National League Championship Series three times. Just a sophomore, Madrid played varsity as a freshman and already had been offered a dozen scholarships to play baseball, some at Power 5 schools. Six-foot tall and widely considered by his coaches to be the most promising player on the team, Madrid Tucker played in the prestigious Hank Aaron Invitational, the joint MLB/Players Association tournament in Vero Beach, Florida, designed to develop and increase the shrinking number of Black players in the majors. He was a high-level prospect, a three-sport star on a trajectory for Division I or the Major League amateur draft by the time he graduates. According to one national prep tracking service, in 2023 he was ranked second at shortstop in talent-rich Florida and 75th overall in the nation.

While Madrid stood in the on-deck circle taking practice cuts, Reilly saw two pitches. On the second, Robert Hinson, the Fort Myers third-base coach -- his coach -- walked off the field. Seconds later, two more coaches and at least nine Fort Myers players followed out of the dugout. One player walking off the field said, "I'm out," to which Hinson added, "I'm out of here."

As the players headed for the parking lot, chaos ensued. According to later testimony, some parents and fans in the bleachers "began applauding, cheering and fist-bumping the players walking out." One Fort Myers administrator who witnessed the walkout and ensuing cheering called the scene "so selfish ... an injustice to the kids." She would later tell investigators, "This is just sickening."

In the parking lot, adults traded insults. John Dailey, a hulking man identified in one video, approached Tate Reilly's mother, Melanie, and told her, "I'm going to pray for the evil in your heart to go away." Police arrived. As various onlookers began taking cellphone video, the sound of metal baseball cleats crunching against the pavement best told the story: Led by their adult coaches and supported by their parents, members of the Fort Myers high school baseball team quit a game and left their two teammates, Reilly and Tucker, who happened to be the only two players of color on the team, alone on the field.

Xavier Medina, an assistant coach for Estero, watched from across the diamond. In all his years coaching youth sports, he had never seen a team abandon its own players. As the bizarre scene unfolded, he was witnessing the antithesis of what sports were supposed to be about. The cliches of teamwork and togetherness were collapsing in real time. Players wearing the same uniform were not united against Estero. They were divided against themselves. His second conclusion was even worse: The walkout did not appear to be a reckless act concocted by teenagers, but rather orchestrated and blessed by coaches and parents. The kids were taking the lead from the grown-ups.

"In my mind, yes, the adults were behind it," Medina said. "If that were my team and we saw the players doing that, we would have immediately asked what they were doing and why. And we would have told them to go back to playing baseball. But here's why I don't think it was the players' idea: When they started walking off of the field, not a single adult, parent or coach, tried to stop them. Not one."

**THE WALKOUT RESULTED** in the cancellation of the remainder of the baseball season; multiple local and state investigations; the resignation, firing or reassignment of virtually every coach and school administrator involved with the incident; and two federal discrimination lawsuits, one filed in February by the Tucker family and another in early April by the Reillys. It was the product of simmering fractures within the Fort Myers baseball community that had been allowed to fester long before the first pitch of the season.

The avalanche of broken relationships within this baseball community at Fort Myers High -- a school considered the "crown jewel" of the Lee County high schools -- served as a microcosm for a polarized country: the small handful of Black players on both the junior varsity and varsity felt hostility within the baseball environment, and many of the white parents, whose children comprise an overwhelming majority at both levels, insisted it was they who have endured unfair treatment -- because they were white.

ESPN interviewed Fort Myers High parents, reviewed three completed school district investigation reports into the baseball team -- a state investigation is still pending -- along with hundreds of pages of school personnel records of coaches and administrators and bodycam footage from the Fort Myers Police Department, all acquired via Freedom of Information Act requests, as well as cellphone footage from the walkout. Before the Tucker and Reilly families filed their lawsuits, Rob Spicker, assistant director, media relations and public information for the school district of Lee County, declined all requests to be interviewed or to make any employee of the school district of Lee County -- administrators, or coaches -- available for comment. "Our comment is the report speaks for itself," Spicker told ESPN in September. Two active members of the Lee County School Board, Melisa Giovannelli and Jada Langford-Fleming, also declined to be interviewed. After the lawsuits were filed, Spicker declined subsequent interview requests from ESPN, citing ongoing litigation. John Dailey, one of the adults who encouraged the walkout, declined to comment when approached by ESPN in April. The parents of three players who participated in the walkout also declined to be interviewed by ESPN.

While many team issues fell under the common soap opera of high school sports -- a nationwide epidemic of meddling parents and overbearing coaches, the unending battle between fair participation and winning at all costs -- virtually the entirety of the grievances that destroyed the 2023 baseball team can be traced to two specific areas: the internecine racial history of Fort Myers, and, more urgently, the enforcement of conservative mandates playing out in education in Florida and around the nation.

The baseball team provided an explosive stage even before last season began. Untrusting of the overall competence and values of the coaching staff, one white player quit the team before the season started. Another Black player, unconvinced varsity head coach Kyle Burchfield would give him a fair chance to compete and wary of the racial attitudes of Burchfield's second-year assistant coach Alex Carcioppolo, chose not to try out at all.

Another parent would tell school district investigators that in 2022, a white player on the junior varsity said he "wanted to punch those two n-----s in the face," referring to two of his Black teammates. When some parents -- both white and Black -- complained first to Chris Chappell, the head junior varsity coach, and later to Burchfield, Burchfield told investigators he successfully handled the incident. Parental sources said otherwise, that the coaches left the wound undressed. One source said Carcioppolo told the players and their parents to "get over it." The N-word, he reportedly reasoned, was "just a word." Carcioppolo, the source concluded, was frustrated that an oversensitive country was just making everything worse. In January 2023, Michael Tucker says he and his wife, Dee, met with Burchfield to tell the coach they did not want Carcioppolo associating with their son. Burchfield, they say, did nothing.

By allowing issues to simmer, several people associated with the situation thought the coaches already had lost control of the team. "Had they dealt with it a year ago," one white parent said, "all the things that happened would have never happened."

**THE FIRST FRACTURE** of the season occurred Feb. 14, 2023, a week before Fort Myers' first game. Burchfield sent a routine message into the team group chat regarding upcoming scheduling, to which Carcioppolo responded, "Happy Valentines Day, n---as." The offensive message was either deleted "within seconds," or according to some players, several minutes before Carcioppolo responded, "Yikes," and deleted the text. Carcioppolo said the text was intended for a group of Black military friends and wound up mistakenly on the team group chat, an alibi some parents found flimsy. "If it was for them," Michael Tucker said, "why didn't any of his Black war buddies come to his defense?"

Carcioppolo was fired within 48 hours and, as mandated by state law, the school district opened a Title VI discrimination investigation, named after the section of the 1964 Civil Rights Act that prohibits discrimination in programs and activities receiving federal financial assistance. The viral text likely had been copied and shared dozens, perhaps hundreds, of times before Carcioppolo deleted it, but a certain conventional wisdom raced through the Fort Myers High baseball ecosystem: The Reillys and the Tuckers -- the only two families of color on the team -- had to be the ones who alerted school officials.

Carcioppolo's dismissal immediately was seen by many parents largely through the lens of race: White parents in his defense reasoned that a good man, an Afghan War veteran, Purple Heart recipient and a popular coach, had made an honest mistake and should be forgiven. Only the combination of "political correctness" and the racial pressure of appeasing the "troublemaker parent" pair of the interracial Reilly family and the African American Tuckers prevented Carcioppolo from receiving grace -- and an explosive issue from being quietly resolved by an apology and a second chance.

Furthermore, many white parents and players were enraged that a white coach was fired for using a word Black people used routinely as a figure of speech. It was an unfair racial double standard that galvanized the grievance of the white players and parents. In a group text chat that comprised only the team's seniors, some players argued if Carcioppolo were Black, no one would have cared.

Several players decided the best way to make themselves heard was to boycott the first game of the season in protest unless Carcioppolo was not immediately reinstated. The Tuckers and Reillys were stunned that an adult making a racial slur would be the issue around which the team would unify.

"They don't understand the magnitude within itself. You were going to boycott -- for *this?* That makes you racist," Dee Tucker said. "You don't fight to say Jewish slurs. You don't fight to say LGBTQ words. You don't fight for any other words, but you fight for this one. This one particular word is the one you're OK with because you think we're beneath you."

Burchfield would tell investigators that Carcioppolo's firing was the first time he had heard the word "walkout" around his team. Tate Reilly recalled being asked by his white teammates to join the movement. When he declined, alienation from his teammates ensued.

"It changed the course of the rest of the year compared to what we had in the fall," Tate Reilly recalled. "All of the friendships that we made were kinda on thin ice. All of the relationships with the coaches were on thin ice. It was who you wanted to walk on eggshells around. You didn't have a safe place unless you fit in with the herd. You had to go with what everyone else said, and if you weren't with them, then you were against them."

His isolation increased, he recalled, by his decision to sit in the cafeteria with teammate Madrid Tucker. "As soon as he didn't support boycotting for Carcioppolo, the players and the coaches targeted my son," said Tate's father, Shane. Added Dee Tucker: "Tate was part of the in-crowd until he refused to join the boycott for Coach Alex. Once he started sitting with Madrid, they went after him."

**CARCIOPPOLO'S FIRING IGNITED** a chain of smoldering racial resentments. Contentious school board meetings, simmering individual tensions between Burchfield and parents, Black and white. Angry white parents believed Carcioppolo's firing should have ended the controversy, but the Reillys and Tuckers refused to, as both families said they were told to "move on." Feeling silenced by the majority only deepened the chasm, Dee Tucker said.

The Green Wave also were losing -- Fort Myers lost its first seven games of the season -- but not all the losses could be attributed to racial turmoil; they were a young team. Still, race and cultural grievance permeated the dysfunction. Some white parents, community members and often Burchfield himself privately pointed to Madrid Tucker as the problem.

Carcioppolo was fired for using the N-word, they reasoned, but Black people used the word frequently and without penalty -- in routine speech and in popular music -- while a white coach had used it and was fired. The anger over use of the word at Fort Myers mirrored conversations and controversies around the country. The word was ubiquitous, and yet a white coach was now unemployed. On the baseball team, Tucker had been heard by several players and coaches using the N-word, just as Carcioppolo had, and they saw his use of the word without sanction an example of a double standard unfair to them. To angry parents, Tucker was proof of an America that punished only white people. A 2022 University of Maryland poll found that half of white Republicans saw "a lot more" discrimination against white Americans over the previous five years. That Tucker at the time was a 16-year-old sophomore and Carcioppolo was a 35-year-old coach did not assuage the collective anger of many parents.

On Feb. 23, nine days after Carcioppolo's text message, Burchfield held a meeting announcing tougher discipline. The following day, Burchfield emailed his zero-tolerance mandate to parents: "If a player strikes out and throws his hands up at the umpire and starts cussing, they will be removed from the game. No excuses. ... Actions will be taken that may look severe, but it is necessary to end the disrespect they have created for themselves, you as parents, our program, and the game of baseball." The email continued: "If any racial slurs are used at any point, the player will be removed from the game and suspended. ... Depending on the manner it was used it could be multiple game suspensions, it could be removal from the team."

Burchfield concluded his email with a tough love message delivered in all caps: "These steps taken by the coaching staff is FOR THE BOYS." The Tuckers interpreted the message as a vindictive response to Carcioppolo's firing, and now they felt Burchfield was pandering to white parents who claimed Madrid Tucker to be the beneficiary of "reverse racism" while Carcioppolo was a victim of "cancel culture." From the Tuckers' viewpoint, a moment adults could have used to constructively discuss racism was transformed into a weapon against their son.

Burchfield's tough-love message produced an unintended consequence: Instead of treating each other as teammates, players and parents began policing each other's behavior to coaches, each action or inaction proof of unfair double standards. Relations on the team grew so toxic that the school principal, Dr. Robert Butz, decided to place a school administrator in the Fort Myers dugout for every game.

Soon after, Tucker joked with a Black friend on the junior varsity, and while both were in the locker room laughing, Tucker at one point said, "N---a, pay attention." As the two Black kids continued conversing, some white players raced straight to their parents. The parents immediately went to Burchfield, who suspended Tucker for the first four innings of the next game. In another moment, Tucker threw his helmet to the ground during a three-strikeout game. Two teammates with whom Tucker was not particularly friendly engaged him to calm down -- but instead of support, Tucker saw their presence as goading. Words were exchanged. When a player suggested Tucker was all talk, he assured them he wasn't -- investigators reported Tucker told his teammate to "shut the f--- up or imma beat your ass" -- and his response netted him a five-game suspension.

The Tuckers were furious. A five-game suspension was disproportionate to the crime. Two Black kids talking to each other using common language did not constitute "hate speech." The Tuckers argued their son made no racial slur against another race -- he was talking to a friend, speaking the way people of the same race joke with one another. The sanction left the Tuckers with another conclusion: By attempting to suspend their son for 40% of the remaining season, Burchfield and the coaches were trying to make Madrid quit.

"The whole thing didn't make sense to me," Dee Tucker said. "Madrid used the word to another Black kid, and all the white kids ran and told the coach. The kid he said it to wasn't white. It wasn't like he called a white kid a cracker."

Michael Tucker began derisively calling Burchfield's new mandate "The Madrid Rules." In a charged private meeting with the Tuckers, Burchfield, athletic director Steven Cato and an assistant principal, Kelly Heinzman-Britton, Burchfield told the Tuckers that of all the players he'd ever coached, their son was "the worst" at handling his emotions. In the meeting, which Michael and Dee Tucker say they recorded with the room's knowledge and Cato's permission, Michael Tucker said to Burchfield, "No offense to you, Kyle, but how is it that we've been talking about racial issues, big bombshells being dropped for over six weeks, kids have been doing stuff, and the only kids that have been disciplined are the kids of color? How is that?" According to the recorded conversation, Burchfield did not respond to Tucker, nor did any administrator in the room.

Before the suspension was to go into effect, Burchfield was told by Butzthat district regulations against the appearance of retaliation prevented Madrid's suspension because the Carcioppolo investigation was not yet complete. That triggered more outrage from white parents: Madrid was receiving "preferential treatment" not because of an ongoing investigation, but because he was Black.

Trust between the Tuckers and Burchfield deteriorated. The Tuckers were once advocates of Burchfield. Four years earlier, they supported his hire. Michael Tucker attended Burchfield's wedding. Michael Tucker now saw Burchfield as duplicitous, assuring the family he was an ally, telling the Tuckers he understood the distinction between colloquial Black speech within the racial group while privately stoking the anger of white parents. Burchfield would confirm Michael Tucker's fear, later telling investigators that Madrid Tucker "dropped the N-word twice, with little to no consequences. It created a caustic environment showing the team there are no consequences to breaking the rules. The district tied my hands throughout the balance of the season."

Burchfield sanctioned Tucker in other ways: extra running, and twice sitting him for the early innings of games. Without a suspension, however, parents believed Madrid received no punishments, which led to players again discussing a boycott of the team.

Burchfield told investigators that on at least two occasions he had heard rumors of walkouts but nothing definite. Cato said the same, telling investigators walkout rumors had been discussed internally at the administrative level, with principal Butz, but no one confronted the players about the purpose of such a move or its consequences. Nor did Cato, Butz or anyone else who was aware of a possible walkout alert the Tucker family that some of Madrid's teammates were planning to target their child with a protest action.

"Do I feel like Fort Myers High School protected my son?" Michael Tucker asked. "No. No, I don't."

**MEANWHILE, SHANE REILLY** was convinced his son was being targeted by teammates, instigated by the coaches. A month before the walkout, Shane Reilly emailed Fernando Vazquez, a school district investigator, recommending Burchfield be fired as a coach and the "student(s) involved in the malicious targeting of my son to be kicked off the team." School documents contain several emails from Shane Reilly to school administrators demanding action. On April 8, 2023, Shane Reilly emailed Butz and told him he ordered Tate to "call 911 immediately" should he face any threat because "we have little confidence in Fort Myers High School's willingness to protect ALL kids."

There was nothing about Tate Reilly's senior year he would recall fondly. After he refused to support Carcioppolo, many of the white friends he believed he'd made on the baseball team were not friends at all. He increasingly believed Burchfield -- whom he'd known since he was 11 years old -- did not believe in him as a player. "I have nothing good to say about Coach Burchfield," he said.

Tate Reilly's instincts were correct. When his offer from Albertus Magnus was announced, Burchfield celebrated the senior publicly, but privately he held a dim view of Reilly's toughness and raw ability. "He is the slowest outfielder, he has the weakest arm, he's an OK hitter," Burchfield would later tell investigators. "He's going to play Division III baseball. There is no Division III baseball in Florida. A good high school team would beat a Division III school. I tried to help him with Division II schools. No school wanted him. I tried to help him with travel teams. No travel team wanted him." In a separate interview with investigators, Burchfield said he batted Tate Reilly low in the order "because of his speed. He's very slow. He doesn't have the best baseball IQ. When he's on base, he gets picked off. ... He gets signs wrong. It costs us wins."

Burchfield cut an imposing figure: about 6-foot-6, he headed travel teams and boasted his coaching bona fides -- the number of well-known MLB stars he'd played with, and the best calling card of them all: On his Facebook page and lesson sign-up sheets, he listed himself as a scout for theAtlanta Braves.

The Valentine's Day text was compounded by a series of incidents during the season. On April 4, at the apex of his frustration, Shane Reilly began filing what would become three separate complaints that would lead to Burchfield's suspension. One allegation stemmed from a March 10 game against Riverview High School in Sarasota. Burchfield was said to have forcibly redirected Tate Reilly toward the dugout by grabbing him between the neck and shoulder. Another alleged Hinson intentionally provided false information to the coaching staff, which led to Tate being benched.Reilly also alleged his son's baseball glove was stolen in retaliation for not supporting the aborted Carcioppolo boycott.

Shane Reilly's complaints led to Burchfield being investigated for physically confronting a student as well as the two other charges, but players and parents were given no explanation. Per district rules, a person who is the subject of an investigation is temporarily removed with pay from their position.

White players and coaches reached their boiling point. Days earlier, a Fort Myers parent, Krista Nowak Walsh, posted an article on social media from the People magazine website about Mississippi meteorologist Barbie Bassett, who was taken off the air at NBC affiliate WLBT for apparently quoting a Snoop Dogg lyric that translated into the N-word:

"OMG! But if it was the other way around, that person would still be on the air. Just like when a kid on a HS baseball team calls another teammate the N-word, that kid is still on the team, not suspended, etc...but my kid doesn't start because he cussed \[to himself in frustration\]. Can you guess who's white?"

Throughout the controversy, white parents believed the Tuckers and Reillys were the only voices being heard. In response to a social media post, Nowak Walsh said, "They're only listening to 1 of trouble maker family!"

**ON JUNE 4, 1940,** with Germany having already conquered the Netherlands, France and much of Western Europe, and five weeks from his nation being invaded by the Nazis, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill delivered his greatest oratory, the "We Shall Fight on the Beaches" speech. "We shall fight on the beaches. We shall fight on the landing grounds. We shall fight in the fields and in the streets. We shall fight in the hills. We shall never surrender," Churchill told the British House of Commons. His famous defiance was broadcast on radio throughout the United Kingdom and would symbolize what would become the resilient Allied effort in World War II.

More than 82 years later, in his November 2022 speech after sweeping to a second term as governor of Florida, Republican Ron DeSantis chose a similar cadence against a dissimilar enemy -- citizens of his own country and the teaching of multiculturalism. "We reject woke ideology. We fight the woke in the legislature. We fight the woke in the schools. We fight the woke in the corporations. We will never, ever surrender to the woke mob. Florida is where woke goes to die."

DeSantis repackaging of one of the world's darkest moments, and by extension conjuring a disturbing parallel between American citizens of different viewpoints and Nazi Germany, came with serious and disturbing implications. The southwest coast of Florida is heavily conservative and Republican, fertile ground for the divisions playing out across the country -- and on the Fort Myers baseball team. A 2021 Pew Research Center study of more than 10,000 adults found that more than half of white Americans do not believe being white provides them societal advantages. Ninety percent of Black Americans surveyed believed white people benefited "a fair amount" from being white.

In the 2016 election, Donald Trump won Lee County by 20 points over Hillary Clinton, and margins of victory of 27.6 and 25.7 points in bordering Charlotte and Collier counties, respectively. In 2020, Trump lost the general election but won Lee County by 19 points, Charlotte and Collier counties by 27 and 25 points, respectively.

In his two gubernatorial races, DeSantis defeated Andrew Gillum by 22 points in Lee County, and in 2022 crushed Democrat and former Florida governor Charlie Crist by nearly 40 points.

Within that mandate, Florida has taken one of the most prominent and aggressive stances against multiculturalism as often expressed from the nonwhite, non-straight viewpoint -- the "woke ideology," as DeSantis derisively calls it. Across the country, ABC News reported at least 10 states including Florida have passed legislation restricting diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives, with bills introduced in 19 other states. DeSantis had carried a running feud with the Walt Disney Company (the parent company of ESPN) for its opposition to DeSantis' Florida's Parental Rights in Education Act, known publicly as the "Don't Say Gay" bill. The American Civil Liberties Union accused Florida of being one of the states leading the country in classroom censorship after DeSantis signed the "Stop W.O.K.E. Act" -- which prohibits wide swaths of Black history to be taught -- into law. In response, grassroots movements in the state combined with the ACLU of Florida in November to announce Free to Be Florida, which describes itself as "a new coalition aimed at ensuring a safe and accurate learning environment free from government overreach and censorship." PEN America reported in September a 33% increase in public school book bans from two years ago, noting that, "Books about race and racism, LGBTQ+ identities have remained a top target."

"It's an embedded cultural acceptance of racism in this district and community," said Jacqueline Perez, a Fort Myers community organizer. "It is in every aspect of school, work, etc., of a child who is Black or brown in this community that a form of racism is affecting and impacting their lives and well-being." Within a nine-month span in 2015 and 2016, there were two separate incidents of racial images and epithets directed at the North Fort Myers High School baseball coach at the time, Tavaris Gary, who is Black. In 2015, video surfaced showing a previous baseball coach, David Bechtol, taking a sledgehammer to a wall in his home with a drawing of Gary with a noose around his neck. In 2016, the N-word and a swastika were found on a dugout wall at Joey Cross Field. These histories and sentiments permeated the baseball team. Another part of the Title VI investigation into the baseball team was hampered when a white interviewee felt "uncomfortable" being interviewed by two Black district administrators because both happened to be wearing T-shirts whose fronts read "Black History Month."

"This is Florida, and this is Robert-Period-E-Period-Lee County, and they live up to every drop of that name," Gwynetta Gittens said. In 2018, Gittens was elected to Lee County School Board -- she was the first Black person ever to be elected to the school board in the then-132-year history of Lee County. It was a historic achievement that spoke to the deeply entrenched hierarchy of the region. In 2022, she lost her seat. She sees the Fort Myers baseball team as a microcosm of the state and country, the result of the consequences of political rhetoric and polarization.

"As a Black person and as a leader this was very difficult because there's enough blame on both sides," she said. "Did you used to call each other n----s and b-----s? Yes, you did. Was it right for the coach to talk like that? No, it wasn't. Was it right to walk out on your own teammates? No, it wasn't. Unraveling this to me shows the need for more conversation, more understanding, not less. When I decided to run for school board, I would collect signatures. I would say, 'I'm just asking for your signature to be on the ballot.' People would ask me, 'Are you woke?' They would tell me the schools were teaching hate, and I would say, 'Please give me an example where you think education is teaching children to hate each other.' And now we're here. Kids just want to play flipping baseball."

Baseball would now be part of the culture war. Mark Lorenz, father of Kaden Lorenz and one of the leaders of the Green Wave Booster Club, adopted the language of the civil rights movement while supporting the walkout. Initially, he was disapproving of his son participating but changed his mind as it unfolded.

"Our sons did peaceful, nonviolent protest intended to get people's attention," he said. "They got to a point where enough was enough. I'm not a racist guy, and neither are any of the kids."

Michael Tucker was unmoved by the report's conclusion that race was not central to the protest. "If this was a protest for Kyle, then why didn't they protest the administration? Why didn't they protest the principal, the people making the decisions?" Tucker said. "Who did they take their protest out on? They took it out on the only two Black kids on the team. That's who they directed the protest at."

During her successful 2022 campaign for Lee County school board, Jada Langford-Fleming posted an Instagram video where she stated: "I'm proud to endorse Governor Ron DeSantis' education agenda and put students first. ... I'm running to rid our schools of anti-American critical race theory to ensure our campuses are safe and secure for our kids. I'm running to end woke ideologies and stop the indoctrination of our students." Langford-Fleming declined to comment to ESPN.

Earlier this month, DeSantis signed SB 1264, a bill requiring public schools to start teaching K-12 students in 2026 the "dangers and evils of Communism." "We will not allow our students to live in ignorance, nor be indoctrinated by Communist apologists in our schools," DeSantis said in an April 17 news release, which added that the bill is designed to "prepare students to withstand indoctrination on Communism at colleges and universities."

On his Facebook page, Burchfield, who also taught social studies and economics at Fort Myers, revels in the political divisions by lampooning President Joe Biden. The night of DeSantis' victory speech, Burchfield posted a meme calling DeSantis the "G-GOAT: Greatest Governor of All Time."

**AFTER BASEBALL CAME** a dizzying array of investigations. The school district already had begun a Title VI discrimination investigation following the Carcioppolo text, but sources in the Fort Myers educational community were dubious of Chuck Bradley, the man handling the discrimination case. Some sources were pessimistic about Bradley's ability to conduct a thorough, impartial investigation. One source said Bradley seemed more concerned with being friendly rather than known for his rigorous casework. Gwynetta Gittens did not have an opinion on Bradley's professionalism but was very watchful of a well-practiced Lee County tactic.

"They won't ever admit any wrongdoing, and instead will just quietly reassign people to different jobs within the district," Gittens said.

Led by Fernando Vazquez, the district's office of professional standards then opened an investigation into the walkout by investigating Hinson, the third-base coach. The Tuckers and Reillys retained legal counsel.

As the investigations painted a picture of mounting frustrations and personal grievances that ultimately led to the walkout, two themes emerged from the slew of interviews, text messages and personnel files: the degree to which athletic director Steven Cato knew in advance a protest was imminent but took no initiative to prevent it and how much Xavier Medina's fears were realized; and Cato not only knew and did not act, but the coaches and parents encouraged the walkout and pressured Cato to allow it.

One player told Vazquez that Hinson called him the night before the walkout, and Hinson explained how he planned on guaranteeing a canceled game: He would demote several players to the junior varsity. "He was saying if three seniors walked out, we wouldn't have enough to play," the student told investigators. "I was on the fence. ... I was trying to understand the logic and the reasoning for the walkout. Coach Hinson told us he wouldn't leave us to dry. If one of us walked out, so would he."

Hours before the game, the player's mother called Keeth Jones -- Jones had been brought in to assist during Burchfield's suspension and her son played basketball for him -- and told him of the call with Hinson. She added that she did not agree with the boycott, that her son did not want to jeopardize his chance to play college baseball.

According to his interview with Vazquez, Jones then told Cato of the walkout. "Cato did not say he would let admin know," he said. "I don't know what he did after I talked to him. I told Cato because of chain of command. He said if they decide to walk to let them go."

When Vazquez asked Cato if any administrators had spoken to the team and warned them of the consequence of a walkout, Cato responded, "No one presented that idea." He said one assistant principal, Kelly Heinzman-Britton, suggested the game be canceled, an idea he told investigators principal Butz rejected. "He said, it would be unfair to cancel a game as it would effect \[sic\] the kids who had nothing to do with it."

Hours before the boycott, Cato called Fort Myers Police Department officer Michael Perry, a former school resource officer at the high school, referring to the game as a "volatile situation." Yet Cato still maintained to investigators he had no previous knowledge the players would walk. When his story wavered, Cato would say there had been "rumors" of a walkout, but nothing definitive.

According to the details in Vazquez's Hinson report, Butz, Cato, Jones and Perry were all alerted in some way during the season of a possible protest action. None of them contacted parents, addressed the potentially striking players or took an action to cancel the game.

"It was like they let our kids walk into a trap," Shane Reilly said.

When it was over, the parent who had originally told Jones of its possibility, called Butz. "I talked to Dr. Butz the next day," she said. "I was embarrassed and sad due to the action of the coach, and admin knew and didn't stop it."

Piece by piece, the plan hatched. Before the first pitch, one Fort Myers player left the dugout demanding a reason from Jones why Burchfield was not coaching the game. Fort Myers assistant principal Toni Washington-Knight sat in the team dugout. As other players began packing their gear, she said to one, "We going to another dugout?" Washington-Knight told Vazquez the player "looked at me and smirked. They started to walk out."

Remaining on the field, Tucker and Reilly watched their teammates and classmates abandon them. Washington-Knight told investigators she urged Tucker and Reilly to remain on the field and "not get caught up in this." When Cato saw Hinson, the coach told him, "I'm going with my guys." Andrew Dailey, identified as a volunteer coach, told Cato: "You need to be a man and stand with us."

For nearly 20 minutes, the parents sparred. Perry ordered the boycotting parents to disperse. According to Fort Myers police bodycam footage, they did not. Dee Tucker and Melanie Reilly were convinced the players and parents did not want to leave. "They walked off the field, but wouldn't leave the park," Melanie Reilly said. "If they wanted to boycott, they should have gotten in their cars and gone home -- but they didn't." Under threat from Perry, the boycotters eventually dispersed. Andrew Dailey's wife was captured on Perry's bodycam footage telling him as she walked to her car: "I know it appears that they're the victims, but I'm going to tell you, we're the victims ... and these boys finally stood up for themselves."

**NEITHER SHANE NOR** Melanie Reilly had any confidence the long-delayed Title VI report would provide them comfort. When it was finally released July 17, their pessimism was confirmed. Chuck Bradley's heavily redacted 36-page report concluded that "Fort Myers High School administration and baseball program staff did not intentionally discriminate against individuals based on race, color, or national origin," and that "interventions and actions were attempted without regard to individuals' race, color, or national origin." If Bradley did not outrightly contradict his conclusion, he did find "evidence of policy and procedural violations, as well as misapplications including...ineffective and/or inadequate intervention. Throughout this series of incidents, there were multiple attempts to remedy situations and/or address parent and student concerns. However, many of these attempts were not effective in addressing concerns, especially regarding racist comments, the team divide, team relationships, parent relationships and misbehavior."

The Tuckers and Reillys were frustrated by Bradley's interpretation of the 1964 Civil Rights Act that for discrimination to occur, it needed to be intentional. Intentional or unintentional, both families felt their children were harmed by Carcioppolo's text and the racial climate at Fort Myers High.

Adding to the anger of the Reillys and the Tuckers was another of Bradley's conclusions: The bulk of discrimination may have been against white players, additional grist for the culture war. "While the reason for bias was alleged by some to be racially motivated," the report read, "the majority of complaints alleged that the bias was toward those of non-minority status and/or those who are perceived as non-minority."

"They keep telling us this isn't about race, and yet the whole thing began with a racist text message," Shane Reilly said. "How can that be?"

Several supporters of the coaches and school loudly claimed victory. On social media, a poster with the handle Scott Allan wrote: "Sorry but the Tucker's \[parents\] ought to be ashamed of himself. The whole thing was obvious from the get-go." Mark Lorenz, who first did not want his son involved in the walkout and then found himself immensely proud to be a part of it said: "They found the coaches did nothing wrong. It was a witch hunt." In the comments section on Burchfield's Facebook page, Lorenz posted a face-palm emoji, adding, "All that for nothing and EVERYONE already knew."

Burchfield himself joined in. On his Facebook page, Burchfield said he "could not have asked for more love and support" in "probably the most difficult time" in his life. He already had told investigators that the Reillys were upset about their son's playing time and "are using race as an excuse." After the report was released, he added a quote that would prove for him unfortunately prescient: "The time is coming when everything that is covered up will be revealed, and all that is secret will be made known to all. -- Luke 12:2."

On Sept. 1, however, the school district released an amendment to the Title VI investigation allegations that Hinson "may have walked out of a baseball game, while it was being played. It is alleged that the walkout was planned. It is also alleged that this act may involve equity/racism. The walking out may have exposed student(s) to unnecessary embarrassment or disparagement." The District "found just cause for disciplinary action" and Hinson was reprimanded due to "conduct unbecoming of a District employee." Hinson was transferred to Dunbar Middle School and banned from coaching for the 2023-24 school year.

Throughout the investigation, Burchfield told investigators how adversely he was being affected by the process, especially financially. He had told investigators he was concerned for his coaching prospects and told sources he was concerned about his scout position with the Braves. On his Facebook page, Burchfield prominently stated his affiliation with the club.

Burchfield, however, had been fabricating his involvement with the Braves. According to the team, Kyle Burchfield has never been associated with the club in any paid or official capacity.

"Mr. Burchfield was never an employee of the Atlanta Braves," the club told ESPN in a statement. "When we learned that he was representing himself as an employee of our club, we served Mr. Burchfield with a cease-and-desist letter demanding that he stop representing himself in this manner." In addition to the Braves' cease-and-desist to Burchfield, league sources said the Braves were required to refer Burchfield to MLB's security index.

In mid-October, following a public records request, the School District of Lee County released the Office of Professional Standards "investigation file" report by Vazquez on Hinson, detailing Hinson's role and Cato's inaction in a document that had less to do with Hinson specifically and more to do with the walkout. The Office of Professional Standards report provided the most damning portrait of adult behavior on the part of several parents and employees of Fort Myers High School.

The report was also nearly completed in early July, before the completion and release of the Title VI report but not released until mid-October. To the furious Reillys and Tuckers, it was another example of corruption within the school district. The combination of the three investigations revealed a far more damning picture of discrimination -- one to which the district would ultimately concur -- but Bradley's incomplete, largely exonerating report was the only one released to the public.

**WHILE INVESTIGATORS CONDUCTED** their interviews, Fort Myers High cleaned house. By summer, virtually every adult connected with the Fort Myers baseball team would no longer be associated with the school. The principal, Dr. Robert Butz, resigned just a few weeks after the walkout. Christian Engelhart was named principal.

Gwynetta Gittens' prediction that the district would reassign administrators was realized. Darya Grote, the assistant principal who was one of the administrators assigned to the team during the season but was not in the dugout on April 6, was promoted to principal of Lehigh Senior High School. Toni Washington-Knight, who was in the dugout the day of the walkout, was sent to Fort Myers Middle Academy, where she is currently assistant principal -- but not before providing a coda for her experience to investigators.

"Throughout the whole process I tried to stay unbiased," she testified. "I kept relationships with lots of the players up until that moment. I look at the kids differently ... those that walked out. I also look at the ones who stayed back differently."

Before the Title VI investigation was complete, Burchfield resigned and joined the staff at Naples High School in nearby Collier County and serves as the baseball team's pitching coach.

Cato nearly hired JV coach Chris Chappell as head baseball coach. Chappell was at first base during the walkout. The Vazquez report listed him among the coaches who "most likely" left the game that day. Chappell told investigators he left after Jones told him the game was forfeited. As the summer turned to fall, Cato informed parents he would be searching for a different head coach.

One member of the Lee County School Board aware of the full scope of the reports was Melisa Giovannelli, but she declined to discuss the matter because she is up for reelection and many of the families who supported the walkout were, in her words, "her voters."

"It's unfortunate but that's kind of where it's at, and this situation's been dealt with," she said in a voicemail to ESPN. "And unfortunately, I think to rehash it would do more harm than good, for me especially, and, um, somehow we have to move on from here."

Steven Cato, the athletic director who said he had heard rumors of a boycott and called police ahead of time but did nothing to alert the parents or stop the walkout once it began, remained in his same position. He is the only adult still associated with the baseball team who was affiliated with it at the time of the walkout.

"Under no circumstance do I believe Steven Cato protected my son," Shane Reilly said.

The baseball team has a new coach, Brad Crone, who once played at Estero High. In February, Madrid Tucker -- who had long been undecided about returning to baseball -- chose to return to the baseball team. The season cancellation dropped his rankings to 186th in the nation.

On Feb. 14, represented by prominent civil rights attorney Benjamin Crump, the Tuckers filed a federal discrimination lawsuit against the School Board of Lee County and the School District of Lee County, as well as seven individuals: Cato, Burchfield, Carcioppolo, Hinson, Chappell, former Fort Myers High principal Butz and Lee County School Superintendent Christopher Bernier, who resigned in mid-April.

Madrid Tucker enjoyed his junior year on the football team. He says his real friends are on the football team and associates with virtually none of his baseball teammates.

During a game March 12 against Cypress Lake, the opposing team yelled "Happy Valentine's Day" to Madrid Tucker.

"That just proves what the culture is here," Dee Tucker said.

Tate Reilly's high school baseball career ended. He says when he received his diploma, at least one former teammate booed as he walked across the graduation stage. Nearly completing his freshman year at Albertus Magnus, he says he is still "processing what happened."

"I am left wondering what they think I did to deserve all the hate," he said in an email to ESPN. "Coaches throw out things like 'tough love' or 'kids need discipline' ... The coaches made up lies to punish me. That is not discipline. That is abuse. ... Being a kid and having a fun year with family and friends was taken away from me. My future was not important to them ... and to this day, they don't care."

On April 8, like the Tuckers, the Reillys filed a federal lawsuit against Lee County Schools, the school board and seven defendants, alleging their actions "empowered students and adults to act in ways that caused further trauma and harm." The Reilly and Tucker lawsuits were assigned to Florida Middle District Judge Sheri Polster Chappell, a 2012 Obama District Court appointee. The wife of Chris Chappell, Polster Chappell recused herself from both cases.