"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Adam Sandler doesn’t need your respect. But he’s getting it anyway..md\"> Adam Sandler doesn’t need your respect. But he’s getting it anyway. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Brilliant Inventor Who Made Two of History’s Biggest Mistakes.md\"> The Brilliant Inventor Who Made Two of History’s Biggest Mistakes </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/How an FBI agent stained an NCAA basketball corruption probe - Los Angeles Times.md\"> How an FBI agent stained an NCAA basketball corruption probe - Los Angeles Times </a>",

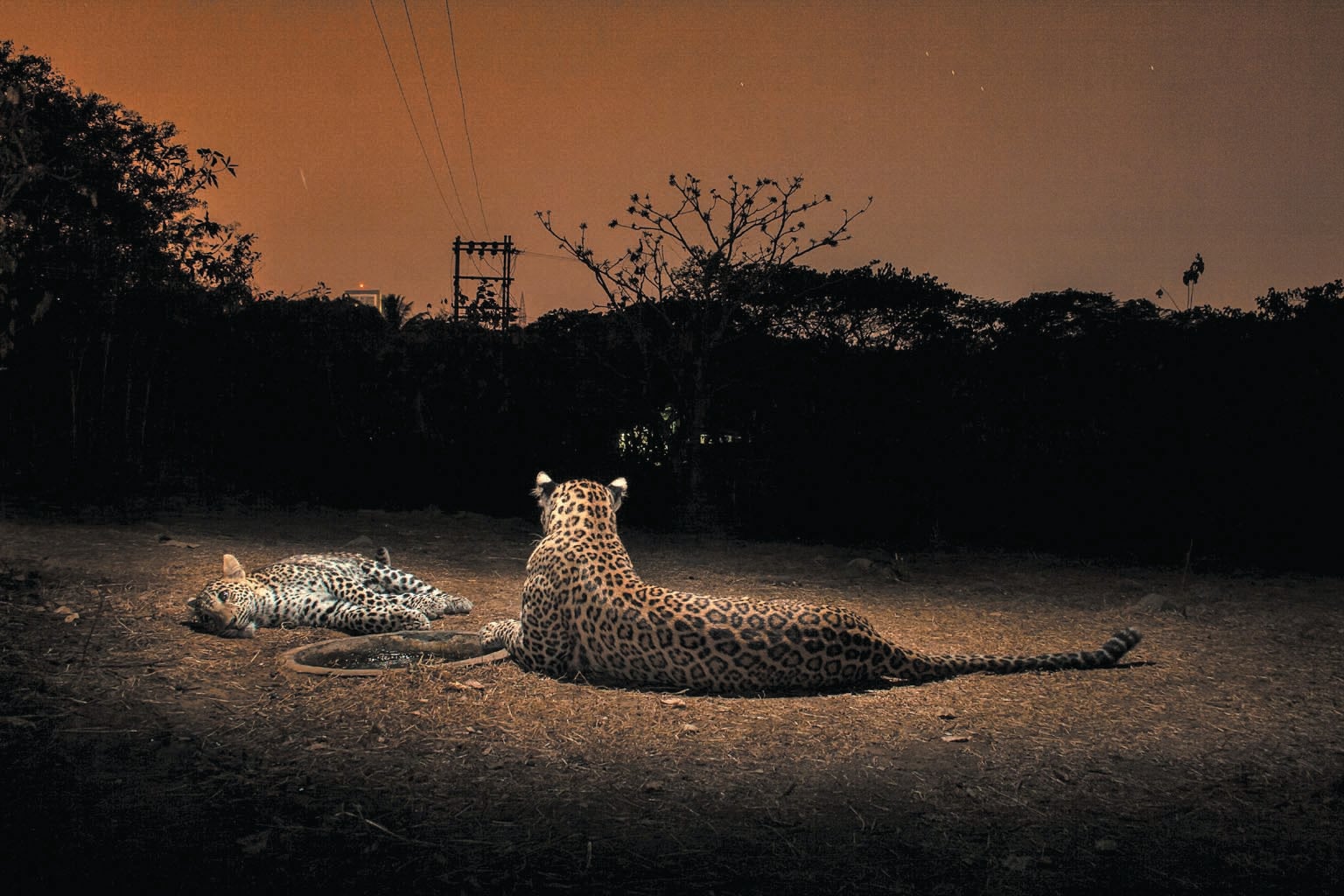

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Leopards Are Living among People. And That Could Save the Species.md\"> Leopards Are Living among People. And That Could Save the Species </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Why Joe Biden’s Honeymoon With Progressives Is Coming to an End.md\"> Why Joe Biden’s Honeymoon With Progressives Is Coming to an End </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Striking French workers dispute that they want a right to ‘laziness’.md\"> Striking French workers dispute that they want a right to ‘laziness’ </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Les Combrailles, à la découverte de l’Auvergne secrète.md\"> Les Combrailles, à la découverte de l’Auvergne secrète </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Law Roach on Why He Retired From Celebrity Fashion Styling.md\"> Law Roach on Why He Retired From Celebrity Fashion Styling </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Is Fox News Really Doomed.md\"> Is Fox News Really Doomed </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The One Big Question Bernie Sanders Won’t Answer.md\"> The One Big Question Bernie Sanders Won’t Answer </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The One Big Question Bernie Sanders Won’t Answer.md\"> The One Big Question Bernie Sanders Won’t Answer </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Humans Started Riding Horses 5,000 Years Ago, New Evidence Suggests.md\"> Humans Started Riding Horses 5,000 Years Ago, New Evidence Suggests </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/US-China 1MDB Scandal Pits FBI Against Former Fugee Pras Michel.md\"> US-China 1MDB Scandal Pits FBI Against Former Fugee Pras Michel </a>"

],

],

"Renamed":[

"Renamed":[

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.03 Food & Wine/Brown Butter Farro with Mushrooms & Burrata.md\"> Brown Butter Farro with Mushrooms & Burrata </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.03 Food & Wine/Brown Butter Farro with Mushrooms & Burrata - T Dish.md\"> Brown Butter Farro with Mushrooms & Burrata - T Dish </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.04 Cinematheque/The Dark Knight Rises (2012).md\"> The Dark Knight Rises (2012) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Adam Sandler doesn’t need your respect. But he’s getting it anyway..md\"> Adam Sandler doesn’t need your respect. But he’s getting it anyway. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Brilliant Inventor Who Made Two of History’s Biggest Mistakes.md\"> The Brilliant Inventor Who Made Two of History’s Biggest Mistakes </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How an FBI agent stained an NCAA basketball corruption probe - Los Angeles Times.md\"> How an FBI agent stained an NCAA basketball corruption probe - Los Angeles Times </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Leopards Are Living among People. And That Could Save the Species.md\"> Leopards Are Living among People. And That Could Save the Species </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Why Joe Biden’s Honeymoon With Progressives Is Coming to an End.md\"> Why Joe Biden’s Honeymoon With Progressives Is Coming to an End </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Striking French workers dispute that they want a right to ‘laziness’.md\"> Striking French workers dispute that they want a right to ‘laziness’ </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Law Roach on Why He Retired From Celebrity Fashion Styling.md\"> Law Roach on Why He Retired From Celebrity Fashion Styling </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Is Fox News Really Doomed.md\"> Is Fox News Really Doomed </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Le Camp des Saints.md\"> Le Camp des Saints </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Le Camp des Saints.md\"> Le Camp des Saints </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Camp of the Saints.md\"> The Camp of the Saints </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Camp of the Saints.md\"> The Camp of the Saints </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.01 Reading list/The Power And The Glory.md\"> The Power And The Glory </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.01 Reading list/The Power And The Glory.md\"> The Power And The Glory </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"01.02 Home/Sport.md\"> Sport </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/US-China 1MDB Scandal Pits FBI Against Former Fugee Pras Michel.md\"> US-China 1MDB Scandal Pits FBI Against Former Fugee Pras Michel </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Adam Sandler doesn’t need your respect. But he’s getting it anyway..md\"> Adam Sandler doesn’t need your respect. But he’s getting it anyway. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How an FBI agent stained an NCAA basketball corruption probe - Los Angeles Times.md\"> How an FBI agent stained an NCAA basketball corruption probe - Los Angeles Times </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Leopards Are Living among People. And That Could Save the Species.md\"> Leopards Are Living among People. And That Could Save the Species </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Why Joe Biden’s Honeymoon With Progressives Is Coming to an End.md\"> Why Joe Biden’s Honeymoon With Progressives Is Coming to an End </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Brilliant Inventor Who Made Two of History’s Biggest Mistakes.md\"> The Brilliant Inventor Who Made Two of History’s Biggest Mistakes </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Striking French workers dispute that they want a right to ‘laziness’.md\"> Striking French workers dispute that they want a right to ‘laziness’ </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Law Roach on Why He Retired From Celebrity Fashion Styling.md\"> Law Roach on Why He Retired From Celebrity Fashion Styling </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Is Fox News Really Doomed.md\"> Is Fox News Really Doomed </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Untold Story Of Notorious Influencer Andrew Tate.md\"> The Untold Story Of Notorious Influencer Andrew Tate </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Is Fox News Really Doomed.md\"> Is Fox News Really Doomed </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Au Revoir Là-Haut.md\"> Au Revoir Là-Haut </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Au Revoir Là-Haut.md\"> Au Revoir Là-Haut </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Le Temps gagné.md\"> Le Temps gagné </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Le Temps gagné.md\"> Le Temps gagné </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Camp of the Saints - 2017.md\"> The Camp of the Saints - 2017 </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Camp of the Saints - 2017.md\"> The Camp of the Saints - 2017 </a>",

@ -9157,24 +9294,7 @@

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/US-China 1MDB Scandal Pits FBI Against Former Fugee Pras Michel.md\"> US-China 1MDB Scandal Pits FBI Against Former Fugee Pras Michel </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/US-China 1MDB Scandal Pits FBI Against Former Fugee Pras Michel.md\"> US-China 1MDB Scandal Pits FBI Against Former Fugee Pras Michel </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How the Biggest Fraud in German History Unravelled.md\"> How the Biggest Fraud in German History Unravelled </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How the Biggest Fraud in German History Unravelled.md\"> How the Biggest Fraud in German History Unravelled </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/EVT Will Save Millions of Lives From Stroke. Eventually..md\"> EVT Will Save Millions of Lives From Stroke. Eventually. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/EVT Will Save Millions of Lives From Stroke. Eventually..md\"> EVT Will Save Millions of Lives From Stroke. Eventually. </a>"

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Say Nothing.md\"> Say Nothing </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"02.02 Paris/Andy Wahlou.md\"> Andy Wahlou </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"02.02 Paris/Le Ballroom du Beef Club.md\"> Le Ballroom du Beef Club </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"02.03 Zürich/Pile of Books.md\"> Pile of Books </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"02.03 Zürich/Pile of Books.md\"> Pile of Books </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Ian Fishback’s American Nightmare.md\"> Ian Fishback’s American Nightmare </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Dystopian Underworld of South Africa’s Illegal Gold Mines.md\"> The Dystopian Underworld of South Africa’s Illegal Gold Mines </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Great Dumpling Drama of Glendale, California.md\"> The Great Dumpling Drama of Glendale, California </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Secret Weapons of Ukraine.md\"> The Secret Weapons of Ukraine </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Tragedy of the Spice King.md\"> The Tragedy of the Spice King </a>"

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Les Combrailles, à la découverte de l’Auvergne secrète.md\"> Les Combrailles, à la découverte de l’Auvergne secrète </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Mail Import.md\"> Mail Import </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Mail Import.md\"> Mail Import </a>"

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Rich text.md\"> Rich text </a>"

],

],

"Linked":[

"Linked":[

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Bull elephants – their importance as individuals in elephant societies - Africa Geographic.md\"> Bull elephants – their importance as individuals in elephant societies - Africa Geographic </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How a civil war erupted at Fox News after the 2020 election.md\"> How a civil war erupted at Fox News after the 2020 election </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The One Big Question Bernie Sanders Won’t Answer.md\"> The One Big Question Bernie Sanders Won’t Answer </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Camp of the Saints - 2017.md\"> The Camp of the Saints - 2017 </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Law Roach on Why He Retired From Celebrity Fashion Styling.md\"> Law Roach on Why He Retired From Celebrity Fashion Styling </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Why Joe Biden’s Honeymoon With Progressives Is Coming to an End.md\"> Why Joe Biden’s Honeymoon With Progressives Is Coming to an End </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.01 Reading list/The Power And The Glory.md\"> The Power And The Glory </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Purposeful Presence of Lance Reddick.md\"> The Purposeful Presence of Lance Reddick </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Leopards Are Living among People. And That Could Save the Species.md\"> Leopards Are Living among People. And That Could Save the Species </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.04 Cinematheque/John Wick (2014).md\"> John Wick (2014) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Adam Sandler doesn’t need your respect. But he’s getting it anyway..md\"> Adam Sandler doesn’t need your respect. But he’s getting it anyway. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How an FBI agent stained an NCAA basketball corruption probe - Los Angeles Times.md\"> How an FBI agent stained an NCAA basketball corruption probe - Los Angeles Times </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Leopards Are Living among People. And That Could Save the Species.md\"> Leopards Are Living among People. And That Could Save the Species </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Why Joe Biden’s Honeymoon With Progressives Is Coming to an End.md\"> Why Joe Biden’s Honeymoon With Progressives Is Coming to an End </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Bull elephants – their importance as individuals in elephant societies - Africa Geographic.md\"> Bull elephants – their importance as individuals in elephant societies - Africa Geographic </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Brilliant Inventor Who Made Two of History’s Biggest Mistakes.md\"> The Brilliant Inventor Who Made Two of History’s Biggest Mistakes </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Silicon Valley Bank Contagion Is Just Beginning.md\"> The Silicon Valley Bank Contagion Is Just Beginning </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.04 Cinematheque/John Wick (2014).md\"> John Wick (2014) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.04 Cinematheque/Batman Begins (2005).md\"> Batman Begins (2005) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/An Icelandic Town Goes All Out to Save Baby Puffins.md\"> An Icelandic Town Goes All Out to Save Baby Puffins </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.04 Cinematheque/Batman Robin (1997).md\"> Batman Robin (1997) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Untold Story Of Notorious Influencer Andrew Tate.md\"> The Untold Story Of Notorious Influencer Andrew Tate </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.04 Cinematheque/Batman Forever (1995).md\"> Batman Forever (1995) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/How a civil war erupted at Fox News after the 2020 election.md\"> How a civil war erupted at Fox News after the 2020 election </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.04 Cinematheque/Batman (1989).md\"> Batman (1989) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Mel Brooks Isn’t Done Punching Up the History of the World.md\"> Mel Brooks Isn’t Done Punching Up the History of the World </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.04 Cinematheque/Batman Returns (1992).md\"> Batman Returns (1992) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The One Big Question Bernie Sanders Won’t Answer.md\"> The One Big Question Bernie Sanders Won’t Answer </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Humans Started Riding Horses 5,000 Years Ago, New Evidence Suggests.md\"> Humans Started Riding Horses 5,000 Years Ago, New Evidence Suggests </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.04 Cinematheque/Batman (1989).md\"> Batman (1989) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Life After Food.md\"> Life After Food </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.04 Cinematheque/Batman Robin (1997).md\"> Batman Robin (1997) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/On the Trail of the Fentanyl King.md\"> On the Trail of the Fentanyl King </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"03.04 Cinematheque/Batman Returns (1992).md\"> Batman Returns (1992) </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/On the Trail of the Fentanyl King.md\"> On the Trail of the Fentanyl King </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Is Fox News Really Doomed.md\"> Is Fox News Really Doomed </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/EVT Will Save Millions of Lives From Stroke. Eventually..md\"> EVT Will Save Millions of Lives From Stroke. Eventually. </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Striking French workers dispute that they want a right to ‘laziness’.md\"> Striking French workers dispute that they want a right to ‘laziness’ </a>"

],

],

"Removed Tags from":[

"Removed Tags from":[

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/‘Incredibly intelligent, highly elusive’ US faces new threat from Canadian ‘super pig’.md\"> ‘Incredibly intelligent, highly elusive’ US faces new threat from Canadian ‘super pig’ </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/‘Incredibly intelligent, highly elusive’ US faces new threat from Canadian ‘super pig’.md\"> ‘Incredibly intelligent, highly elusive’ US faces new threat from Canadian ‘super pig’ </a>",

{"id":"pdf-to-markdown-plugin","name":"PDF to Markdown","version":"0.0.7","description":"Save a PDF's text (headings, paragraphs, lists, etc.) to a Markdown file.","author":"Alexis Rondeau","authorUrl":"https://publish.obsidian.md/alexisrondeau","js":"main.js"}

# Adam Sandler doesn’t need your respect. But he’s getting it anyway.

Adam Sandler will be honored by the Kennedy Center with the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor. (Erik Carter for The Washington Post)

## In a rare sit-down interview, the former SNL star and comedy icon reflects on his career as he receives the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor

PITTSBURGH — During every Adam Sandler stand-up show, he straps on his electric guitar and sings a song. Unlike the bite-size ditties he’s peppered through the set about selfies or baggy shorts, this one concerns his late, great “Saturday Night Live” buddy, Chris Farley.

It is a perfect tribute. Sandler, singing softly as he strums in G, captures the complicated beauty of Farley as clips of his most memorable high jinks play on a giant screen behind him. The crowd roars as he references Farley’s electrifying SNL turns as a Chippendales dancer and a motivational speaker “living in a van down by the river.” There is a hush as Sandler slips into the bridge, a peek into his friend’s vulnerability.

*I saw him in the office, crying with his headphones on*

*Listening to a KC and the Sunshine Band song*

*I said, “Buddy, how the hell is that making you so sad?”*

*Then he laughed and said, “Just thinking about my dad”*

Sandler first performed “Farley” in 2015 during a guest spot at Carnegie Hall, a show that inspired him to return to doing stand-up tours. And he played it when he hosted SNL in 2019, choking up visibly.

“Only Sandler could do that,” says Dana Carvey, an SNL star when the younger comedian arrived in 1990. “That’s another gear that Adam has. He’ll be really, really silly. But he’s not afraid to go for sentimentality and earnestness.”

The song, with its mix of low- and highbrow, the profane and poetic, could serve as a four-minute-and-22-second window into why the comedian and actor is being recognized with the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor. And it’s why his friends are glad that, at 56, he’s finally getting his due. All of which may sound strange for someone whose films — generational comedies that include “Happy Gilmore,” “The Wedding Singer” and “Grown Ups” — have earned more than $3 billion at the box office. But for Sandler, popularity and praise have rarely come hand in hand.

That has changed some in recent years. Sandler’s dramatic acting performances in 2017’s “The Meyerowitz Stories,” last year’s basketball drama “Hustle” and especially 2019’s “Uncut Gems” brought unlikely (and ultimately fruitless) Oscar buzz. His 2019 stand-up special “100% Fresh” and 2020’s throwback comedy “Hubie Halloween” confirmed why he’s been packing movie theaters and arenas since the Clinton administration. The Twain puts Sandler in the company of such figures as Eddie Murphy, Carol Burnett and Steve Martin.

And the timing is perfect, says his old boss, Lorne Michaels, himself a recipient of the prize from the Kennedy Center in 2004.

“The nature of comedy is you get the audience, you get the money,” says Michaels, SNL’s creator and executive producer. “Respect is the last thing you get.”

###

‘Completely new and fresh’

Sandler’s Happy Madison Productions headquarters is in a small building in Pacific Palisades, not far from where he lives with his wife, Jackie, and their daughters, Sadie, 16, and Sunny, 14.

On a recent Friday afternoon, the bearded Sandler enters the room with a slight limp courtesy of hip replacement surgery he had in the fall. A few days earlier, he was in Boston, helping Sadie look at colleges. The next day he’ll go to the Nickelodeon Kids’ Choice Awards with his daughters who will watch him receive the King of Comedy Award and submit to the inevitable sliming. (Sandler is the first person to receive the top comedy honors from Nickelodeon and the Kennedy Center, let alone receive them in the same month.)

Sandler typically doesn’t do interviews like this. He will go on podcasts with buds, sit on the couch on “Jimmy Kimmel Live!” or answer goofy questions on “Entertainment Tonight” (“Who would be at *your* murder mystery party?”) but this — a three-hour drill-down about his career — is not his thing. He can tell you exactly why.

Flash back to 1995 in the SNL offices. Al Franken, the veteran writer and future senator, confronts Sandler and tells him that nobody appreciated his quotes in that TV Guide story. Huh? Sandler checks and sees that the magazine ran a quote from him complaining that “the writing sucks” on the show.

“I go, ‘I never f---in’ said that. I never would say that,’” he remembers now. “So I called the writer. I said, ‘Why did you say I said that?’ And he kind of didn’t want to talk to me. I should have taped the conversation.”

Then, a few months later, came the New York magazine article titled “[Comedy Isn’t Funny](https://nymag.com/arts/tv/features/47548/).” Michaels gave Chris Smith, a writer with the magazine, unfettered access to Studio 8H for weeks. The resulting article mashed the writer’s disgust for the show with anonymous quotes attacking its cast. The harshest mockery was reserved for the boyishly sensitive Farley.

“He came and fake buddied up with us,” says David Spade, who was also in the cast. “We let him in on all these meetings and dinners, and he wrote a s---ty piece to get himself notoriety.”

Asked about his article today, Smith says SNL “was not a happy place at the time.”

By then, Sandler had starred in “Billy Madison,” an instant entry into the teenage canon that debuted at No. 1 at the box office. It also got terrible reviews. *Terrible* reviews*.* It was one of the last times Sandler read what the critics had to say, good or bad.

“When ‘Billy Madison’ came out and I realized I’m going to be in the newspaper, that was a big deal,” he says. “When I was a kid, if I got a couple of hits in baseball and was [in the Union Leader](https://www.unionleader.com/sports/concord-outlasts-goffstown-for-state-little-league-title/article_8b8a6919-f218-5669-beff-61b3b0043e7d.html) — Adam Sandler, you know, shortstop got a single and a double — I got excited. And then I read a couple reviews and I was like, ‘Woof, that hurts.’ I thought they would have a good time with it like I did. And then ‘Happy Gilmore’ was getting trashed and my friends were getting all riled up, and I just said, ‘No, I don’t need to read that stuff.’”

Ultimately, Sandler would respond. Just not to the critics.

“I decided I wanted to talk through what I like to do,” he says. “I like to do my stand-up. I like to do my movies. I was just happy doing that.”

Sandler grew up in Manchester, N.H., the youngest of Judy and Stanley’s four children. They were supportive parents. Judy praised his singing, and the boy would sometimes entertain her by crooning Johnny Mathis from the back seat. Stanley, an electrical contractor, coached his sports teams and bought him an electric guitar at the age of 12. Sandler still takes that Strat out onstage. He named his character in 2022’s “Hustle” after Stanley, who died in 2003.

Growing up, Sandler played basketball for the local Jewish community center team and guitar in bands called Messiah, Spectrum and Storm. He also fell in love with comedy, listening to Steve Martin and Cheech & Chong records, watching “Caddyshack” and “Animal House,” and seeing Eddie Murphy on SNL.

He headed to New York University in 1984 to study acting and was setting up his room in Brittany Hall when Tim Herlihy walked in. Sandler told Herlihy he wanted to be a comedian. Herlihy told Sandler he wanted to study economics and get rich. That first weekend, though, he handed Sandler a few jokes he had scribbled down for him. He’s been a regular writing partner since, from 1995’s “Billy Madison” to “Hubie Halloween.” Elsewhere in the dorm, they met a business major, Jack Giarraputo, and his roommate, Frank Coraci, who was studying film. Another NYU acting student, Allen Covert, also joined the crew. All remain essential partners with the exception of Giarraputo, who left the business in 2014 to spend more time with his family.

Sandler did his first stand-up at 17 at an open mic in Boston. He didn’t realize you had to write material and remembers riffing about his family. At NYU, he became a club regular. At first, he struggled and sometimes even turned on the crowd, until some older comics told him yelling at the audience wasn’t a great strategy.

What he had going for him, even before he had great material, still works for him onstage. There is a natural ease and a likability. He will chuckle as he tells a joke, as if you’re playing pool or getting a burger and your buddy has a funny story to tell you.

“It’s not an affectation,” says Herlihy. “It’s the way his mind works. When he’s laughing, it’s like, ‘Oh, this is a good part.’ Like this guy who lived it can’t even get through it without laughing.”

“As a young person,” adds director Judd Apatow, who roomed with Sandler after NYU but before SNL, “everybody that encountered him thought, ‘This guy is going to be a gigantic star.’ Because he was making us so happy when we hung around with him.”

That personality captured Doug Herzog, then an MTV executive who would later launch “The Daily Show” and “South Park.” In 1987, Herzog had gone to a club to see another act as he scouted for MTV’s “Remote Control” game show. He ended up hiring Sandler, who was still living in his dorm.

“I’m waiting and this kid jumps onstage — sneakers, old-school sweatpants, end-of-the-’80s ratty T-shirt, backwards baseball hat,” says Herzog. “I would say an idiosyncratic kind of vibe and tone. You’re also, like, in the heyday of the Beastie Boys and I was like, ‘Oh, he kind of looks like a Beastie Boy and he’s funny and he’s charming.’”

Sandler’s biggest break came two years later. He and Chris Rock auditioned for SNL with a group of comics. Michaels remembers there were others in the room who were more versatile. But nobody as original.

“Most people audition in the style of things that have already been on the show,” Michaels says. “But what I’m looking for is something that makes you laugh because you haven’t seen it yet. Both of them had that. Adam was truly funny but in a style that was completely new and fresh.”

###

Friction at SNL

In 2019, Sandler returned to host SNL for the first time and centered his monologue on how much he loved being a cast member. Then he mentioned a question his daughter had asked. “If it was the greatest, Dad, then why did you leave?”

As the piano kicked in, Sandler began a ballad: “I was fired.”

Which is not exactly true. But Sandler’s SNL run, from 1990 to 1995, would see two factions emerge inside 30 Rockefeller Plaza. Those who got it and those who didn’t. Executives were known to lodge complaints about his work. And within the cliquey cast and writers room, there was also a split.

“At read-through, Adam would do an \[Weekend\] Update piece, like where he was a travel guide and the joke would be that he was just not doing what a travel guide is supposed to be doing,” says Robert Smigel, a writer on the show for eight years. “But he was delivering the information with a blissful idiot’s enthusiasm. And it was incredibly funny. And I just remember me and Conan \[O’Brien\] and the nerds — Greg Daniels and \[Bob\] Odenkirk — giggling uncontrollably in one corner of this room. This room that otherwise had a black cloud hanging over it.”

Jim Downey, the legendary writer who had worked with John Belushi, Gilda Radner and Bill Murray, decided early on that Sandler was the closest thing SNL ever had to Jerry Lewis. Those wacky voices, the off-kilter characters. He could also sing, bringing his acoustic guitar onto Weekend Update to do his irresistible tributes to Thanksgiving and Hanukkah (“O.J. Simpson, not a Jew. But guess who is? Hall of Famer Rod Carew — he converted.”) As Downey watched the split, between appreciators and disparagers**,** he developed a term to describe Sandler’s critics. *Half-brights*.

“Ordinary people had no problem with him, and really smart people had no problem,” says Downey. “But there was this group in the middle who would just take great offense at this kind of thing. They thought it was self-indulgent and infantile. And the thing about Adam was: … Most performers — it’s very important that they be respected as intelligent and often more intelligent than they really are. Adam was a guy who did not care if you thought he was smart and, in fact, went out of the way to obscure the fact that he is, I’d daresay, a lot more intelligent than 90 percent of the performers I’ve worked with.”

Sandler’s greatest bits were deceivingly multidimensional. “The Herlihy Boy,” named after his college roommate, was a commercial you would never see. A needy, potentially sociopathic man-child pleads to housesit (“Pleeeeeze … it would mean so much to me if you just let me water your plants”) or walk your grandmother across the street. Every minute or so, the camera pulls back to show Chris Farley as an exasperated older relative who wants you to give the damn kid a break while screaming, pleading and generally Farleying at full blast.

“To me, that was a rhythm piece,” says Sandler. “I’m going to calmly talk, Farley’s going to go f---ing bananas. Camera will zoom back in — calm energy — then widen to a sick man screaming. I knew that had a comedy rhythm to it. I learned that from SNL. I learned what made me laugh. Like [Dan Aykroyd on ‘Fred Garvin, Male Prostitute.’](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jphfMd4_LCs) That rhythm influenced me.”

Sandler’s most famous character may have been Canteen Boy, a voice and persona he would adapt for his hugely successful 1998 film, “The Waterboy,” and bring back nearly 25 years later for “Hubie Halloween.” Canteen Boy is a misfit — always dressed in Boy Scout attire with a baby-talk voice — who is universally mocked but still exudes a boastful pride.

“It wasn’t like a single joke that escalates,” says Smigel. “It was a conversation between a somewhat strange guy and a couple of other people who were perceived as normal. And the other guys are just kind of smirking and making ... comments that they think are going over his head, but they’re not. And the weird guy doesn’t want to let them know that they’re hurting him. So he’s acting like they’re going over his head, for his own dignity’s sake. So that’s a lot going on in a ‘Saturday Night Live’ sketch.”

Canteen Boy, like so many of his ideas, was polarizing. But it was, in a way, a microcosm of Sandler’s time on SNL — the smug, self-assured grown-ups looking down on the goofy kid who was much smarter than they realized.

“Somebody like Franken is like, ‘Really, Canteen Boy?’” says Smigel. “And I literally said to Al, ‘It’s the most complex sketch in read-through.’”

Franken wasn’t the only doubter. NBC’s executives complained, too. Don Ohlmeyer, a network president, targeted Sandler, Farley and Spade. *These guys aren’t funny,* he’d tell Michaels. *I think they are*, Michaels would respond. The execs longed for the past, for Roseanne Roseannadanna or Chevy’s pratfalls. They didn’t understand Sandler singing, “A turkey for me, a turkey for you, let’s eat turkey in a big brown shoe.”

“Whether it’s in painting or in music or in writing, style changes are disruptive,” says Michaels. “And the reaction to Adam on the show, in the world, was growing, but it wasn’t visible in the mainstream because they were all baby boomers.”

“I don’t think I ever met Don Ohlmeyer,” says Sandler. “I shook it off. That’s not what I heard when I walked down the street and some kid talked to me about [Crazy Pickle Arm](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lza3Q57t7YQ). I was going by the response of my New Hampshire friends calling me up, my father telling me his buddy’s kid thought such and such was funny. Or my brother. What he liked. I didn’t take it personally. I didn’t sit there and go, maybe I should change.”

By 1995, he had been at SNL for five seasons when Michaels talked with Sandler’s manager, Sandy Wernick. “Billy Madison” had come out a few months earlier. Wernick told Michaels that Sandler was filming “Happy Gilmore,” in which Sandler played a temperamental failed hockey player who joins the golf tour to save his grandmother from being evicted.

“I said, ‘Listen, I can protect him at the show, at least for now,’” says Michaels. “But they’re so adamant about his not being funny and not being good. So I think — go. He can leave.”

###

Winning audiences

Losing SNL was scary. “Billy Madison” had done well, but it wasn’t exactly “Ghostbusters.” He wondered whether he would keep getting opportunities.

“Maybe the other companies are going to start saying, ‘Don’t hire him because of this. They don’t like him over there. Maybe there’s a reason.’’’ Sandler says. “I was probably just nervous about that, but I didn’t doubt myself.”

By now, Sandler’s NYU team was humming. Herlihy would write with him. Giarraputo would help produce, do marketing, pitch in on jokes. Coraci came on board to direct “The Wedding Singer” and “Waterboy.” He would later do “Click,” “Blended” and “The Ridiculous 6.” Following Sandler’s lead, they focused on the audience, not the critics.

Test screenings would be key.

“Adam would sneak into the back of the theater and he would listen,” says Giarraputo. “As a comedian, it’s like a live audience — which jokes are working. Sometimes, we would have to open up spaces for jokes because they were laughing so hard.”

So when “Billy Madison” came out and was savaged by critics — Herlihy’s 84-year-old grandfather tried to comfort him after a Long Island Newsday writer compared the film to the horrors of Auschwitz — the gang jumped in a car and sneaked into theaters to watch audiences roar.

Ticket sales kept increasing. Home viewing on videotape, then DVD, was huge. “The Waterboy” made $186 million on a $23 million budget. “Big Daddy,” out in 1999, topped $230 million.

“Everybody wants to be loved,” says Tamra Davis, who directed “Billy Madison.” “But sometimes, it’s like when your parents don’t get your music. I kind of saw it as a badge of glory.”

###

Moving beyond comedy

In between his career-defining epics “Magnolia” and “There Will Be Blood,” Paul Thomas Anderson decided to write a movie for Sandler. Anderson loved watching a particular Sandler sketch on SNL, “[The Denise Show](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=twIgfEhXvXg),” where Sandler’s scorned ex-boyfriend, Brian, would throw a petulant, self-pitying tantrum. In 2002’s “Punch-Drunk Love,” he cast Sandler as pent-up lonely man Barry Egan opposite Emily Watson, and Sandler was the unexpected recipient of critical praise.

He then branched out into more romantic comedies, including “50 First Dates” with Drew Barrymore and “Just Go With It” with Jennifer Aniston.

That made perfect sense to Queen Latifah, who played his wife in last year’s “Hustle” and remembers laughing at him on SNL.

“I love ‘50 First Dates,’” she says. “Adam knows how to play the romantic comedy, and I think a lot of it is because this is a guy I would like to meet. This is a guy that would make me laugh. This is a guy who’s sweet. This is a guy who has real feelings and gets pissed off.”

Sandler’s dramatic side returned in Apatow’s “Funny People,” the 2009 film in which he played a darker, Rodney Dangerfield-ish version of a comic, and in 2017, when Noah Baumbach wrote a part for him as a musical and sweetly underappreciated house-dad opposite Dustin Hoffman’s narcissistic, insecure patriarch in “Meyerowitz.” Then came 2019’s “Uncut Gems,” a film by Josh and Benny Safdie. They had grown up with Sandler’s comedy albums from the 1990s. They spent years recruiting him to play the deeply flawed Howard Ratner, a jewelry dealer with a gambling addiction and a dissolving marriage.

“There’s this rage and this deep sweetness to him,” says Josh Safdie. “And he’s the only person who could have expressed what made Howard lovable for us.”

That range has also impressed his co-stars.

Jennifer Aniston, who has made three movies with Sandler, including the new Netflix adventure comedy “Murder Mystery 2,” remembers watching Sandler rhyme “deli” with “Arthur Fonzarelli” when he did “The Chanukah Song.”

“I mean, you couldn’t keep a straight face,” she says. “And personally, I think ‘\[You Don’t Mess With the\] Zohan’ is one of the funniest movies and then he has ‘Uncut Gems.’ It’s very rare for actors to be able to hit it out of the park in every genre.”

“I don’t know how he gets there. I have no idea,” says Eric Bogosian, who was [portrayed by Sandler on SNL](https://www.nbc.com/saturday-night-live/video/wfpas-monsters-of-monologue-94/2872689) in 1994, and who acted alongside him in “Uncut Gems” 25 years later. “But he does drop into a very centered place and speaks from a kind of authenticity when you watch his scenes.”

Sandler does not look for dramatic roles. He says his wife ultimately convinced him he was right for “Uncut Gems” after he expressed apprehension about the role.

“When I see him like that,” says Jackie in an email, “I let him know why I think he would be great at that specific part and why I think his fans would like to see him be that character. Because people coming up on the street and telling him how much one of his movies meant to them, that’s what drives him.”

Sandler can also take a different approach on a project he’s hired for as an actor than one under Happy Madison Productions. He focuses on his part, not punching up the script or talking through shots or casting. One thing he doesn’t take these roles on for is to show something to his critics.

“But I do think he’s trying to prove something to himself,” says Dustin Hoffman.

“Adam does compete — with himself,” writes Jackie. “He wants to come up with something new that he hasn’t done before.”

In “The Meyerowitz Stories,” Hoffman says, there were times when Sandler would seem unsure of his performance and the older actor would find himself reassuring him.

“What I think he does that is similar to what I try to do is that you think a lot about what you’re to do with this so-called character,” says Hoffman. “And then when you get there, forget it all. What sticks is what then comes out. He’s very alive in the moment and not preplanned.”

Sandler’s material may have changed, but his personality has not. His primary mission is to make you laugh. Whether onstage or in his office, he will talk about his excitement over a project — that “Hustle” is the first Happy Madison production that wasn’t a comedy — but there will never be any whining about not getting an Oscar nomination for “Uncut Gems” or “Meyerowitz.”

“He’s not looking for pats on the back,” says Spade, who remains a close friend. “He’s already won.”

When Sandler was a kid, he just wanted to make it like Rodney, Eddie or Aykroyd. And he did. Then he got to do the roles James Caan or Robert Duvall could pull off. And then he got married and suddenly he had a family. He’ll celebrate his 20th anniversary with Jackie this summer, and more than anyone else she’s the one who counsels, pushes, advises him on what to do. With what roles to take and with the girls and their birthday parties, bat mitzvahs and college tours. At 56, he is both the king of comedy and the dad with every intention of taking off 10 pounds.

Back onstage in Pittsburgh, “Farley” comes late in the gig, but it’s not the finale. Instead, Sandler tells the crowd he loves them and says the next one is for Jackie. And then he’s strumming a familiar tune, “Grow Old With You” from “The Wedding Singer,” only this time he’s not sporting a mullet and Billy Idol isn’t there to offer vocal and moral support. The verses have been changed to match his real life.

*… Now when I get chubby*

*We do the couples cleanse*

*You tell me I should have been nominated*

*For “Hustle” and “Uncut Gems”*

*I said, “I’ll stick with the Kids’ Choice Awards*

*As I grow old with you”*

They are cheering now, with their “Happy Gilmore” hockey jerseys, their memories of Opera Man and that Hanukkah song, and Sandler, from the stage, turns the final line in his song back to the crowd.

*Thanks for growing old — with me.*

The Mark Twain Prize for American Humor ceremony will air at 8 p.m. March 26 on CNN.

The other evening, I was over at my friends’ place and we were comparing notes on our seventh-graders. Like in New York City, seventh grade in Montreal marks the traditional start of solo commuting on public transit. My friends’ kid has had some [trouble adapting](https://www.thecut.com/2022/09/the-dread-of-watching-your-kid-start-school.html) to the logistics of getting around alone. For a while, a parent would ride the bus with him, but he wanted to be more independent. He switches buses on the way to school, and that was the tricky part that needed practicing.

So for a week of [morning commutes](https://www.thecut.com/2015/03/11-facts-about-your-soul-sucking-commute.html), his stepdad tailed the bus on his bike, pedaling the snowy Montreal streets to make sure his stepson got off where he was supposed to. One morning, the kid missed his stop, and my friend had to race the bus, ditch his bike at the next stop, and rush on to get him. But now he’s riding alone every morning, a seventh-grader making his way.

As my kids get older, I am learning how labor-intensive it is to teach them to be independent, and I’m beginning to think that we have the helicopter-parent/hands-off-parent binary all wrong. Maybe helicopter parenting is a form of neglect, one that might even be comparable in its harmfulness to the kind of neglect that forces kids to grow up by their own wits. The crisis of teen [mental health](https://www.thecut.com/2022/02/stress-toys-for-kids.html) in the wake of COVID can be explained in all sorts of ways, but a common denominator is that many teenagers feel that they have[no control over their lives](https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2022/10/why-are-kids-so-sad.html), which is distressing for any human. When you teach a kid to be safely independent, you give them some of that control. Denying a kid that opportunity is cruelty disguised as parental virtue – it’s beyond fucked up and dark, when you really think about it.

I also wonder if we misunderstand some of the motivations for helicopter parenting. We assume it’s an anxiety response, and I’m sure that explains a lot of it, but it’s also the path of least resistance. I’m not one to call people out for being lazy — in Montreal, we prefer to call it “*l’art de vivre*” — but I might have to make an exception here.

“Sometimes it’s harder to parent your kids to become independent than it is to helicopter — it can be exhausting, and it can be time-consuming,” said Dr. Gail Saltz, clinical associate professor of psychiatry at New York-Presbyterian Hospital and host of the[*How Can I Help?*](https://www.iheart.com/podcast/1119-how-can-i-help-with-dr-ga-76281118/)podcast from iHeartRadio. As counterintuitive as it may seem, letting kids make mistakes, and being there to support (and clean up after) them, can be more work than doing everything yourself. “Your kid will leave the house with their shoes on the wrong feet, and you’ll think,*The teacher’s going to see this; what will they think?*” said Dr. Saltz. But the teacher has seen it all, and the kid will realize their feet hurt and figure out that they need to switch their shoes. “Little kids need little tasks,” said Dr. Saltz — like putting on shoes, brushing their own teeth.

Many parents instinctively intervene in these simple tasks, but it sets a precedent that can be hard to break later on. It takes a long-term oceanic presence of mind to teach kids independence. It’s not a set of tasks but an entire orientation that has to be maintained over the course of years. Repetition, correction, being available to help if something goes wrong — this is what teaching kids independence requires of us.

“Parents who are very involved, wanting to know what their child is doing in the world — that is often considered part of helicopter parenting, but that isn’t necessarily a problem,” said Saltz. “Being involved is distinct from wanting to help a child make all of their decisions. The problem is ‘I will help you do all the things. I will get involved in your conflicts. I will not let you make any mistakes.’” According to Saltz, even parents of young children should avoid approaching parenting as a troubleshooting exercise. Children become accustomed to this degree of parental involvement. The more time parents spend clearing the path for their offspring, the harder it is for children to adapt to facing obstacles on their own.

For parents who can afford to throw money at their problems by[hiring nannies and Ubers to shuttle their kids all over town](https://www.curbed.com/2023/02/upper-east-side-parents-axiety-teens-crime-covid.html), being overprotective is probably as much about expediency as it is about actual worry. It’s more convenient to outsource and schedule than to take the time and mental space to help kids handle anything semi-autonomously. But by failing to take the time to teach our kids to navigate a neighborhood (or load a dishwasher, for that matter), we’re prioritizing our own convenience over the long-term benefits for our kids.

Helicopter parenting is also a way of protecting yourself from the judgment of other parents. In fact, its specter can loom even larger than actual threats to children’s safety. The off-piste vigilance of strangers can make an otherwise safe, ordinary situation spiral into conflict and defensiveness.

Fearful and overprotective strangers can even feel like a threat — especially to parents of color, whose kids are[more likely to be seen as “loitering”](https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0264275120312336?casa_token=6qz1J4Z9VjMAAAAA:PTBXjf2Ve5QiMoMdv-GBTzxJYSrVW_X4GnCyZBiNaYTaTVtXt-_gkcJuWPE1HtNien4qCGfmmSZz)when they’re out in the world. We’ve all read the nightmare stories of mothers having their children put into foster care because their poverty was mistaken for neglect. Many of us have had our own brushes with a stranger on a rampage of carefulness, and it’s enough to make you think twice about letting your kids be independent at a young age.

When my kids were 5 and 2, I was doing fieldwork for my master’s thesis on the weekends while working full time during the week. (Notice how I instinctively position myself as hardworking and overextended so you’ll think I’m a good person worthy of sympathy.) One Sunday in March, I had to conduct an interview at a Tim Hortons, and since my husband was working, I brought the kids. I left them in the car, listening to music they liked — I could see them through the window from where I sat conducting my interview. Wouldn’t you know it, another woman clocked them too. I saw her standing by my car reaching for her phone, and I knew right away It Was Happening. I excused myself from the interview to run outside. She was on the verge of calling the cops, she said, because someone could come grab the kids at any moment. (It’s amazing how abduction by strangers is such a persistent fear among so many parents, when 99 percent of abductors are known to the child they take.) We exchanged words — I instinctively, Canadianly apologized, which I have regretted ever since — and she left.

I’ve thought about that woman for years. She had two teenage daughters with her, who witnessed the whole exchange. No doubt, as they drove away she reiterated to them that she would never have been so negligent with them when they were young. She was demonstrating fitness to them, responsibility, moral fortitude. But nothing had actually happened — no one had been in danger, and no one was saved. Sometimes, I think that as the world becomes increasingly complex and overfull of information, confused people seek out opportunities to feel like they have some idea of what’s going on. The vulnerability of children, as a concept, is not confusing. And that’s how we have found ourselves in a situation where childrenare overpoliced by strangers in public and parents consider it their duty to protect their kids from obstacles real and imagined.

We really owe it to ourselves and to our kids not to let our style be cramped by the threat of overzealous idiots on the hunt for opportunities to create order in their world. My kids have always been a bit more on the loose than average, and I’ve long harbored a shameful worry: If anything ever happened to them while roaming the neighborhood alone, not only would it be horrible for our family, but it would prove the anxious side right — and I would hate to have to live that down.

It doesn’t take only energy and attention to teach your kids to navigate independence safely. It takes a certain willingness to accept that someone out there might think you’re a bad parent. Allowing imagined judgment to cloud our decision making is like letting an internet comments section make our choices for us. Helicopter parenting is the manifestation of overlapping anxieties about the hazards of the world and about the opinions of other people. It’s also a product of the narcissistic delusion that our children’s (inevitable, developmentally necessary) failures are our own.

This newsletter has never been about giving advice, and I’m not about to start now, but I do have one request to make of all you city-dwelling readers. Next time you see a kid you know walking down the street by themselves, don’t ask them where their parents are. Ask them where they’re headed.

- [Are New Dads OK?](https://www.thecut.com/2023/03/how-can-new-fathers-support-each-other.html)

- [Cup of Jo’s Joanna Goddard Opens Up About Her Divorce](https://www.thecut.com/2023/02/cup-of-jo-joanna-goddard-divorce-parenting-interview.html)

- [What If You Just Didn’t Clean That Up?](https://www.thecut.com/2023/02/embracing-mess-vs-cleanliness.html)

# How an FBI agent stained an NCAA basketball corruption probe

The FBI agents arrived in Las Vegas with $135,000 and a plan.

They took over a sprawling penthouse at the Cosmopolitan, filled the in-room safe with government cash and stocked the wet bar with alcohol. Hidden cameras — including one installed near a crystal-encrusted wall in the living room — recorded visitors.

In the heart of a city known for heists and hangovers, the four agents were running an undercover operation as part of their probe into college basketball corruption that investigators code-named Ballerz.

One of the agents was posing as a deep-pocketed businessman wanting to bribe coaches to persuade their players to retain a particular sports management company when they turned professional. He distributed more than $40,000 in cash to a procession of coaches invited to the penthouse. The sting concluded at a poolside cabana on a blistering afternoon in July 2017 with a final envelope of cash passed to one last coach.

After that transaction, the lead case agent, Scott Carpenter, joined the undercover operative and the two other agents in eating and drinking their way through the $1,500 food and beverage minimum to rent the cabana.

Carpenter had consumed nearly a fifth of vodka and at least six beers by the time he returned to the penthouse to shower and change clothes before a night out.

He grabbed $10,000 in undercover cash from the penthouse safe, then headed to a high-limit lounge at the casino next door. What happened next would ultimately stain the investigation like a cocktail spilled on a white tablecloth.

Reporter Nathan Fenno recounts a lesser known scandal behind the FBI investigation into college basketball corruption — one that involved the lead case agent finding himself on the wrong side of the law after a wild weekend in Vegas.

The investigation was hailed as a watershed moment in men’s college basketball. But in an extensive reassessment, The Times examined thousands of pages of court testimony, intercepted phone calls, text messages, emails and performance reviews. The records provide a detailed look inside the high-profile investigation, led by a veteran FBI agent whose conduct on a vodka-soaked day in Las Vegas landed him on the wrong side of the law.

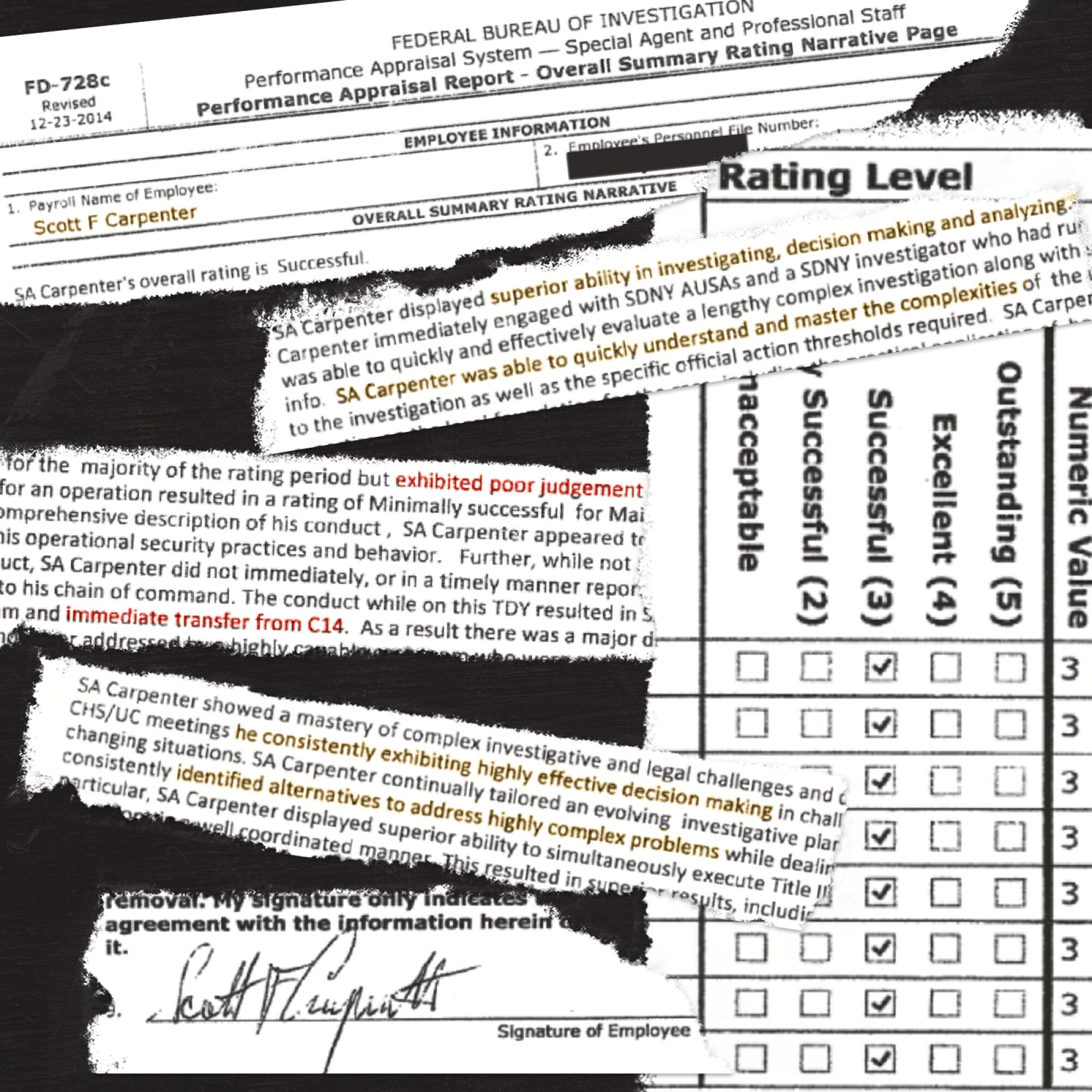

Ballerz was the top priority for the New York FBI’s public corruption squad for almost a year, according to Carpenter’s performance review in 2017, and included two undercover agents, operations in at least eight states, dozens of grand jury subpoenas and thousands of wiretapped phone calls.

The performance review and other court records offer new details about the lead case agent’s role and provide the most comprehensive account to date of the FBI’s handling of an investigation that, for all its hype, focused on lesser-known coaches and middlemen, most of them Black.

The weight of the federal government crashed down on college basketball at a livestreamed news conference in Manhattan when authorities unveiled the investigation in September 2017. The assistant director in charge of the New York FBI office warned potential cheaters that “we have your playbook.”

FBI agents, some with weapons drawn, had [arrested 10 men](https://www.latimes.com/94717652-132.html), including assistant coaches from USC, Arizona, Auburn and Oklahoma State. Prosecutors alleged that the coaches took bribes and, in a related scheme, that Adidas representatives funneled money to lure players to colleges the company sponsored.

Major universities and shoe companies were deluged with subpoenas. Coaches retained attorneys, even if they hadn’t been charged, and rumors swirled about the government’s next target in its crusade to clean up the sport.

Carpenter’s performance review said the “takedown has already had a major national impact and … is likely to continue to have major impact.” Prosecutors characterized the effort in a court filing as “arguably the biggest and most significant federal investigation and prosecution of corruption in college athletics.”

But almost six years later, the operation that was supposed to expose college basketball’s “dark underbelly” didn’t transform the sport. No head coaches or administrators were charged. There wasn’t a public outcry.

Instead, the meandering government effort seemed at times like an investigation searching for a crime, marshaling vast resources to ultimately round up an assortment of low-level figures for alleged wrongdoing — particularly the coach bribery scheme — that people involved in the sport said wasn’t a common practice until the FBI started handing out envelopes of cash.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

“This was a massive waste of time on everybody’s part,” said Jonathan Bradley Augustine, a former Florida youth basketball coach who was among those charged, though the charges were later dismissed. “It was a sexy case. This was big news. It was everywhere. … A lot of money wasted. A lot of people’s lives turned upside down.”

Scott Carpenter was the lead FBI agent on the undercover operation investigating corruption in men’s college basketball.

(Clay Rodery / For The Times)

> “He had started to become reliant on vodka. Whenever I saw him, he either had a drink or I could smell it on his breath. I didn’t connect this to bigger mental health issues or the symptoms of PTSD that I learned about later.”

— Frank Carpenter

The saga started more than a decade ago with a Pittsburgh financial advisor and two ill-fated movie projects.

Louis Martin Blazer III, whose clients included professional athletes, had pumped money into two minor films. “A Resurrection,” which was about a youngster who thinks his brother is returning from the dead, earned just $10,730 at the box office. The other movie, “Mafia,” went straight to DVD with the tagline: “He crossed the wrong cop.”

To bankroll the investments along with funding a music management company, the Securities and Exchange Commission later alleged, Blazer misappropriated $2.3 million from five clients between 2010 and 2012, forging documents, making “Ponzi-like payments” to hide the theft, faking a client’s signature and lying to investigators.

Seeking leniency, Blazer met with federal prosecutors and the SEC in New York in June 2014. He came clean about the fraud — and volunteered details about an unrelated scheme prosecutors didn’t know about in which he had paid about two dozen college athletes to use his financial services firm when they turned professional. This could have rendered the players ineligible under NCAA rules and left their schools vulnerable to sanctions.

That fall, prosecutors put Blazer to work as [a cooperating witness](https://www.latimes.com/sports/usc/story/2020-01-31/key-informant-cooperating-ncaas-probe-into-college-basketball-corruption) posing as a financial advisor trying to sign up college athletes as clients. He traveled the country to meet with agents, coaches, athletes and their family members, while recording conversations.

Blazer’s undercover operation had stalled by the time the FBI took over in November 2016, though the bureau saw “major unrealized potential” in the case, according to Carpenter’s performance review. Carpenter was transferred from the Eurasian organized crime squad to take over as the lead case agent on the basketball probe.

Scott Carpenter received a “successful” rating on his performance review and was mostly lauded for his work as the lead FBI agent on the investigation into college basketball corruption.

(Illustration by Los Angeles Times; Documents from court exhibits)

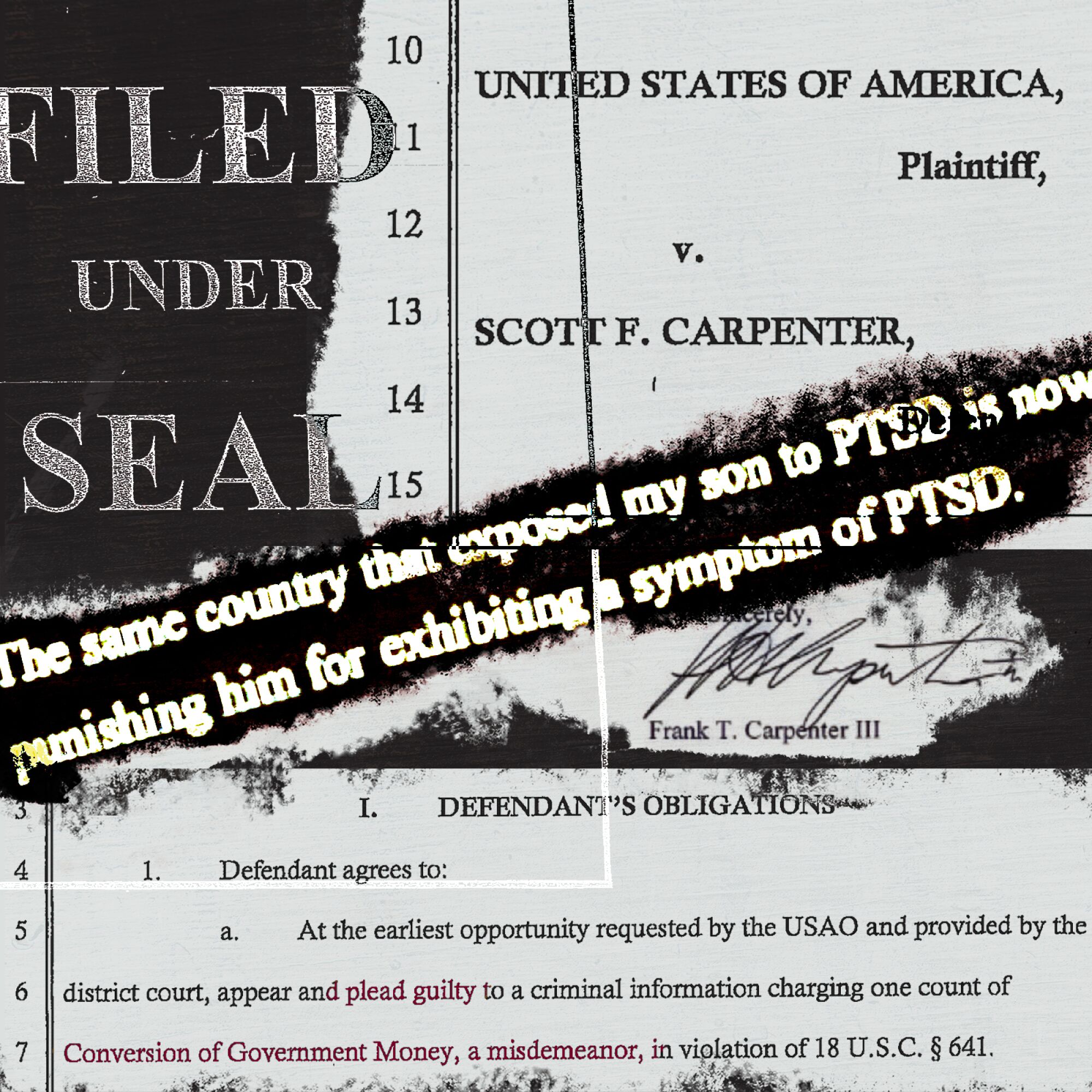

Raised in New Jersey as the son of a municipal judge and lawyer, Carpenter graduated from Wake Forest in the top of his ROTC class and served in Iraq as an officer with the 82nd Airborne. Carpenter’s annual officer evaluation in 2008 described his performance during 15 months in Baghdad as “absolutely phenomenal” with an “ability to turn chaos into order.” He left the Army that year as a captain, lived on the family’s sailboat and joined the FBI.

But signs of trouble began to emerge.

“He had started to become reliant on vodka,” his father, Frank Carpenter, would later write in a [letter filed in court](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/a9/50/97a3adc14dcaa700d2286618c3c6/42-carpenterfatherlettertocourt.pdf). “Whenever I saw him, he either had a drink or I could smell it on his breath. I still did not connect this to bigger mental health issues or the symptoms of PTSD that I learned about later.”

A court filing blamed his heavy drinking on the emotional toll from the lengthy deployment in Iraq and an improvised explosive device destroying the Humvee behind his vehicle.

At work, however, the complexities of the basketball probe appeared to be an ideal match for the skills of Scott Carpenter, who had worked on the high-profile investigation into global soccer corruption. His [performance review](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/bb/2e/eb59129c4c0083b75f31fd854e76/8-carpenterperformancereview.pdf) said Blazer had previously been “unsuccessful in developing evidence,” but became “highly productive” under Carpenter’s direction.

Without Carpenter, the performance review said, “it is likely there would have been minimal if any investigative results.”

Jeff D’Angelo had money and wanted to invest it in a sports management company. The exact source of his wealth wasn’t clear. Real estate? Restaurants? Family? Wherever it came from, he talked like someone who orchestrated major deals.

The thirty-something slicked back his hair, liked to mention he served in the military and had the thick biceps of a workout fiend.

One person who met D’Angelo described him as a “mix between a hedge fund baby and Jersey Shore Italian.”

In fact, “D’Angelo” was a pseudonym. He was an undercover FBI agent. Carpenter served as D’Angelo’s handler. The lead case agent’s performance review lauded the work, saying that the undercover agent “had the resources and guidance to significantly expand this investigation” thanks to Carpenter.

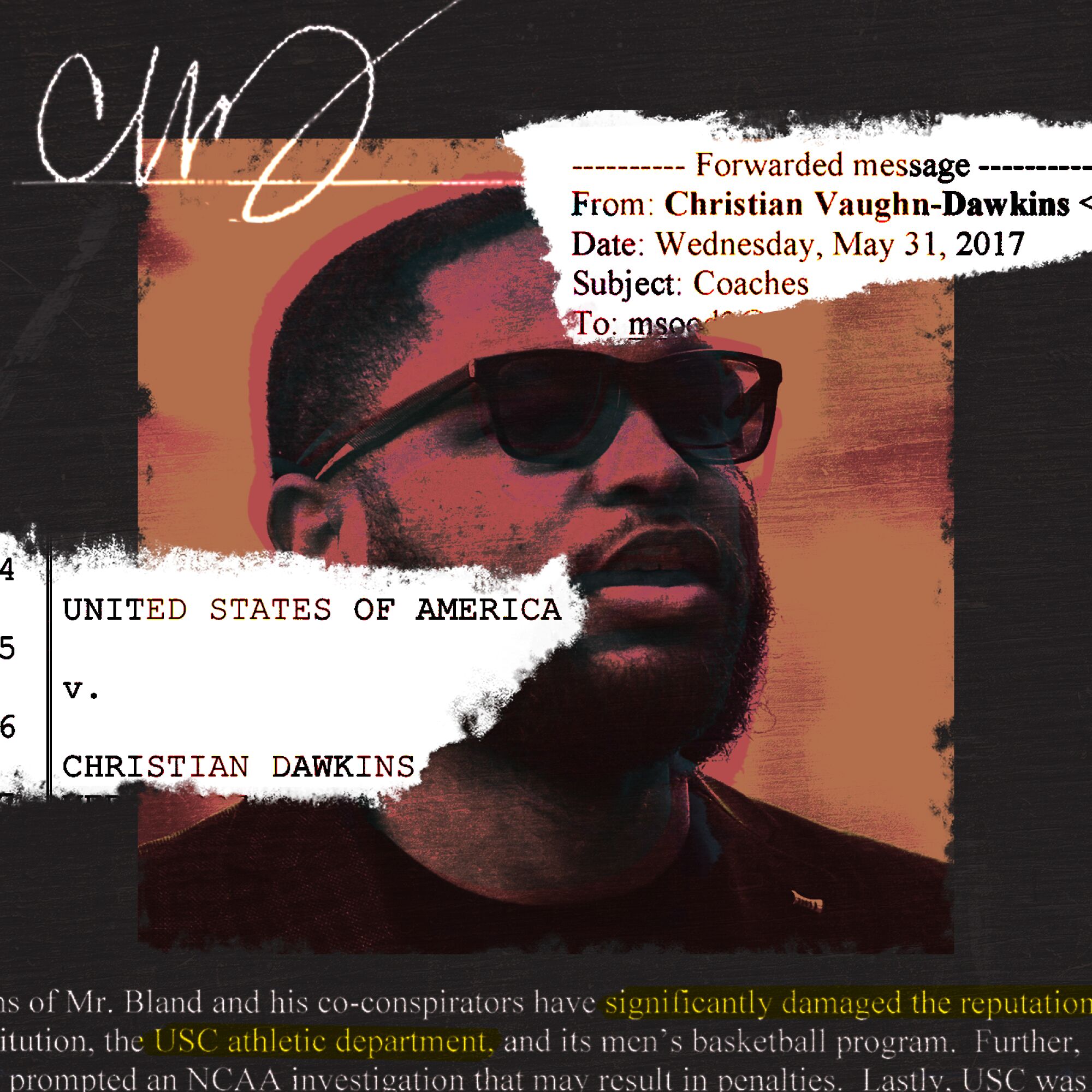

In mid-May 2017, D’Angelo was introduced at a Manhattan restaurant to Christian Dawkins, an ambitious 24-year-old attempting to start a sports management firm.

“If it makes sense ... I’ll invest,” D’Angelo said. “I would put down some capital.”

Christian Dawkins launched his sports management company with the help of a $185,000 loan from an investor called Jeff D’Angelo, who was really an undercover FBI agent.

(Clay Rodery / For The Times)

Dawkins had grown up in Saginaw, Mich., the son of a basketball coach and middle school principal, and hoped to become a sports agent or college coach. As a teenager, he started a high school basketball scouting service called “Best of the Best” and peddled it to college coaches for $600 a year. He was a relentless self-promoter, mentioning himself in prospect updates, adding inches to his true height and listing himself among “standout campers” at a clinic run by his father.

After the 2009 death of his younger brother Dorian from a heart ailment while playing basketball, Dawkins helped start a youth travel team named Dorian’s Pride. He created an event company called Living Out Your Dreams — LOYD for short — named himself chief executive and organized basketball camps.

Just shy of 21, Dawkins joined a Cleveland financial advisory firm working with NBA players. He later moved to New Jersey-based ASM Sports, recruiting clients for the powerhouse sports agency.

Dawkins continued to pursue the goal of leading his own sports management company. He connected with Blazer through a bespoke suit maker with deep links to professional basketball. Dawkins outlined his ambition in an email to Blazer and another associate in April 2016 that, like secret recordings of their meetings, ended up in the hands of authorities: “I want to have my own support system, and I want to be able to facilitate things on my own, independent of ASM. ... I just have to have the resources to continue.”

After the SEC accused Blazer of defrauding professional athletes in a news release the following month, Blazer testified that Dawkins “didn’t want to be around” him for almost a year.

In the meantime, Dawkins paid players and their families to retain ASM, according to his court testimony and exhibits, used two phones to stay in touch with some of the biggest names in the sport and relaxed in the green room at the NBA draft as players waited to be selected. When an associate joked in a text message that Dawkins seemed to be everywhere, he responded with apparent pride, “But never seen.”

On a windy afternoon in June 2017, Dawkins boarded a large yacht moored at the North Cove Marina in Manhattan’s Battery Park.

He expected to finalize the launch of his sports management company. In reality, the gathering was a setup. Everything was recorded. Among those in attendance were Blazer and D’Angelo, who introduced Dawkins to a wealthy friend named Jill Bailey. She was another undercover FBI agent.

In the [agreement signed](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/09/5a/526c75a646d0ac007890acfbda28/9-loydinccontract.pdf) that day, D’Angelo pledged to lend $185,000 to the company in exchange for a minority stake. Dawkins got 50% of the firm called Loyd Inc. and would be president. The company didn’t have a licensed NBA player agent, formal structure or even an office. D’Angelo — whose name was misspelled in the contract — handed out $25,000 in cash for the company’s start-up expenses.

In June 2017, Christian Dawkins, second from right with arms folded, boarded a two-story yacht in Manhattan expecting to finalize the launch of his sports management company. In reality, the gathering was a setup. (U.S. Justice Department)

D’Angelo wanted to pay college coaches to direct their players to use the new company when they became professionals, saying if the firm had “X amount of coaches that are on board with our business plan ... that’s just that many more kids we’re gonna have access to essentially every month.” Dawkins was skeptical. If the investor insisted on paying coaches, he argued, only “elite level dudes” should get money. Still, Dawkins offered to introduce D’Angelo to several coaches the following month when they flooded Las Vegas for a huge youth basketball tournament.

In the days and weeks that followed, Dawkins complained to associates in recorded conversations that bribing coaches was nonsensical. The best players usually spent less than a year on campus before leaving and had limited time with coaches. Parents, close relatives, youth coaches or middlemen, like Dawkins, exerted the real influence in the daily lives of many top-level players.

A system built around the NCAA’s ban on paying players and their families was lucrative for everyone but the people on the court. The NCAA brought in $761 million from the March Madness tournament in 2017. Multinational shoe companies paid universities to wear their gear. Top head coaches earned $4 million or more a year. It all helped to nurture a thriving underground economy with bidding wars for top players to attend universities, retain agents, sign with financial advisors.

The distribution of aboveboard money reflected only part of the power imbalance. While 81% of Division I athletic directors and 70% of men’s basketball head coaches were white in 2017, 56% of their players were Black. If the 47% of assistant coaches who were Black had a prayer of landing a head coaching job — or remaining employed — they needed to land top-level players.

The four college assistant coaches charged in Ballerz — and eight of the 10 initial defendants, including Dawkins — are Black. The four Black coaches all worked for white head coaches.

“When you’re a Black assistant coach, man, you’ve got the world on your shoulders,” said Merl Code, a former college basketball player who worked for Adidas and Nike and became a target of the sting. “If you don’t get kids, then you don’t keep your job. But if you don’t do what’s necessary to get kids, you’re not going to be successful, and what’s necessary to get the kids is to help the family.”

> “We’re just going to take these fools’ money.”

— Merl Code

In conversations with D’Angelo, who is white, Dawkins maintained that paying coaches to influence their athletes wasn’t “the end-all be-all.”

“I’m more powerful,” Dawkins told him, “than any coach you’re going to meet.”

The dispute came to a head during another recorded phone call a few weeks after the yacht meeting.

“If you just want to be Santa Claus and just give people money, well f—, let’s just take that money and just go to the strip club and just buy hookers,” Dawkins told D’Angelo. “But just to pay guys just for the sake of paying a guy just because he’s at a school, that doesn’t make common sense to me.”

D’Angelo wasn’t swayed. The investigation was built around ensnaring coaches.

“Here, here, here, here’s the model,” D’Angelo stammered.

He had the money, he said. They would pay coaches.

“I respect that ... you don’t think that’s the best approach, but that’s what I’m doing,” D’Angelo said in the call. “That’s just what it’s going to be.”

Afterward, Dawkins vented to Code in a wiretapped phone call that throwing cash at a slew of coaches meant spending lots of money for no discernible purpose.

“We’re just going to take these fools’ money,” Code said.

“Exactly,” Dawkins replied. “Because it doesn’t make sense. ... I’ve tried to explain to them multiple f— times. This is not the way you wanna go.”

Christian Dawkins set up a sports management company and boasted to potential investors of his relationships with prominent college basketball coaches. In reality, the biggest investor in his firm was an undercover FBI agent.

(Illustration by Los Angeles Times; Photo by Seth Wenig / Associated Press; Documents from court exhibits)

During a call with an associate in early July, Dawkins wondered aloud if he should find someone to pay back the money D’Angelo had invested in Loyd and end their relationship. The investor’s odd requests, like wanting to meet players and their parents, unnerved Dawkins. He wondered why D’Angelo cared so much.

“People are gonna think that honestly they’re being set up,” Dawkins said in the recorded call.

But he still wanted D’Angelo’s cash. A few days after the call, Dawkins and Code faced a problem. Prosecutors alleged they had agreed to help funnel cash from an Adidas company employee to the family of a touted high school prospect who had agreed to play for an Adidas-sponsored university. An installment had been delayed. D’Angelo agreed to provide a loan of $25,000.

The payment came at a critical point in the investigation, according to Carpenter’s [performance review](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/bb/2e/eb59129c4c0083b75f31fd854e76/8-carpenterperformancereview.pdf). He pushed for it to preserve D’Angelo’s “bona fides as a high roller” and “set in motion events which would widely expand the case from addressing bribery by NCAA coaches to incorporating the illegal conduct of officials at a major international sportswear company.”

As the Las Vegas trip approached, Code and Dawkins brainstormed which coaches could meet D’Angelo, but Code’s unease about the investor was growing.

“I’m looking up Jeff D’Angelo and I can’t find nothing on him,” Code told Dawkins in a phone call on July 24, 2017, “and that s— is really concerning to me.”

Carpenter flew to Las Vegas on July 27, 2017, accompanied by a supervisor, junior agent and the undercover operative — and having “serious misgivings” about whether he had enough personnel to run the operation.

Over three days, D’Angelo, Dawkins and Blazer met with 11 coaches — 10 college assistants and one youth coach, all in town for the youth tournament — at the Cosmopolitan. The trendy hotel that advertised “Just the right amount of wrong” seemed to be the ideal setting.

Tony Bland, in a white shirt, was among the college coaches who met with Jeff D’Angelo and Christian Dawkins in the penthouse suite at the Cosmopolitan. (U.S. Justice Department)

Augustine, the Florida youth coach, recalled that Blazer fixed him a vodka water when he stopped by the penthouse on the first night. The opulent surroundings staggered the coach. His players were jammed into rooms at a budget-friendly hotel. The penthouse appeared to be a different world. Black marble and dark wood. Enough seating — bar stools, couches, easy chairs — for a full team. Master bathrooms that rivaled the size of some hotel rooms. A huge balcony. Quirky art around every corner, like the enormous photo of a golden-hued woman dancing underwater in a swirl of purple fabric.

Augustine received an envelope from D’Angelo stuffed with $12,700, according to the complaint. The next day, Augustine said he deposited much of the cash at a nearby bank and, since his players had flown to Las Vegas on one-way tickets, used some of the windfall to pay their way home. Augustine said he used the remainder to pay down debt he had accumulated while running the team. (He was later charged with four felonies, but all counts were dropped.)

The hidden agendas at play in the penthouse seemed tailor-made for Sin City. D’Angelo distributed envelopes of bribe money as cameras recorded each transaction. But Dawkins later claimed he had arranged for three of the coaches to give him their would-be bribe money so he could run the company his way.

Dawkins pleaded with Preston Murphy, then a Creighton University assistant coach and longtime family friend, to meet with D’Angelo in the penthouse, saying he would be forced to move in with his parents if the financial backers didn’t support him, according to Murphy’s attorney.

“I needed him to basically help me, you know, continue to get funding,” Dawkins testified.

Former Creighton assistant coach Preston Murphy, left, was caught up in the investigation but was never charged. Former USC assistant coach Tony Bland, right, pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit bribery and was sentenced to probation for admitting to receiving $4,100.

(Associated Press)

NCAA investigators said in reports that Murphy and TCU assistant coach Corey Barker knew before their meetings in the penthouse on July 28 that they would be paid and had agreed to give all of the money to Dawkins. Prosecutors alleged Murphy and Barker each received $6,000 from D’Angelo. Murphy handed the cash over to Dawkins in a bathroom off the main casino floor, while Barker did the same near the hotel’s valet parking stand, according to accounts they gave to the NCAA. The same day, Dawkins deposited $5,000 in cash into the Loyd bank account. (Neither Barker nor Murphy was charged.)

Shortly after midnight on July 29, Tony Bland, a USC assistant coach, sank into a couch in the penthouse. He had arrived from L.A. that afternoon and looked tired. The conversation sounded like the others — boasts about influence over college players, banter about prospects with a shot at the NBA.

“I have some guys that I bring in that I can just say, this is what you’re f— doing,” Bland said. “And there’s other guys who we’ll have to work a little harder for, but we’ll still have a heavy influence on what they do.”

Hidden-camera footage shows Dawkins, not Bland, pick up an envelope of cash from the coffee table. The federal criminal complaint alleged Bland — making more than $300,000 a year at USC — got the $13,000 in the envelope. But bank records show Dawkins deposited $8,900 at an ATM later that day. Bland eventually pleaded guilty to receiving $4,100, the difference between the $13,000 and the deposit.

Dawkins testified that the actual amount Bland received was less because he only gave Bland “between $1,000 and $2,000” to spend at a bachelor party that night.

For the final undercover meeting, the FBI team had rented a poolside cabana at the Cosmopolitan. Afterwards, the agents decided to use the cabana for themselves when they learned the $1,500 they paid for the space was actually a food and beverage minimum, according to a [court filing](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/c7/8f/40d69cf541069242c47743d52cbb/carpenterpresentencingmemo.pdf).

“Despite the obstacles, all of the undercover meetings were very successful,” Carpenter’s attorney wrote in a court filing. “At the same time, there is no doubt that the intensity, anxiety, elation and exhaustion of the weekend’s activities left Mr. Carpenter in an even more precarious position.”

After showering and changing clothes in the penthouse following the alcohol-filled afternoon at the cabana, the four FBI agents walked next door to the Bellagio Hotel and Casino and ended up at a high-limit lounge.

Carpenter bought $10,000 in gambling chips with the government cash he had taken from the penthouse safe and started playing blackjack. The three other agents — including Carpenter’s supervisor — watched him gamble from an adjacent bar and took turns visiting, according to court testimony and a [filing by his attorney](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/c7/8f/40d69cf541069242c47743d52cbb/carpenterpresentencingmemo.pdf), as Carpenter gulped free drinks and lost.

“They at least had to have a decent idea it was undercover FBI money and nobody took the keys to the car,” Carpenter’s attorney Paul Fishman said in court.

The lead FBI agent lost $13,500 in government cash while gambling in Las Vegas.

(Clay Rodery / For The Times)

Carpenter churned through the $10,000, then pressed the undercover agent — D’Angelo — for additional government cash. He handed it over.

According to [a court filing](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/c9/31/94688de447b5a30af7a49286f87a/gov-uscourts-nvd-154467-3-0-1.pdf), Carpenter played for two to three hours, placed an average bet of $721 and, by the time he walked away, had lost $13,500.

As the alcohol wore off in the early hours of July 30, Carpenter paced around the penthouse. According to a document [read in court](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/7e/9c/c2e40c004f1dbe86c8bab5080dc7/carpentersentencingtranscript.pdf), one of the agents told an investigator that Carpenter was brainstorming how to make it right and asked if they could say the gambling was part of the operation. The agent refused.

The undercover agent alleged that the four agents met early that morning and “there was a discussion ... to just take care of it,” Assistant U.S. Atty. Daniel Schiess said in court. The supervisor and junior agent, Schiess said, “hotly contest” that such a meeting occurred.

In a court filing, Carpenter’s attorney wrote that his client “vehemently disagrees” that he “intended in any way to conceal his conduct or evade responsibility.”

After returning to New York and taking a scheduled day off, Schiess said, Carpenter met with his supervisor about the missing money and, afterward, told the undercover agent and the junior agent he was going to try to pay it back and asked if they could split the cost. The other agents and Carpenter’s supervisor who was in Las Vegas aren’t identified in court records.

> “Carpenter appeared to have displayed poor judgment in some of his operational security practices and behavior ...”

— FBI performance review