"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Rebel Without a Cause (1955).md\"> Rebel Without a Cause (1955) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Clarence Thomas Secretly Accepted Luxury Trips From Major GOP Donor.md\"> Clarence Thomas Secretly Accepted Luxury Trips From Major GOP Donor </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Gambler Who Beat Roulette Found Way to Win Beyond Red or Black.md\"> Gambler Who Beat Roulette Found Way to Win Beyond Red or Black </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Saving the Horses of Our Imagination.md\"> Saving the Horses of Our Imagination </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Brilliant Inventor Who Made Two of History’s Biggest Mistakes.md\"> The Brilliant Inventor Who Made Two of History’s Biggest Mistakes </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/How an FBI agent stained an NCAA basketball corruption probe - Los Angeles Times.md\"> How an FBI agent stained an NCAA basketball corruption probe - Los Angeles Times </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Leopards Are Living among People. And That Could Save the Species.md\"> Leopards Are Living among People. And That Could Save the Species </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Why Joe Biden’s Honeymoon With Progressives Is Coming to an End.md\"> Why Joe Biden’s Honeymoon With Progressives Is Coming to an End </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Striking French workers dispute that they want a right to ‘laziness’.md\"> Striking French workers dispute that they want a right to ‘laziness’ </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Les Combrailles, à la découverte de l’Auvergne secrète.md\"> Les Combrailles, à la découverte de l’Auvergne secrète </a>"

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Why Joe Biden’s Honeymoon With Progressives Is Coming to an End.md\"> Why Joe Biden’s Honeymoon With Progressives Is Coming to an End </a>"

],

"Renamed":[

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.04 Cinematheque/Rebel Without a Cause (1955).md\"> Rebel Without a Cause (1955) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Clarence Thomas Secretly Accepted Luxury Trips From Major GOP Donor.md\"> Clarence Thomas Secretly Accepted Luxury Trips From Major GOP Donor </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Gambler Who Beat Roulette Found Way to Win Beyond Red or Black.md\"> Gambler Who Beat Roulette Found Way to Win Beyond Red or Black </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Saving the Horses of Our Imagination.md\"> Saving the Horses of Our Imagination </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"02.03 Zürich/Miss Miu.md\"> Miss Miu </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.01 Admin/Calendars/Events/2023-04-08 FC Zürich - FC Basel (1-1).md\"> 2023-04-08 FC Zürich - FC Basel (1-1) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.04 Cinematheque/The Guard (2011).md\"> The Guard (2011) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Big Coin Heist.md\"> The Big Coin Heist </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Big Coin Heist.md\"> The Big Coin Heist </a>",

@ -9367,18 +9416,18 @@

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Striking French workers dispute that they want a right to ‘laziness’.md\"> Striking French workers dispute that they want a right to ‘laziness’ </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Law Roach on Why He Retired From Celebrity Fashion Styling.md\"> Law Roach on Why He Retired From Celebrity Fashion Styling </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Is Fox News Really Doomed.md\"> Is Fox News Really Doomed </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Le Camp des Saints.md\"> Le Camp des Saints </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Camp of the Saints.md\"> The Camp of the Saints </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.01 Reading list/The Power And The Glory.md\"> The Power And The Glory </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Bull elephants – their importance as individuals in elephant societies - Africa Geographic.md\"> Bull elephants – their importance as individuals in elephant societies - Africa Geographic </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Silicon Valley Bank Contagion Is Just Beginning.md\"> The Silicon Valley Bank Contagion Is Just Beginning </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.04 Cinematheque/John Wick (2014).md\"> John Wick (2014) </a>"

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Le Camp des Saints.md\"> Le Camp des Saints </a>"

],

"Tagged":[

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"04.01 lebv.org/Les Le Bastart de Villeneuve.md\"> Les Le Bastart de Villeneuve </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Clarence Thomas Secretly Accepted Luxury Trips From Major GOP Donor.md\"> Clarence Thomas Secretly Accepted Luxury Trips From Major GOP Donor </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Saving the Horses of Our Imagination.md\"> Saving the Horses of Our Imagination </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Gambler Who Beat Roulette Found Way to Win Beyond Red or Black.md\"> Gambler Who Beat Roulette Found Way to Win Beyond Red or Black </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"02.03 Zürich/Miss Miu.md\"> Miss Miu </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Big Coin Heist.md\"> The Big Coin Heist </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Unimaginable Horror of Evan Gershkovich’s Arrest in Moscow.md\"> The Unimaginable Horror of Evan Gershkovich’s Arrest in Moscow </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/We want objective judges and doctors. Why not journalists too.md\"> We want objective judges and doctors. Why not journalists too </a>",

@ -9420,16 +9469,7 @@

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Mel Brooks Isn’t Done Punching Up the History of the World.md\"> Mel Brooks Isn’t Done Punching Up the History of the World </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The One Big Question Bernie Sanders Won’t Answer.md\"> The One Big Question Bernie Sanders Won’t Answer </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/On the Trail of the Fentanyl King.md\"> On the Trail of the Fentanyl King </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Humans Started Riding Horses 5,000 Years Ago, New Evidence Suggests.md\"> Humans Started Riding Horses 5,000 Years Ago, New Evidence Suggests </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/On the Trail of the Fentanyl King.md\"> On the Trail of the Fentanyl King </a>"

],

"Refactored":[

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"05.01 Computer setup/Storage and Syncing.md\"> Storage and Syncing </a>",

@ -9485,6 +9525,9 @@

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.01 Admin/Calendars/2022-10-03 Meggi leaving to Belfast.md\"> 2022-10-03 Meggi leaving to Belfast </a>"

],

"Deleted":[

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"02.02 Paris/Andy Wahlou.md\"> Andy Wahlou </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.01 Admin/Calendars/Events/2023-04-07 Mum in Zürich.md\"> 2023-04-07 Mum in Zürich </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Test.md\"> Test </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Why are Americans dying so young.md\"> Why are Americans dying so young </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/How Michael Cohen’s Big Mouth Could Be Derailing the Trump Prosecution.md\"> How Michael Cohen’s Big Mouth Could Be Derailing the Trump Prosecution </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Les Combrailles, à la découverte de l’Auvergne secrète.md\"> Les Combrailles, à la découverte de l’Auvergne secrète </a>",

@ -9532,12 +9575,29 @@

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.01 Admin/Calendars/2022-12-15 Test.md\"> 2022-12-15 Test </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Life admin.md\"> Life admin </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"Media DB/movies/Tomorrow Never Dies (1997).md\"> Tomorrow Never Dies (1997) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/‘The Hole’ Gruesome Accounts of Russian Occupation Emerge From Ukrainian Nuclear Plant.md\"> ‘The Hole’ Gruesome Accounts of Russian Occupation Emerge From Ukrainian Nuclear Plant </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Gisele Bündchen on Tom Brady, FTX Blind Side, and Being a “Witch of Love”.md\"> Gisele Bündchen on Tom Brady, FTX Blind Side, and Being a “Witch of Love” </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Clarence Thomas Secretly Accepted Luxury Trips From Major GOP Donor.md\"> Clarence Thomas Secretly Accepted Luxury Trips From Major GOP Donor </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Saving the Horses of Our Imagination.md\"> Saving the Horses of Our Imagination </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Gambler Who Beat Roulette Found Way to Win Beyond Red or Black.md\"> Gambler Who Beat Roulette Found Way to Win Beyond Red or Black </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/We want objective judges and doctors. Why not journalists too.md\"> We want objective judges and doctors. Why not journalists too </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/I Went on a Package Trip for Millennials Who Travel Alone. Help Me..md\"> I Went on a Package Trip for Millennials Who Travel Alone. Help Me. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.04 Cinematheque/The Guard (2011).md\"> The Guard (2011) </a>",

@ -9568,27 +9628,7 @@

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Adam Sandler doesn’t need your respect. But he’s getting it anyway..md\"> Adam Sandler doesn’t need your respect. But he’s getting it anyway. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Gisele Bündchen on Tom Brady, FTX Blind Side, and Being a “Witch of Love”.md\"> Gisele Bündchen on Tom Brady, FTX Blind Side, and Being a “Witch of Love” </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Jaylen Brown Is Trying to Find a Balance.md\"> Jaylen Brown Is Trying to Find a Balance </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/I Went on a Package Trip for Millennials Who Travel Alone. Help Me..md\"> I Went on a Package Trip for Millennials Who Travel Alone. Help Me. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Limits and Wonders of John Wick’s Last Fight.md\"> The Limits and Wonders of John Wick’s Last Fight </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Mel Brooks Isn’t Done Punching Up the History of the World.md\"> Mel Brooks Isn’t Done Punching Up the History of the World </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/An Icelandic Town Goes All Out to Save Baby Puffins.md\"> An Icelandic Town Goes All Out to Save Baby Puffins </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How an FBI agent stained an NCAA basketball corruption probe.md\"> How an FBI agent stained an NCAA basketball corruption probe </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Last Stand of the Hot Dog King.md\"> Last Stand of the Hot Dog King </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Limits and Wonders of John Wick’s Last Fight.md\"> The Limits and Wonders of John Wick’s Last Fight </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Last Stand of the Hot Dog King.md\"> Last Stand of the Hot Dog King </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Silicon Valley Bank Contagion Is Just Beginning.md\"> The Silicon Valley Bank Contagion Is Just Beginning </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Jaylen Brown Is Trying to Find a Balance.md\"> Jaylen Brown Is Trying to Find a Balance </a>"

],

"Removed Tags from":[

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/‘Incredibly intelligent, highly elusive’ US faces new threat from Canadian ‘super pig’.md\"> ‘Incredibly intelligent, highly elusive’ US faces new threat from Canadian ‘super pig’ </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/‘Incredibly intelligent, highly elusive’ US faces new threat from Canadian ‘super pig’.md\"> ‘Incredibly intelligent, highly elusive’ US faces new threat from Canadian ‘super pig’ </a>",

- [ ] 10:35 :chair: [[2023-01-03|Memo]], [[@Life Admin|Admin]], [[@@MRCK|Meggi]]: Find a person to repair Meggi's chair 📅 2023-05-31 ^fqrywu

@ -95,7 +95,7 @@ This section does serve for quick memos.

- [x] 11:53 :wine_glass: [[2023-01-03|Memo]], [[@Lifestyle|Lifestyle]], [[!!Wine|Wine]]: Order a couple of boxes of [[Nadine Saxer - Blanc de Noir]] 📅 2023-01-31 ✅ 2023-01-04

- [x] 11:57 🐛 [[2023-01-03|Memo]], [[@Life Admin|Admin]]: Eradicate flies & such in the kitchen 📅 2023-01-15 ✅ 2023-01-04

- [x] 12:24 :hospital: [[2023-01-03|Memo]], [[@Lifestyle|Lifestyle]]: Find a charity shop in [[@@Zürich|ZH]] to give away clothes 📅 2023-01-10 ✅ 2023-01-04

# Clarence Thomas Secretly Accepted Luxury Trips From Major GOP Donor

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive [our biggest stories](https://www.propublica.org/newsletters/the-big-story?source=www.propublica.org&placement=top-note®ion=national) as soon as they’re published.

**Update, April 7, 2023:** Since publication, [Justice Clarence Thomas has made a public statement](https://www.propublica.org/article/clarence-thomas-response-trips-legal-experts-harlan-crow) defending his undisclosed trips.

In late June 2019, right after the U.S. Supreme Court released its final opinion of the term, Justice Clarence Thomas boarded a large private jet headed to Indonesia. He and his wife were going on vacation: nine days of island-hopping in a volcanic archipelago on a superyacht staffed by a coterie of attendants and a private chef.

If Thomas had chartered the plane and the 162-foot yacht himself, the total cost of the trip could have exceeded $500,000. Fortunately for him, that wasn’t necessary: He was on vacation with real estate magnate and Republican megadonor Harlan Crow, who owned the jet — and the yacht, too.

Clarence Thomas and his wife, Ginni, front left, with Harlan Crow, back right, and others in Flores, Indonesia, in July 2019. Credit: via Instagram

For more than two decades, Thomas has accepted luxury trips virtually every year from the Dallas businessman without disclosing them, documents and interviews show. A public servant who has a salary of $285,000, he has vacationed on Crow’s superyacht around the globe. He flies on Crow’s [Bombardier Global 5000](https://defense.bombardier.com/en/aircraft/global-5000) jet. He has gone with Crow to the Bohemian Grove, the exclusive California all-male retreat, and to Crow’s sprawling ranch in East Texas. And Thomas typically spends about a week every summer at Crow’s private resort in the Adirondacks.

The extent and frequency of Crow’s apparent gifts to Thomas have no known precedent in the modern history of the U.S. Supreme Court.

These trips appeared nowhere on Thomas’ financial disclosures. His failure to report the flights appears to violate a law passed after Watergate that requires justices, judges, members of Congress and federal officials to disclose most gifts, two ethics law experts said. He also should have disclosed his trips on the yacht, these experts said.

Thomas did not respond to a detailed list of questions.

In a [statement](https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/23741877-harlan-crow-statement), Crow acknowledged that he’d extended “hospitality” to the Thomases “over the years,” but said that Thomas never asked for any of it and it was “no different from the hospitality we have extended to our many other dear friends.”

Through his largesse, Crow has gained a unique form of access, spending days in private with one of the most powerful people in the country. By accepting the trips, Thomas has broken long-standing norms for judges’ conduct, ethics experts and four current or retired federal judges said.

“It’s incomprehensible to me that someone would do this,” said Nancy Gertner, a retired federal judge appointed by President Bill Clinton. When she was on the bench, Gertner said, she was so cautious about appearances that she wouldn’t mention her title when making dinner reservations: “It was a question of not wanting to use the office for anything other than what it was intended.”

Virginia Canter, a former government ethics lawyer who served in administrations of both parties, said Thomas “seems to have completely disregarded his higher ethical obligations.”

“When a justice’s lifestyle is being subsidized by the rich and famous, it absolutely corrodes public trust,” said Canter, now at the watchdog group CREW. “Quite frankly, it makes my heart sink.”

> When a justice’s lifestyle is being subsidized by the rich and famous, it absolutely corrodes public trust. Quite frankly, it makes my heart sink.

—Virginia Canter, former government ethics lawyer

ProPublica uncovered the details of Thomas’ travel by drawing from flight records, internal documents distributed to Crow’s employees and interviews with dozens of people ranging from his superyacht’s staff to members of the secretive Bohemian Club to an Indonesian scuba diving instructor.

Federal judges sit in a unique position of public trust. They have lifetime tenure, a privilege intended to insulate them from the pressures and potential corruption of politics. A code of conduct for federal judges below the Supreme Court requires them to avoid even the “appearance of impropriety.” Members of the high court, Chief Justice John Roberts has written, “consult” that code for guidance. The Supreme Court is left almost entirely to police itself.

There are few restrictions on what gifts justices can accept. That’s in contrast to the other branches of government. Members of Congress are generally prohibited from taking gifts worth $50 or more and would need pre-approval from an ethics committee to take many of the trips Thomas has accepted from Crow.

Thomas’ approach to ethics has already attracted public attention. Last year, Thomas didn’t recuse himself from cases that touched on the involvement of his wife, Ginni, in efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election. While his decision generated outcry, it could not be appealed.

Crow met Thomas after he became a justice. The pair have become genuine friends, according to people who know both men. Over the years, some details of Crow’s relationship with the Thomases have emerged. In 2011, The New York Times [reported](https://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/19/us/politics/19thomas.html) on Crow’s generosity toward the justice. That same year, Politico [revealed](https://www.politico.com/story/2011/02/justice-thomass-wife-now-lobbyist-048812) that Crow had given half a million dollars to a Tea Party group founded by Ginni Thomas, which also paid her a $120,000 salary. But the full scale of Crow’s benefactions has never been revealed.

Long an influential figure in pro-business conservative politics, Crow has spent millions on ideological efforts to shape the law and the judiciary. Crow and his firm have not had a case before the Supreme Court since Thomas joined it, though the court periodically hears major cases that directly impact the real estate industry. The details of his discussions with Thomas over the years remain unknown, and it is unclear if Crow has had any influence on the justice’s views.

In his [statement](https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/23741877-harlan-crow-statement), Crow said that he and his wife have never discussed a pending or lower court case with Thomas. “We have never sought to influence Justice Thomas on any legal or political issue,” he added.

In Thomas’ public appearances over the years, he has presented himself as an everyman with modest tastes.

“I don’t have any problem with going to Europe, but I prefer the United States, and I prefer seeing the regular parts of the United States,” Thomas said in a recent interview for a documentary about his life, which Crow helped finance.

“I prefer the RV parks. I prefer the Walmart parking lots to the beaches and things like that. There’s something normal to me about it,” Thomas said. “I come from regular stock, and I prefer that — I prefer being around that.”

### “You Don’t Need to Worry About This — It’s All Covered”

Crow’s private lakeside resort, Camp Topridge, sits in a remote corner of the Adirondacks in upstate New York. Closed off from the public by ornate wooden gates, the 105-acre property, once the summer retreat of the same heiress who built Mar-a-Lago, features an artificial waterfall and a great hall where Crow’s guests are served meals prepared by private chefs. Inside, there’s clear evidence of Crow and Thomas’ relationship: a painting of the two men at the resort, sitting outdoors smoking cigars alongside conservative political operatives. A statue of a Native American man, arms outstretched, stands at the center of the image, which is photographic in its clarity.

A painting that hangs at Camp Topridge shows Crow, far right, and Thomas, second from right, smoking cigars at the resort. They are joined by lawyers Peter Rutledge, Leonard Leo and Mark Paoletta, from left. Credit: Painting by Sharif Tarabay

The painting captures a scene from around five years ago, said Sharif Tarabay, the artist who was commissioned by Crow to paint it. Thomas has been vacationing at Topridge virtually every summer for more than two decades, according to interviews with more than a dozen visitors and former resort staff, as well as records obtained by ProPublica. He has fished with a guide hired by Crow and danced at concerts put on by musicians Crow brought in. Thomas has slept at perhaps the resort’s most elegant accommodation, an opulent lodge overhanging Upper St. Regis Lake.

The mountainous area draws billionaires from across the globe. Rooms at a nearby hotel built by the Rockefellers start at $2,250 a night. Crow’s invitation-only resort is even more exclusive. Guests stay for free, enjoying Topridge’s more than 25 fireplaces, three boathouses, clay tennis court and batting cage, along with more eccentric features: a lifesize replica of the Harry Potter character Hagrid’s hut, bronze statues of gnomes and a 1950s-style soda fountain where Crow’s staff fixes milkshakes.

First image: A lodge at Topridge where Thomas has stayed. Second image: Thomas fishing in the Adirondacks. Credit: First image: Courtesy of Carolyn Belknap. Second image: Via NYup.com.

Crow’s access to the justice extends to anyone the businessman chooses to invite along. Thomas’ frequent vacations at Topridge have brought him into contact with corporate executives and political activists.

During just one trip in July 2017, Thomas’ fellow guests included executives at Verizon and PricewaterhouseCoopers, major Republican donors and one of the leaders of the American Enterprise Institute, a pro-business conservative think tank, according to records reviewed by ProPublica. The painting of Thomas at Topridge shows him in conversation with [Leonard Leo](https://www.propublica.org/article/dark-money-leonard-leo-barre-seid), the Federalist Society leader regarded as an [architect of the Supreme Court’s recent turn](https://www.propublica.org/article/dark-money-leonard-leo-barre-seid) to the right.

In his statement to ProPublica, Crow said he is “unaware of any of our friends ever lobbying or seeking to influence Justice Thomas on any case, and I would never invite anyone who I believe had any intention of doing that.”

“These are gatherings of friends,” Crow said.

Crow has deep connections in conservative politics. The heir to a real estate fortune, Crow oversees his family’s business empire and recently [named](https://www.hbscdallas.org/s/1738/cc/21/page.aspx?sid=1738&gid=23&pgid=71466) Marxism as his greatest fear. He was an early patron of the powerful anti-tax group Club for Growth and has been on the board of AEI for over 25 years. He also sits on the board of the Hoover Institution, another conservative think tank.

A major Republican donor for decades, Crow has given more than $10 million in publicly disclosed political contributions. He’s also given to groups that keep their donors secret — how much of this so-called dark money he’s given and to whom are not fully known. “I don’t disclose what I’m not required to disclose,” Crow once [told](https://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/05/us/politics/05thomas.html) the Times.

Crow has long supported efforts to move the judiciary to the right. He has donated to the Federalist Society and given millions of dollars to groups dedicated to tort reform and conservative jurisprudence. AEI and the Hoover Institution publish scholarship advancing conservative legal theories, and fellows at the think tanks occasionally file [amicus briefs](https://www.hoover.org/news/hoover-senior-fellows-file-supreme-court-amicus-brief-case-challenging-president-bidens) with the Supreme Court.

> I prefer the RV parks. I prefer the Walmart parking lots to the beaches and things like that. There’s something normal to me about it. I come from regular stock, and I prefer that — I prefer being around that.

—Clarence Thomas

Listen to Thomas speak, from the documentary “Created Equal.”

On the court since 1991, Thomas is a deeply conservative jurist known for his “originalism,” an approach that seeks to adhere to close readings of the text of the Constitution. While he has been resolute in this general approach, his views on specific matters have sometimes evolved. Recently, Thomas [harshly criticized](https://news.yahoo.com/thomas-criticizes-previous-high-court-173603914.html) one of his own earlier opinions as he embraced a legal theory, newly popular on the right, that would limit government regulation. Small evolutions in a justice’s thinking or even select words used in an opinion can affect entire bodies of law, and shifts in Thomas’ views can be especially consequential. He’s taken unorthodox legal positions that have been adopted by the court’s majority years down the line.

Soon after Crow met Thomas three decades ago, he began lavishing the justice with gifts, including a $19,000 Bible that belonged to Frederick Douglass, which Thomas disclosed. Recently, Crow gave Thomas a portrait of the justice and his wife, according to Tarabay, who painted it. Crow’s foundation also gave $105,000 to Yale Law School, Thomas’ alma mater, for the “Justice Thomas Portrait Fund,” tax filings show.

Crow said that he and his wife have funded a number of projects that celebrate Thomas. “We believe it is important to make sure as many people as possible learn about him, remember him and understand the ideals for which he stands,” he said.

To trace Thomas’ trips around the world on Crow’s superyacht, ProPublica spoke to more than 15 former yacht workers and tour guides and obtained records documenting the ship’s travels.

On the Indonesia trip in the summer of 2019, Thomas flew to the country on Crow’s jet, according to another passenger on the plane. Clarence and Ginni Thomas were traveling with Crow and his wife, Kathy. Crow’s yacht, the Michaela Rose, decked out with motorboats and a giant inflatable rubber duck, met the travelers at a fishing town on the island of Flores.

First image: From left, Crow, Paoletta, Ginni Thomas and Clarence Thomas in Indonesia in 2019. Clarence Thomas flew to the country on Crow’s jet, according to another passenger on the plane. Second image: A worker from Crow’s yacht ferries Thomas and others on a small boat in Indonesia. Credit: via Facebook

Touring the Lesser Sunda Islands, the group made stops at Komodo National Park, home of the eponymous reptiles; at the volcanic lakes of Mount Kelimutu; and at Pantai Meko, a spit of pristine beach accessible only by boat. Another guest was Mark Paoletta, a friend of the Thomases then serving as the general counsel of the Office of Management and Budget in the administration of President Donald Trump.

Paoletta was bound by executive branch ethics rules at the time and told ProPublica that he discussed the trip with an ethics lawyer at his agency before accepting the Crows’ invitation. “Based on that counsel’s advice, I reimbursed Harlan for the costs,” Paoletta said in an email. He did not respond to a question about how much he paid Crow.

(Paoletta has long been a pugnacious defender of Thomas and [recently testified](https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/23742060-paoletta-testimony-20220427) before Congress against strengthening judicial ethics rules. “There is nothing wrong with ethics or recusals at the Supreme Court,” he said, adding, “To support any reform legislation right now would be to validate these vicious political attacks on the Supreme Court,” referring to criticism of Thomas and his wife.)

The Indonesia vacation wasn’t Thomas’ first time on the Michaela Rose. He went on a river day trip around Savannah, Georgia, and an extended cruise in New Zealand roughly a decade ago.

During a New Zealand trip on Crow’s yacht, Thomas signed a copy of his memoir and gave it to a yacht worker. Credit: Obtained by ProPublica

As a token of his appreciation, he gave one yacht worker a copy of his memoir. Thomas signed the book: “Thank you so much for all your hard work on our New Zealand adventure.”

Crow’s policy was that guests didn’t pay, former Michaela Rose staff said. “You don’t need to worry about this — it’s all covered,” one recalled the guests being told.

There’s evidence Thomas has taken even more trips on the superyacht. Crow often gave his guests custom polo shirts commemorating their vacations, according to staff. ProPublica found photographs of Thomas wearing at least two of those shirts. In one, he wears a blue polo shirt embroidered with the Michaela Rose’s logo and the words “March 2007” and “Greek Islands.”

Thomas didn’t report any of the trips ProPublica identified on his annual [financial disclosures](https://www.courtlistener.com/person/3200/disclosure/30783/clarence-thomas/). Ethics experts said [the law](https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/23740274-financial_disclosure_filing_instructions#document/p28) clearly requires disclosure for private jet flights and Thomas appears to have violated it.

Thomas has been photographed wearing custom polo shirts bearing the logo of Crow’s yacht, the Michaela Rose. Credit: via Flickr, Washington Examiner

Justices are generally required to publicly report all gifts worth more than $415, defined as “anything of value” that isn’t fully reimbursed. There are exceptions: If someone hosts a justice at their own property, free food and lodging don’t have to be disclosed. That would exempt dinner at a friend’s house. The exemption never applied to transportation, such as private jet flights, experts said, a fact that was made explicit in recently updated [filing instructions](https://www.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/financial_disclosure_filing_instructions.pdf) for the judiciary.

Two ethics law experts told ProPublica that Thomas’ yacht cruises, a form of transportation, also required disclosure.

“If Justice Thomas received free travel on private planes and yachts, failure to report the gifts is a violation of the disclosure law,” said Kedric Payne, senior director for ethics at the nonprofit government watchdog Campaign Legal Center. (Thomas himself once reported receiving a private jet trip from Crow, on his disclosure for 1997.)

The experts said Thomas’ stays at Topridge may have required disclosure too, in part because Crow owns it not personally but through a company. Until recently, the judiciary’s ethics guidance didn’t explicitly address the ownership issue. The recent update to the filing instructions clarifies that disclosure is required for such stays.

How many times Thomas failed to disclose trips remains unclear. Flight records from the Federal Aviation Administration and FlightAware suggest he makes regular use of Crow’s plane. The jet often follows a pattern: from its home base in Dallas to Washington Dulles airport for a brief stop, then on to a destination Thomas is visiting and back again.

ProPublica identified five such trips in addition to the Indonesia vacation.

On July 7 last year, Crow’s jet made a 40-minute stop at Dulles and then flew to a small airport near Topridge, returning to Dulles six days later. Thomas was at the resort that week for his regular summer visit, according to a person who was there. Twice in recent years, the jet has followed the pattern when Thomas appeared at Crow’s properties in Dallas — once for the Jan. 4, 2018, [swearing-in](https://twitter.com/SenTedCruz/status/949083663915995136/photo/1) of Fifth Circuit Judge James Ho at Crow’s private library and again for a conservative think tank conference Crow hosted last May.

Thomas has even used the plane for a three-hour trip. On Feb. 11, 2016, the plane flew from Dallas to Dulles to New Haven, Connecticut, before flying back later that afternoon. ProPublica confirmed that Thomas was on the jet through Supreme Court security records [obtained by](https://fixthecourt.com/usms-all/) the nonprofit Fix the Court, private jet data, a [New Haven plane spotter](https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=968235546589129) and another person at the airport. There are no reports of Thomas making a public appearance that day, and the purpose of the trip remains unclear.

Jet charter companies told ProPublica that renting an equivalent plane for the New Haven trip could cost around $70,000.

On the weekend of Oct. 16, 2021, Crow’s jet repeated the pattern. That weekend, Thomas and Crow traveled to a Catholic cemetery in a bucolic suburb of New York City. They were there for the unveiling of a bronze statue of the justice’s beloved eighth grade teacher, a nun, according to Catholic Cemetery magazine.

Thomas attended the 2021 unveiling of a statue of his eighth grade teacher. Credit: via Catholic Cemeteries of the Archdiocese of Newark

As Thomas spoke from a lectern, the monument towered over him, standing 7 feet tall and weighing 1,800 pounds, its granite base inscribed with words his teacher once told him. Thomas told the nuns assembled before him, “This extraordinary statue is dedicated to you sisters.”

He also thanked the donors who paid for the statue: Harlan and Kathy Crow.

Do you have any tips on the courts? Josh Kaplan can be reached by email at [joshua.kapl\[emailprotected\]](https://www.propublica.org/cdn-cgi/l/email-protection#4923263a213c286722283925282709393b26393c2b25202a2867263b2e) and by Signal or WhatsApp at 734-834-9383. Justin Elliott can be reached by email at [\[emailprotected\]](https://www.propublica.org/cdn-cgi/l/email-protection#f9938c8a8d9097b9898b96898c9b95909a98d7968b9e) or by Signal or WhatsApp at 774-826-6240.

Matt Easton contributed reporting.

Design and development by [Anna Donlan](https://www.propublica.org/people/anna-donlan) and [Lena V. Groeger](https://www.propublica.org/people/lena-groeger).

# Gambler Who Beat Roulette Found Way to Win Beyond Red or Black

Photo Illustration by Irene Suosalo; Video: Getty Images

For decades, casinos scoffed as mathematicians and physicists devised elaborate systems to take down the house. Then an unassuming Croatian’s winning strategy forever changed the game.

April 6, 2023, 12:01 AM UTC

One spring evening, two men and a woman walked into the Ritz Club casino, an upmarket establishment in London’s West End. Security officers in a back room logged their entry and watched a grainy CCTV feed as the trio strolled past high gilded arches and oil paintings of gentlemen posing in hats. Casino workers greeted them with hushed reverence.

The security team paid particularly close attention to one of the three, their apparent leader. Niko Tosa, a Croatian with rimless glasses balanced on the narrow ridge of his nose, scanned the gaming floor, attentive as a hawk. He’d visited the Ritz half a dozen times over the previous two weeks, astounding staff with his knack for roulette and walking away with several thousand pounds each time. A manager would later say in a written statement that Tosa was the most successful player he’d witnessed in 25 years on the job. No one had any idea how Tosa did it. The casino inspected a wheel he’d played at for signs of tampering and found none.

That night, March 15, 2004, the thin Croatian seemed to be looking for something. After a few minutes, he settled at a roulette table in the Carmen Room, set apart from the main playing area. He was flanked on either side by his companions: a Serbian businessman with deep bags under his eyes and a bottle-blond Hungarian woman. At the end of the table, the wheel spun silently, spotlighted by a golden chandelier. The trio bought chips and began to play.

The Ritz Club casino in London in 2005. James Veysey/Camera Press/Redux

The Ritz was typical of London’s top casinos in that it was members-only and attracted an eclectic mix of old money, new money and dubiously acquired money. Britain’s royals were regulars, as were Saudi heiresses, hedge fund tycoons and the actor Johnny Depp. One cigar-chomping Greek diplomat was so dedicated to gambling he refused to leave his seat to use the toilet, instead urinating into a jug, so the story went.

But the way Tosa and his friends played roulette stood out as weird even for the Ritz. They would wait until six or seven seconds after the croupier launched the ball, when the rattling tempo of plastic on wood started to slow, then jump forward to place their chips before bets were halted, covering as many as 15 numbers at once. They moved so quickly and harmoniously, it was “as if someone had fired a starting gun,” an assistant manager told investigators afterward. The wheel was a standard European model: 37 red and black numbered pockets in a seemingly random sequence—32, 15, 19, 4 and so on—with a single green 0. Tosa’s crew was drawn to an area of the betting felt set aside for special wagers that covered pie-sliced segments of the wheel. There, gamblers could choose sections called *orphelins* (orphans) or *le tiers du cylindre* (a third of the wheel). Tosa and his partners favored “neighbors” bets, consisting of one number plus the two on each side, five pockets in all.

Then there was the win rate. Tosa’s crew didn’t hit the right number on every spin, but they did as often as not, in streaks that defied logic: eight in a row, or 10, or 13. Even with a dozen chips on the table at a total cost of £1,200 (about $2,200 at the time), the 35:1 payout meant they could more than double their money. Security staff watched nervously as their chip stack grew ever higher. Tosa and the Serbian, who did most of the gambling while their female companion ordered drinks, had started out with £30,000 and £60,000 worth of chips, respectively, and in no time both had broken six figures. Then they started to increase their bets, risking as much as £15,000 on a single spin.

It was almost as if they could see the future. They didn’t react whether they won or lost; they simply played on. At one point, the Serbian threw down £10,000 in chips and looked away idly as the ball bounced around the numbered pockets. He wasn’t even watching when it landed and he lost. He was already walking off in the direction of the bar.

It wasn’t the amount of money at stake that made the Ritz security team anxious. Customers routinely made several million pounds in an evening and left carrying designer bags bulging with cash. It was the way these three were winning: consistently, over hundreds of rounds. “It is practically impossible to predict the number that will come up,” Stephen Hawking once wrote about roulette. “Otherwise physicists would make a fortune at casinos.” The game was designed to be random; chaos, elegantly rendered in circular motion.

Even so, gamblers have come up with plenty of elaborate mathematical systems to beat it—Oscar’s Grind, the D’Alembert. Simple ones, too, such as betting on black then doubling on every loss until you win. Casino owners love these strategies because they don’t work. The green 0 pocket (with an additional 00 pocket on American wheels) means even the highest-odds bets, on red or black for example, have a slightly less than half chance of success. Everyone loses eventually.

Except for Niko Tosa and his friends. When the Croatian left the casino in the early hours of March 16, he’d turned £30,000 worth of chips into a £310,000 check. His Serbian partner did even better, making £684,000 from his initial £60,000. He asked for a half-million in two checks and the rest in cash. That brought the group’s take, including from earlier sessions, to about £1.3 million. And Tosa wasn’t done. He told casino employees he planned to return the next day.

A week later—after the events at the Ritz had been picked over by casino staff, roulette wheel engineers, police and lawyers—the British press got wind of Tosa’s epic run. The Mirror reported that an unidentified high-tech gang had hit the casino with a “laser scam,” pairing a device hidden in a mobile phone with a microcomputer to achieve the impossible.

It was as good a theory as any. But closer observers weren’t so sure, and the case remained a mystery even to casino insiders almost two decades later. “We still lose sleep over that one,” a gambling executive told me.

I spent six months investigating the clandestine world of professional roulette players to find out who Tosa is and how he beat the system. The search took me deep into a secret war between those who make a living betting on the wheel and those who try to stop them—and ultimately to an encounter with Tosa himself. The British press got plenty wrong in their reports about what happened on the night of March 15, 2004. There was no laser. But the newspapers were right about one thing: It is possible to beat roulette.

John Wootten had just finished his first day as security chief at the Ritz when he got a call from a colleague about some unusual activity at the roulette tables. He was in a West End pub having a beer with friends, celebrating his new job at one of the city’s most prestigious venues.

We’re losing money rapidly, the voice on the other end of the phone told him. What should we do? Get the names of the gamblers and call back, Wootten said.

Wootten was a burly former soldier in the Grenadier Guards, whose red coats and bearskin hats can be seen guarding Buckingham Palace. He also ran a punk rock pub before getting into the casino business. Wootten knew to brace himself for trouble. Casino staff didn’t call so late without good reason.

Word came back by the time he’d finished his pint. One of the players was Niko Tosa. The others were Nenad Marjanovic—from Serbia, though he used an old Yugoslavian passport—and Livia Pilisi, of Hungary. Wootten had never heard of them, but he ordered staff to cut them off and hightailed it to the Ritz. By the time he arrived, the mysterious gamblers were gone.

The following day, Wootten came in early to investigate. He found no obvious sign that the roulette wheel or table had been tampered with. Watching the CCTV footage, he noted that Tosa and Marjanovic jumped up to place their bets a few seconds into each spin. They must have been using some sort of computer, he thought.

Wootten had tried to give a speech at an industry event a few years prior about the threat to casinos from [tiny, increasingly powerful computing devices](https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-01-31/inside-the-20-year-quest-to-build-computers-that-play-poker "Inside the 20-Year Quest to Build Computers That Play Poker"), capable of processing feats humans could only dream of. He was laughed off stage. Ridicule still ringing in his ears, he made it his business to learn everything he could about the subject.

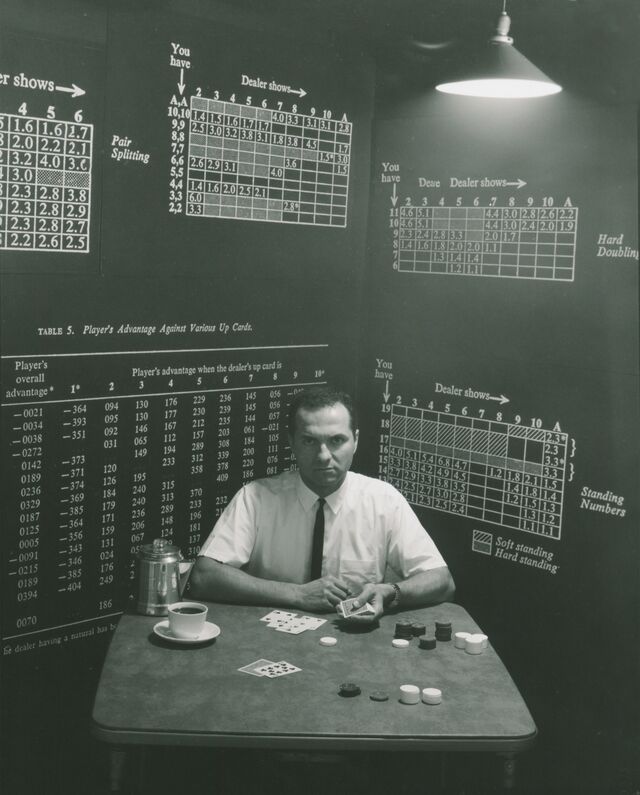

Thorp in 1964. Leigh Wiener

Computer-assisted roulette was born in the 1960s, the progeny of rebellious academics at elite American universities. If scientists armed with microprocessors could predict the movement of the stars and planets, why not roulette? It was a matter of physics. Edward Thorp, an [American mathematician and gambling pioneer](http://www.edwardothorp.com/ "Edward O. Thorp"), made the first serious attempt, along with Claude Shannon, the MIT professor who more or less invented information theory. From their point of view, roulette wasn’t totally random. It was a spherical object traversing a circular path, subject to the effects of gravity, friction, air resistance and centripetal force. An equation could make sense of those.

Modeling got tougher, though, once the ball moved in from the outer rim to the spinning central rotor, ricocheting off the metal slats and the sides of the numbered pocket dividers—a second, chaotic phase that scientific consensus held would scramble any prediction. Thorp and Shannon discovered, however, that by timing the speed of the ball and the rotor, they could calculate the ball’s likely destination. There were errors, but Thorp was delighted to find that their predictions were normally off by only a few pockets.

A schematic for a roulette wheel and wearable computer, from Thorp’s papers. Edward O. Thorp Papers/Courtesy University of California, Irvine Special Collections and Archives

An electrical diagram for a roulette device. Edward O. Thorp Papers/Courtesy University of California, Irvine Special Collections and Archives

To run their equation, the two mathematicians built and programmed the world’s first wearable computer, a matchbox-size gadget wired to a timing switch hidden inside a shoe. Once Thorp had calibrated the device to adjust to a specific wheel’s dynamics, all he had to do was tap his foot twice to get speed readings. The system worked, at least in a laboratory setting—their Sixties-era wiring kept fritzing out when they tried it in a casino.

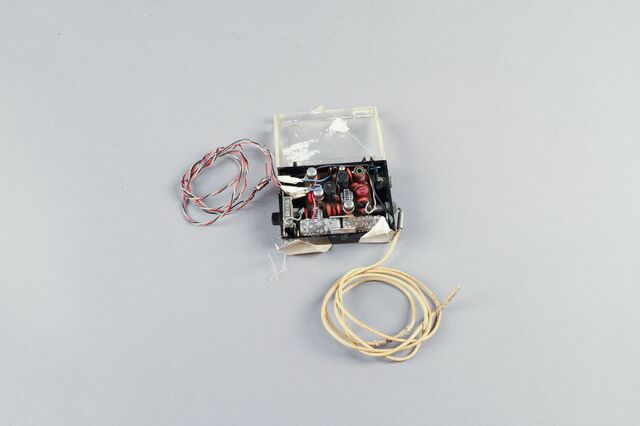

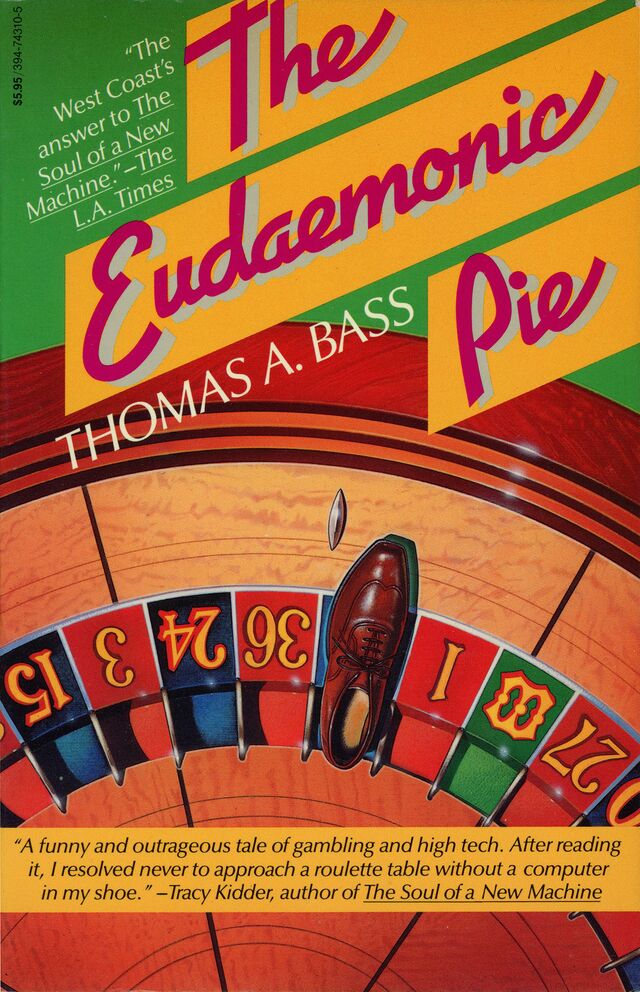

A decade later, J. Doyne Farmer, a physics student at the University of California at Santa Cruz, took up the challenge. Farmer dreamed of creating a utopian community of hippie inventors funded by gambling profits. He and his partners called their venture Eudaemonic Enterprises, after Aristotle’s term for the fulfilling sensation of a life well lived. Like Thorp before him, Farmer learned that roulette was more predictable than anyone imagined, and also that making the science work amid the sweat and noise of a real casino was almost impossible. His device used a hidden buzzer that told the wearer which of eight sections, or “octants,” the ball would likely drop into. At field tests in Lake Tahoe and Las Vegas casinos, the computer shorted out or overheated, zapping the wearer or burning their skin. The Eudaemons wasted several years and thousands of dollars before abandoning the project in the early 1980s. One of them published a book about their adventures called *The Eudaemonic Pie*. In the end, the book concluded, Eudaemonia wasn’t a goal to be attained, but a journey.

A wearable roulette computer developed by Shannon and Thorp. MIT Museum

*The Eudaemonic Pie*, published in 1985.

Wootten had read *The Eudaemonic Pie*, and he knew how far computers had advanced since its publication. As he considered Tosa’s method the day after the big Ritz score, he concluded that the six-second pause before the Croatian placed his bets was enough time to clock rotations of the ball and wheel and have a computer produce a forecast. He decided to call the cops.

Tosa, Marjanovic and Pilisi returned to the Ritz at 10 that night, as promised. This time they were led to a private room where a squad from the London Metropolitan Police was waiting. An officer politely informed them they were under arrest on suspicion of “deception” and led them away to be interviewed at a nearby police station. Once the gamblers were out of earshot, Wootten urged the cops to check their shoes and clothes for hidden devices.

Tosa and his companions reacted to being arrested with the same surreal calm they’d shown at the roulette wheel. At the station, they were interviewed separately through an interpreter. Tosa was robotically unhelpful, declining to answer questions. Marjanovic was more talkative but just as confounding. He claimed to be a professional gambler of such skill at roulette that he could win 70% of the time. Only “self-discipline” limited his profits, he said. Both denied using any kind of computer.

Pilisi, who seemed to be romantically involved with Marjanovic, was vague about how she knew Tosa and said she knew little about her partner’s gambling. A detective tried showing her CCTV footage of Marjanovic playing at the Ritz. “That’s your boyfriend winning half a million pounds,” he said, gesturing at the screen. “It’s like winning the lottery. You don’t show any emotion.” Pilisi shrugged. “So what?” she replied.

The police had seized four cellphones and a PalmPilot-type device, which were taken away to be analyzed. Searching the group’s hotel rooms, officers found several hundred thousand pounds and a list of casinos marked with symbols: ticks, crosses, pluses and minuses. The detective told Wootten that, given the sums in question, the Met’s money laundering division would be taking over. In the meantime, the force authorized the Ritz to halt payment on Tosa and Marjanovic’s checks, so they couldn’t take the casino’s money and flee.

Later that same evening, out on bail, Tosa, Marjanovic and Pilisi stopped outside the casino and had a brief, bizarre conversation with a doorman who later reported it to his superiors. Tosa told the doorman in Balkan-accented English that the Ritz’s owners were bad people who were looking for an excuse not to pay. He and his companions were going to sue to get their money, he warned.

About six months later, a chauffeured Mercedes-Benz pulled up outside the [Colony Club](https://www.thecolonyclub.co.uk/ "The Colony Club") casino, not far from the Ritz, and deposited two men who said they could prove it was possible to win at roulette without cheating.

The police investigation had stalled. Despite numerous searches, they hadn’t found earpieces, wiring or timers. Police IT specialists had found evidence of data being deleted from the seized cellphones—suspiciously, some felt—but no sign of any roulette-beating software.

Tosa and the other suspects had lawyered up and were refusing to answer any more questions. Instead, their attorney suggested, police should watch a demonstration showing how someone could conquer roulette without resorting to fraud. An executive at the Colony Club agreed to host and invited security chiefs from across the West End gambling scene.

Tosa himself wouldn’t take part. Instead, the attorney put forth a grim-faced Croatian named Ratomir Jovanovic to give the demonstration alongside his Lebanese playing partner, Youssef Fadel. The two had made approximately £380,000 playing roulette at various London venues around the same time as Tosa, using the same distinctive late-betting style. Police already suspected, though they couldn’t prove it, that Jovanovic was part of a gambling syndicate run by Tosa. Jovanovic’s presence at the demo seemed to confirm their theory.

When Jovanovic and Fadel arrived at the Colony, they were led to a private roulette chamber to find not only police, as they’d expected, but also half a dozen casino security bosses in dark suits. Most were former soldiers like Wootten, some had visible scars or warped knuckles, and all looked hostile. Fadel’s smile vanished. Jovanovic tried to bolt, but one of the casino guys kicked the door shut with his heel. “You’re not going anywhere,” he said, according to several attendees.

Wootten watched, gripped, as Jovanovic took his place at the cream-colored leather fringe of a roulette table. The Croatian’s method was recognizable from footage of Tosa at the Ritz: the pause, the wager, the spread of chips. Like Tosa, he used the area of the betting felt set aside for wagering swiftly on segments of the wheel, where he could cover five adjacent pockets with a single chip on the “neighbors” section.

But Jovanovic couldn’t make it work. He didn’t hit anything for the first few spins and barely improved from there. A casino executive started mouthing off about them wasting his time. The Croatian blamed bad vibes in the room for messing with his instincts. “We have heart for roulette,” he said. “We’ve lost our hearts.” Wootten didn’t buy it. How could this be any more stressful than playing live, with real money?

The police detective intervened to explain that everyone suspected the gamblers of using a hidden computer. We’re not doing that, Jovanovic offered. “We can play naked,” he said. At this, one of the casino representatives grabbed at the Croatian’s jacket as if to strip him. “Go on, then!” The detective had seen enough and ended the demonstration before things could turn ugly. He escorted the gamblers out.

To a cop’s eyes, Tosa and his gang still looked like criminals. They had large sums of cash, burner cellphones and passports showing travel to Angola and Kazakhstan. What exactly was their crime, though? Even if it could be proven that they’d used a computer, the answer wouldn’t have been clear. Nevada had banned the use of electronic devices in casinos back in the 1980s, but the UK had no such prohibition. The country’s gaming statute, which dated to 1845, was created to stop noblemen from blowing their family fortunes at West End clubs. It didn’t mention computers.

Not long after the Colony demo, the police phoned Wootten to say they wouldn’t be pressing charges against Tosa, Marjanovic or Pilisi, or continuing the investigation into Jovanovic and Fadel. Detectives hadn’t found any evidence of dishonesty or cheating, nor had they been able to establish a definitive link between the two groups.

Wootten was aghast. He imagined having to tell the casino’s billionaire owners, a conversation he’d been hoping to avoid. Was there any legal way to stop Tosa and the others from collecting their winnings? he asked. No, the officer said. There was no other option. The Ritz would have to pay up.

Photo Illustration by Irene Suosalo; Video: Getty Images

Wootten was determined not to let Tosa’s victory be the end of the matter, and he wasn’t the only one. Wootten’s friend Mike Barnett—once an electrician, then a professional gambler, then a high-paid casino security consultant—had been helping the Ritz and the Metropolitan Police understand how predictive roulette worked. The casino had paid for Barnett to fly in from Australia in the middle of the Tosa investigation, bringing along his own roulette timers and predictive software. He couldn’t be sure Tosa had used computers, but it was nevertheless an opportunity to convince skeptical cops and staff that roulette prediction wasn’t a myth.

In presentations that were seen by representatives of virtually every major casino group in the UK, as well as the national regulator, the [Gambling Commission](https://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/ "UK Gambling Commission"), Barnett invited audiences to try using a handheld clicker to time video footage of a moving wheel and ball precisely enough for the computer program to work its magic. Most could, and once they’d done it themselves, some of the mystery fell away. “To make money in roulette, all you need to do is rule out two numbers,” Barnett liked to say, flashing a gold Rolex and diamond encrusted ring as he held up his fingers. With two numbers eliminated, the odds became slightly better than even, flipping the house’s slender advantage.

The Gambling Commission ordered a government laboratory to test Barnett’s system. The lab confirmed his thesis: Roulette computers *did* work, as long as certain conditions were present.

Those conditions are, in effect, imperfections of one sort or another. On a perfect wheel, the ball would always fall in a random way. But over time, wheels develop flaws, which turn into patterns. A wheel that’s even marginally tilted could develop what Barnett called a “drop zone.” When the tilt forces the ball to climb a slope, the ball decelerates and falls from the outer rim at the same spot on almost every spin. A similar thing can happen on equipment worn from repeated use, or if a croupier’s hand lotion has left residue, or for a dizzying number of other reasons. A drop zone is the Achilles’ heel of roulette. That morsel of predictability is enough for software to overcome the random skidding and bouncing that happens after the drop. The Gambling Commission’s research on Barnett’s device confirmed it.

[The government’s report](https://www.roulettephysics.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/roulette-problem2.pdf "Roulette Wheel Testing report [pdf]") wasn’t released publicly after it was finished in September 2005; casinos made sure of that. But among industry figures, it gave an official imprimatur to a once-fanciful idea. The study also offered recommendations for how casinos could fight back: Shallower wheels. Smooth, low metal dividers between the number pockets. Or no dividers at all, only scalloped grooves for the ball to settle into. These design features increased the time a ball spent in the hard-to-predict second phase of its orbit, hopping around the pockets in such chaotic fashion that even a supercomputer couldn’t work out where it was headed.

Most important, roulette wheels had to be balanced with extraordinary precision. A quick check with a level was no longer enough. Even a fraction of one degree off, and the ball might end up in Barnett’s drop zone.

London casinos were some of the first to order new equipment to meet the specifications. The Ritz changed all its wheels within months. Word spread quickly. At an industry event in Las Vegas, Barnett asked an audience of gambling executives how many thought it was possible to predict roulette. Hardly anyone raised a hand. By the end of his presentation, when he asked again, almost everyone did.

As the gaming industry began taking the threat more seriously, wheels were developed with laser sensors and built-in inclinometers to detect even a hair’s breadth of tilt. The stakes were rising, as [gambling moved online](https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-08-04/twitch-s-gambling-boom-is-luring-gamers-into-crypto-casinos "Twitch’s Gambling Boom Is Luring Gamers Into Crypto Casinos") and millions of people around the world [began to wager on livestreams](https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2009-08-24/netplay-pushes-tv-roulette-as-broadcasters-seek-revenue-sources "Netplay Pushes TV Roulette as Broadcasters Seek Revenue Sources") from their home computers or cellphones.

One of the biggest livestreamers was Evolution Gaming Group. Founded in 2006 with some casino equipment and a small office in Latvia, the company charged betting firms a percentage of revenue to use its platform, which became a wildly lucrative niche. About a decade ago, according to several former employees, Evolution staff made a strange discovery. A handful of players were winning at statistically absurd rates on the roulette wheels spinning day and night at its facility in Riga. Engineers investigated and pinpointed a culprit: the floor. Specifically, there was a gap between its solid concrete base and the carpeted playing surface laid down just above, a standard feature in studios where audio is recorded. When a croupier stood next to the televised table, the floor flexed ever so slightly, not enough to catch the human eye but tilting enough to help anyone using prediction software. One online user won tens of thousands of dollars from a major Evolution partner before engineers installed platforms to steady the wheels.

As Evolution grew, opening outlets in Belgium, Malta and Spain, so did the ingenuity of the players exploiting any flaw in its operations. One gambling brand’s croupiers worked in a hot room cooled by a fan that Evolution found altered the movement of the ball. Brand-new equipment might arrive with unglued pockets or start to degrade and lose its randomness after only a few weeks of round-the-clock use. Sometimes, wheels got so dependable that gamblers didn’t even need a predictive equation. They could simply bet the favored section over and over. Always, there were players who seemed able to spot the imperfections before Evolution’s analysts could.

In response, Evolution hired an army of “game integrity” specialists and paid a fortune to consultants, including Barnett. The company developed software to track wheels in real time and identify whether any section was winning more than statistical models said it should. It gave croupiers a screen telling them to toss the ball more quickly or slowly, as required. By 2016, Evolution employed 400 people in its game integrity and risk department, according to an [annual report](https://evolution-com-media.s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/651419_0.pdf "Evolution Gaming annual report 2016 [pdf]") in which it also warned that its adversaries were getting more sophisticated with every passing year. (Asked for comment, a company spokesman said, “Evolution works hard to protect game integrity and it is a prerequisite for our business.”)

According to Barnett, there’s a new generation of online roulette sharps who no longer need human-operated switches to time the ball and wheel. Instead, they deploy software that scans the video feed and does it for them, all from a home computer with no security guards in sight. Gambling firms are fighting back with innovations like random rotor speed, or RRS, technology, using software to algorithmically slow the wheel differently on each spin.

There’s one surefire way casinos could stop prediction: calling “no more bets” before the ball is in motion. But they won’t. That would cut into profits by limiting the amount of play and deterring casual gamblers. Instead, the industry seems willing to pay a toll to a select few who know the secret, while trying to design out the flaws that make the game vulnerable. Walk into a casino anywhere in the world today. Look at the depth of the pockets, the height of the wheelhead, the curvature of the bowl, and you can see how Tosa and his counterparts have reshaped roulette.

John Wootten never forgot Niko Tosa. Part of him admired the Croatian, who was a cut above the grubby casino cheats he was accustomed to dealing with. If anything, Tosa helped Wootten’s career. He traveled the world to talk about the Ritz case, giving speeches in Macau, Las Vegas and Tasmania. Every so often, he was thrilled to get word of Tosa’s whereabouts from someone in his global network.

As the years went on, Tosa adopted different aliases, complete with fake IDs, and switched up his playing partners. But the piercing gaze, the long beak of a nose, were unmistakable. There he was at a Romanian casino in 2010, captured by a security camera with his hand stuffed into a trouser pocket (where, staff assumed, he must be hiding something). There he was again, in London, trying to get into a club in an unconvincing gray wig. Then Poland. Then Slovakia.

In 2013 the furious owner of a casino in Nairobi contacted Wootten about a Croatian who’d won 5 million Kenyan shillings ($57,000) playing roulette. The gambler would watch the wheel for a few seconds, then place neighbors bets. When challenged, he acted as if he was “expecting a confrontation,” the casino owner wrote in an email. Could it be the same Croatian who’d hit the Ritz almost a decade earlier?

When Wootten confirmed the man was one and the same, the casino owner phoned and said he’d contacted friends in the Kenyan government who he hoped could have Tosa arrested. Wootten wished him luck and hung up. He took the incident as a sign the gaming industry’s defensive measures were working. Tosa must be getting desperate, having to travel to Africa to find vulnerable wheels. There were casinos far from London where, Wootten knew, they wouldn’t hesitate to break a suspected cheat’s fingers.

Wootten outside his shed in London. Carlotta Cardana for Bloomberg Businessweek

Wootten retired in 2020, after the Ritz shut its doors permanently during the Covid-19 pandemic. Over the years he’d collected a cabinet full of increasingly ingenious devices: PalmPilots, reprogrammed cellphones, flesh-colored earpieces, miniature buttons and cameras. He knew of one player who’d hidden a roulette timer in his mouth and had heard rumors of another who’d tried to get a microprocessor surgically embedded in his scalp.

Yet Tosa had never been caught with so much as a thumb drive. Could it really be, Wootten wondered, that the man who’d done more than anyone to raise the alarm about computer roulette hadn’t actually used one?

He knew, too, that some of the early pioneers of the field had observed a curious phenomenon. After using predictive technology thousands of times, they’d developed a sense of where the ball would land, even without the computer. “It’s like an athlete,” Mark Billings, a lifelong player and author of *[Follow the Bouncing Ball: Silicon vs Roulette](https://www.amazon.com/Follow-Bouncing-Ball-Silicon-Roulette-ebook/dp/B08P91LXTM/ref=sr_1_2 "Follow the Bouncing Ball: Silicon vs Roulette on Amazon.com")*, said in an interview. “At some point all this stuff comes together. You look at the wheel. You just know.” Casinos call it “cerebral” clocking. All that’s needed is a drop zone and a potent, well-trained mind.

Wootten and Barnett debate the point to this day. A roulette computer was a neat explanation for casino staff, who didn’t want to look too closely at their shoddy equipment, and for Wootten, who wanted to prove a point to all the executives who’d laughed at him. But when I spoke to Barnett, he argued that the wheel at the Ritz was so old and predictable that Tosa wouldn’t have needed a computer to defeat it. “Blind Freddie could beat the wheel they played,” he said.

Back then, he’d wanted to believe, too. “I wanted to ride into Scotland Yard on my white horse and expose the M.O.,” he recalled. “The problem was there was not the slightest shred of evidence.”

Without that, Barnett said, there was only one thing left to do: “The only way we’ll really know is if you talk to Niko.”

I figured Tosa would be hard to track down. He’s spent most of his career trying not to be found. Sure enough, there was no record of him in company or property registries, or in news reports or on social media. I managed to get hold of a list of his playing partners and worked my way through it, but they all turned into dead ends.

Business associates of his Ritz companions, Pilisi and Marjanovic, ignored calls and emails and blocked my number when I texted. I did find one Serbian businessman who seemed to know them both, but he said he’d lost touch years ago and was trying to find them himself. When pressed, he grew irate. “What part don’t you understand?” he asked.

I thought I’d caught a break when one of Tosa’s more recent partners listed an address near my home in West London, but the man’s ex-wife answered the door and said he’d moved back to Montenegro when they separated. So it went.

Eventually, I realized the different addresses Tosa had given casinos over the years were clustered along the same stretch of Croatian coast, south of Dubrovnik. They were tiny villages, mostly. I hoped someone might have heard of him, so I sent a colleague to ask around. After striking out a few times, he found a former neighbor and showed him Tosa’s photograph. He has a holiday villa nearby, the neighbor said, just up the road from the local convenience store. Try him there.

My colleague found Tosa outside the house, working on an SUV. He was friendly enough, though he said he didn’t talk to reporters. He offered a phone number but didn’t answer it the numerous times I called.

In November, I flew to Dubrovnik, the picturesque medieval fort city that was one of the [main backdrops](https://www.kingslandingdubrovnik.com/ "King's Landing Dubrovnik") for *Game of Thrones*. The day I arrived, a storm blew in off the Adriatic, slamming sheets of rain against the cliffs and sending the few off-season tourists scurrying for their hotels. Tosa’s villa was an hour’s drive down a winding coastal road. There was a solid iron gate blocking the entrance to his front door and no one home, so I folded a note into a plastic folder to keep out the rain and slid it under the gate.

A village in the region of Croatia where Tosa is from. Kit Chellel

The town’s only cafe was open and full of chain-smoking locals in sweatsuits. It was an unpretentious place decorated with *Godfather* posters. I ordered a coffee and struck up a conversation with the barman. Did he know that probably the world’s most successful roulette player had a place around the corner? No, he said—he never gambled. He thought it was a good way to lose money.

I showed him a picture of Tosa. He said he didn’t recognize the man, though he was curious how I’d found the photo. After a while, I left a tip, said goodbye and walked off, defeated, in the direction of my car. The barman came running out into the downpour. “I just called him,” he said. “He is my good friend. I wanted to check with him first. He is in Dubrovnik.” Tosa phoned me a few hours later, and we arranged to meet at a fish restaurant in the old harbor.

In person, he was even taller and more birdlike than I’d expected. He spotted me in the street outside and pulled me into an awkward embrace under his umbrella, saying, “Oh oh oh oh.” Inside, he introduced me to a friend and a younger relative who both spoke good English and would translate when needed. Niko Tosa, they explained, wasn’t his real name. I agreed not to publish the actual one, because they said he had enemies who were less forgiving than John Wootten.

Tosa was by turns enigmatic, jovial, prickly, paranoid, frank. Also generous—he insisted on buying a round of single malt whiskies. He readily admitted to playing roulette using fake identity documents and to disguising himself with a wig and fake beard. “What’s wrong with that?” he asked. He had no problem referring to some of his former playing partners as criminals. One of them had been gunned down in Belgrade in 2018, killed in an apparent Balkan-mafia feud. Tosa had fallen out with others over money.

But he was adamant that he’d never used a roulette computer. The idea was like something from James Bond, he said with a laugh, adding, “We are peasants.” As I pressed him about computers, he threw up his hands in exasperation and started to argue with his friend. Is he angry, I asked. “No, that’s just how he talks,” the friend replied. “He’s asking how he can make you understand.”

I began to suspect that Tosa had agreed to talk to me specifically to make this point. Between glasses of white wine and plates of locally caught squid, he burst out, “You can call me Nikola Tesla if I have such a device!”

So how did Tosa do it, then? Practice, he said. They showed me a video clip of a glistening roulette wheel Tosa kept in his house to train his brain. How had he learned? A friend taught him—Ratomir Jovanovic, the Croatian who’d given the disastrous demonstration at the Colony Club. London police had been right that the two were working together.

The condition of the wheel is vital, Tosa said. That was why he’d sought out a particular table at the Ritz—he’d played the wheel enough to confirm that he could beat it. He’d been able to identify it on sight even after the casino moved it into the Carmen Room.

I think I believed him when he said he didn’t use a computer. Later on, for a sanity check, I contacted Doyne Farmer, the physicist whose roulette prediction exploits are chronicled in *The Eudaemonic Pie*. “I do think it’s conceivable that someone could do what we do without a computer, providing the wheel is tilted and the rotor is not moving too fast,” said Farmer, who’s [now a professor](http://www.doynefarmer.com/about-me "J. Doyne Farmer") at the University of Oxford. He compared cerebral clocking to musical talent, suggesting it might activate similar parts of the brain, those dedicated to sound and rhythm.

Then again, if Tosa had concealed a tiny contraption, I don’t think he’d have told me. It seemed to me an uncomfortable life, traveling the world in search of casinos where he wouldn’t be recognized, waiting for security teams monitoring closed-circuit cameras to realize he was too good. Tosa said he’d been beaten up by casino thugs more than once. Sitting at the table in Dubrovnik, I asked him if he ever felt hunted. He looked baffled by the question. “Why would I?” The casinos were the prey; he was the hunter.

His young relative said he could remember the day, years back, when Tosa first pulled up in a Ferrari. Their hometown in the foothills of the Dinaric Alps isn’t rich by Croatian standards, though Tosa is from a prominent family. He seemed to share traits I’ve seen in other professional gamblers: an aversion to the grind of nine-to-five and a need to live on his own terms, whatever the risks. Ultimately, what set him apart from other roulette predictors was his willingness to go big. Most players only dare win a few thousand dollars at a time, for fear of being discovered. “Like squirrels,” Tosa said with contempt. If he hadn’t been arrested at the Ritz, he claimed, he would have gone back the next night and made £10 million. He felt the casino had gotten off lightly.

Toward the end of our encounter, Tosa asked exactly when my story would be published. Why did he want to know? He was planning his next international trip, he said, smiling. He didn’t want me to blow his cover. —*With Vladimir Otasevic, Daryna Krasnolutska, Peter Laca and Misha Savic*

*Read more: [The Gambler Who Cracked the Horse-Racing Code](https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2018-05-03/the-gambler-who-cracked-the-horse-racing-code)*

THE HORSE wasn’t just skinny, she was skeletal. Not just thirsty, desperate. Alive, but just barely.

When the scrawny filly wandered into Joey Ferris’ yard, he knew exactly where she had come from. Ferris was a lieutenant at the Mingo County Sheriff’s Office, where operators frequently fielded calls about horses like this. In addition to putting out food and water, he decided to use the opportunity to call attention to their ongoing plight.

He began the video he uploaded to YouTube in 2017 with a matter-of-fact assessment: “Bad things are happening in Southern West Virginia.”

“People get a horse,” Ferris says into the camera, eyebrows furrowed, “and they leave the horse on the strip mine.”

Behind him, the cumin-colored filly bowed toward a pan of water, her ombre tail flicking away dogged summer gnats. It had been a few weeks since this one had appeared on his property, he explained. Her ribs were once again beginning to disappear beneath her flesh, but the horse’s hip bones strained against her hide like a pair of blunt arrowheads. “We’ve been feeding her really good, but she’s still bony.”

Ferris posted the video to his YouTube channel and called it *Abandoned Horses of WV Need Help*. But Ferris was also in need of assistance. The bony brown horse was content to hang out in his backyard for a meal or two, but she bolted at the first sign of a harness. So he forwarded the video to someone who might know what to do.

If anyone knew that West Virginia’s abandoned horses needed help, it was Tinia Creamer, who had been trying to get people to pay attention to the problem for years—in blog posts, presentations to politicians, and YouTube videos of her own. Creamer runs Heart of Phoenix, a West Virginia horse rescue about two hours north of Ferris’s home in the area known as the Southern Coalfields, where decades of strip-mining – removing mountaintops to access the minerals beneath – have turned the undulating topography into flat, grassy prairies ideal for grazing. The consolation prize: for years, locals took advantage of the newly available space.

It was an informal system with implicit rules: Round up your horses in the winter, absolutely no stallions. But when the economy tanked in 2008, many in the region could no longer afford to feed their horses. And so they simply left them—even their stallions—on these sites, hopeful they would survive on the grass that mining companies were legally obligated to plant after operations had shut down.

> “People get a horse and they leave the horse on the strip mine.”

>

> Joey Ferris, Mingo County Sheriff’s Office

Within a decade, thousands of free-roaming horses were scratching out a living on abandoned and active strip mines across nine counties in Eastern Kentucky and four in southern West Virginia, while disagreements over the scope of the problem and how to solve it intensified. Some, like Creamer, maintained the horses were ill-equipped for the elements and needed to be removed. Others argued that all the horses needed was a little supplemental care—a salt block here, a hay bale there—and not only could they endure, they might actually become a point of pride for the region. Something beautiful in a beleaguered place.

Meanwhile, more horses were turned out. More horses were born. More horses died.

About a year before Creamer heard from Ferris, her organization responded to a call about another strip mine horse in need. The horse eventually known as Revenant was a deep chestnut with white feet, the front left of which hung uselessly, gruesomely fused in the shape of a hockey stick. His injury was old, perhaps caused by an encounter with a mine shaft or a collision with heavy machinery. Rejected by his herd, the horse had somehow dragged himself across the mountain to find food and water.

“It is beyond our scope of understanding how he is alive,” Creamer [later wrote](https://heartofphoenix.org/2016/03/12/revenant-a-mine-horse-with-a-destroyed-front-leg-from-west-virginia-heart-of-phoenix-equine-rescue/) of Revenant, his body thin and misshapen; it was hardly a question that he be euthanized.

But when Creamer watched Ferris’s video of the filly who would be named Phoebe, she knew this rescue would go differently. “A starving horse two weeks from death,” Creamer says, but young. “Age was greatly on her side.”

Creamer figured that, like Revenant, Phoebe had also been rejected by her herd. At some point—perhaps weakened by parasites or too dependent on her mother’s milk—she had become a liability. Coyote bait. To drive her away, the other horses kicked her, bit her, or ran her down until the only logical thing for the filly to do was seclude herself.