"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/How ‘The Bear’ Captures the Panic of Modern Work.md\"> How ‘The Bear’ Captures the Panic of Modern Work </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/After the Zodiac Killer's '340' Cipher Stumped the FBI, Three Amateurs Made a Breakthrough.md\"> After the Zodiac Killer's '340' Cipher Stumped the FBI, Three Amateurs Made a Breakthrough </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/YouTube Fraud Led to $23 Million in Royalties for 2 Men, IRS Says.md\"> YouTube Fraud Led to $23 Million in Royalties for 2 Men, IRS Says </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Donald Trump and American Intelligence’s Years of Conflict.md\"> Donald Trump and American Intelligence’s Years of Conflict </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/How Bolivia’s ruthless tin baron saved thousands of Jewish refugees.md\"> How Bolivia’s ruthless tin baron saved thousands of Jewish refugees </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Unlikely Rise of Slim Pickins, the First Black-Owned Outdoors Retailer in the Country.md\"> The Unlikely Rise of Slim Pickins, the First Black-Owned Outdoors Retailer in the Country </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Twitter is becoming a lost city.md\"> Twitter is becoming a lost city </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Then Again Dying man’s note nearly turned history upside down - VTDigger.md\"> Then Again Dying man’s note nearly turned history upside down - VTDigger </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The metamorphosis of J.K. Rowling.md\"> The metamorphosis of J.K. Rowling </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Scenes from an Open Marriage - The Paris Review.md\"> Scenes from an Open Marriage - The Paris Review </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Saudi Crown Prince’s $500 Billion ’Smart City’ Faces Major Setbacks.md\"> Saudi Crown Prince’s $500 Billion ’Smart City’ Faces Major Setbacks </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Hollywood's Finest series on pregnancy and homelessness - Los Angeles Times.md\"> Hollywood's Finest series on pregnancy and homelessness - Los Angeles Times </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/It was a secret road map for breaking the law to get an abortion. Now, ‘The List’ and its tactics are resurfacing.md\"> It was a secret road map for breaking the law to get an abortion. Now, ‘The List’ and its tactics are resurfacing </a>"

],

],

"Renamed":[

"Renamed":[

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How ‘The Bear’ Captures the Panic of Modern Work.md\"> How ‘The Bear’ Captures the Panic of Modern Work </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/After the Zodiac Killer's '340' Cipher Stumped the FBI, Three Amateurs Made a Breakthrough.md\"> After the Zodiac Killer's '340' Cipher Stumped the FBI, Three Amateurs Made a Breakthrough </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/YouTube Fraud Led to $23 Million in Royalties for 2 Men, IRS Says.md\"> YouTube Fraud Led to $23 Million in Royalties for 2 Men, IRS Says </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Donald Trump and American Intelligence’s Years of Conflict.md\"> Donald Trump and American Intelligence’s Years of Conflict </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How Bolivia’s ruthless tin baron saved thousands of Jewish refugees.md\"> How Bolivia’s ruthless tin baron saved thousands of Jewish refugees </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Unlikely Rise of Slim Pickins, the First Black-Owned Outdoors Retailer in the Country.md\"> The Unlikely Rise of Slim Pickins, the First Black-Owned Outdoors Retailer in the Country </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Twitter is becoming a lost city.md\"> Twitter is becoming a lost city </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Then Again Dying man’s note nearly turned history upside down - VTDigger.md\"> Then Again Dying man’s note nearly turned history upside down - VTDigger </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.01 Admin/Calendars/2022-08-10 Meg's mum back to Belfast.md\"> 2022-08-10 Meg's mum back to Belfast </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.01 Admin/Calendars/2022-08-10 Meg's mum back to Belfast.md\"> 2022-08-10 Meg's mum back to Belfast </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Why Putting Solar Canopies on Parking Lots Is a Smart Green Move.md\"> Why Putting Solar Canopies on Parking Lots Is a Smart Green Move </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Why Putting Solar Canopies on Parking Lots Is a Smart Green Move.md\"> Why Putting Solar Canopies on Parking Lots Is a Smart Green Move </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Biggest Change in Media Since Cable Is Happening Right Now.md\"> The Biggest Change in Media Since Cable Is Happening Right Now </a>"

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How ‘The Bear’ Captures the Panic of Modern Work.md\"> How ‘The Bear’ Captures the Panic of Modern Work </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/YouTube Fraud Led to $23 Million in Royalties for 2 Men, IRS Says.md\"> YouTube Fraud Led to $23 Million in Royalties for 2 Men, IRS Says </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/After the Zodiac Killer's '340' Cipher Stumped the FBI, Three Amateurs Made a Breakthrough.md\"> After the Zodiac Killer's '340' Cipher Stumped the FBI, Three Amateurs Made a Breakthrough </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How Bolivia’s ruthless tin baron saved thousands of Jewish refugees.md\"> How Bolivia’s ruthless tin baron saved thousands of Jewish refugees </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Donald Trump and American Intelligence’s Years of Conflict.md\"> Donald Trump and American Intelligence’s Years of Conflict </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Unlikely Rise of Slim Pickins, the First Black-Owned Outdoors Retailer in the Country.md\"> The Unlikely Rise of Slim Pickins, the First Black-Owned Outdoors Retailer in the Country </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Then Again Dying man’s note nearly turned history upside down - VTDigger.md\"> Then Again Dying man’s note nearly turned history upside down - VTDigger </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Twitter is becoming a lost city.md\"> Twitter is becoming a lost city </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Why Putting Solar Canopies on Parking Lots Is a Smart Green Move.md\"> Why Putting Solar Canopies on Parking Lots Is a Smart Green Move </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Why Putting Solar Canopies on Parking Lots Is a Smart Green Move.md\"> Why Putting Solar Canopies on Parking Lots Is a Smart Green Move </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Why Putting Solar Canopies on Parking Lots Is a Smart Green Move.md\"> Why Putting Solar Canopies on Parking Lots Is a Smart Green Move </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/Why Putting Solar Canopies on Parking Lots Is a Smart Green Move.md\"> Why Putting Solar Canopies on Parking Lots Is a Smart Green Move </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/While Britain burns, the Tories are … fiddling with themselves again Marina Hyde.md\"> While Britain burns, the Tories are … fiddling with themselves again Marina Hyde </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/While Britain burns, the Tories are … fiddling with themselves again Marina Hyde.md\"> While Britain burns, the Tories are … fiddling with themselves again Marina Hyde </a>",

@ -5034,27 +5104,7 @@

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/La promesse de l'aube.md\"> La promesse de l'aube </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/La promesse de l'aube.md\"> La promesse de l'aube </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/At 88, Poker Legend Doyle Brunson Is Still Bluffing. Or Is He.md\"> At 88, Poker Legend Doyle Brunson Is Still Bluffing. Or Is He </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Jeff Bezos’s Next Monopoly The Press.md\"> Jeff Bezos’s Next Monopoly The Press </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Biggest Change in Media Since Cable Is Happening Right Now.md\"> The Biggest Change in Media Since Cable Is Happening Right Now </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/As El Salvador’s president tries to silence free press, journalist brothers expose his ties to street gangs - Los Angeles Times.md\"> As El Salvador’s president tries to silence free press, journalist brothers expose his ties to street gangs - Los Angeles Times </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Two Professors Found What Creates a Mass Shooter. Will Politicians Pay Attention.md\"> Two Professors Found What Creates a Mass Shooter. Will Politicians Pay Attention </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/What did the ancient Maya see in the stars Their descendants team up with scientists to find out.md\"> What did the ancient Maya see in the stars Their descendants team up with scientists to find out </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Hazing, fighting, sexual assaults How Valley Forge Military Academy devolved into “Lord of the Flies”.md\"> Hazing, fighting, sexual assaults How Valley Forge Military Academy devolved into “Lord of the Flies” </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Dianne Feinstein, the Institutionalist.md\"> Dianne Feinstein, the Institutionalist </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/The Follower.md\"> The Follower </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Deshaun Watson’s Massages Were Enabled by the Texans and a Spa Owner.md\"> Deshaun Watson’s Massages Were Enabled by the Texans and a Spa Owner </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Waiting for keys, unable to break down doors Uvalde schools police chief defends delay in confronting gunman.md\"> Waiting for keys, unable to break down doors Uvalde schools police chief defends delay in confronting gunman </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Albert Camus The philosopher who resisted despair.md\"> Albert Camus The philosopher who resisted despair </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/He was my high school journalism teacher. Then I investigated his relationships with teenage girls..md\"> He was my high school journalism teacher. Then I investigated his relationships with teenage girls. </a>"

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/How ‘The Bear’ Captures the Panic of Modern Work.md\"> How ‘The Bear’ Captures the Panic of Modern Work </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/After the Zodiac Killer's '340' Cipher Stumped the FBI, Three Amateurs Made a Breakthrough.md\"> After the Zodiac Killer's '340' Cipher Stumped the FBI, Three Amateurs Made a Breakthrough </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Then Again Dying man’s note nearly turned history upside down - VTDigger.md\"> Then Again Dying man’s note nearly turned history upside down - VTDigger </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Twitter is becoming a lost city.md\"> Twitter is becoming a lost city </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/After the Zodiac Killer's '340' Cipher Stumped the FBI, Three Amateurs Made a Breakthrough.md\"> After the Zodiac Killer's '340' Cipher Stumped the FBI, Three Amateurs Made a Breakthrough </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/YouTube Fraud Led to $23 Million in Royalties for 2 Men, IRS Says.md\"> YouTube Fraud Led to $23 Million in Royalties for 2 Men, IRS Says </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Donald Trump and American Intelligence’s Years of Conflict.md\"> Donald Trump and American Intelligence’s Years of Conflict </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/How Bolivia’s ruthless tin baron saved thousands of Jewish refugees.md\"> How Bolivia’s ruthless tin baron saved thousands of Jewish refugees </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.02 Inbox/The Unlikely Rise of Slim Pickins, the First Black-Owned Outdoors Retailer in the Country.md\"> The Unlikely Rise of Slim Pickins, the First Black-Owned Outdoors Retailer in the Country </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Then Again Dying man’s note nearly turned history upside down - VTDigger.md\"> Then Again Dying man’s note nearly turned history upside down - VTDigger </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/Twitter is becoming a lost city.md\"> Twitter is becoming a lost city </a>",

"<a class=\"internal-link\" href=\"00.03 News/How PM’s former aide had to ‘nanny him’ through lockdown.md\"> How PM’s former aide had to ‘nanny him’ through lockdown </a>",

- [x] 11:34 [[Selfhosting]], [[Configuring Fail2ban|Fail2ban]], [[Configuring UFW|UFW]]: voir si la liste d'IP peut etre partagee avec [crowdsec](https://crowdsec.net) 📅 2022-04-30 ✅ 2022-04-16

- [x] 11:34 :desktop_computer: [[Selfhosting]], [[Configuring Fail2ban|Fail2ban]], [[Configuring UFW|UFW]]: voir si la liste d'IP peut etre partagee avec [crowdsec](https://crowdsec.net) 📅 2022-04-30 ✅ 2022-04-16 ^tb7swm

- [x] 15:39 [[Selfhosting]], [[Configuring Caddy|caddy]]: Mettre en place le monitoring par Prometheus 📅 2022-04-03 ✅ 2022-04-02

- [x] 15:39 :desktop_computer: [[Selfhosting]], [[Configuring Caddy|caddy]]: Mettre en place le monitoring par Prometheus 📅 2022-04-03 ✅ 2022-04-02 ^mxs2dm

# After the Zodiac Killer's '340' Cipher Stumped the FBI, Three Amateurs Made a Breakthrough

**The envelope arrived** at the *San Francisco Chronicle* in November 1969 without a return address, its directive to the recipient, in handwriting distinctively slanted and words unevenly spaced, to “please rush to editor.” The *Chronicle* newsroom had seen the scrawl before, on previous letters sent from the Zodiac, a self-monikered serial killer who threatened to go on a “kill rampage” if the paper didn’t publish his writing on its front page. By the time of the November letter, the Zodiac had already attacked seven people, murdering five. His most recent murder—of a San Francisco cab driver, by gunshot—had occurred just four weeks before this new envelope arrived. The Zodiac had mailed the *Chronicle* a piece of the victim’s bloodied shirt as evidence of the crime.

The Zodiac’s letters were replete with grisly imagery. He signed his “name” with a crosshairs symbol. He shared haunting details of his attacks. He promised to blow up buses of schoolchildren and unleash a “death machine” on San Francisco. But in addition to these overt threats, he included baffling ciphers for investigators to crack, troubling grids of symbols and letters that presumably masked a secret about his identity, intentions, or victims (to this day, the killer has never been found). The Zodiac’s first cipher, included in the July 31 letter, had been solved within a week by an amateur husband-and-wife team—but it had only revealed more of the killer’s raving. The second, now known as “the 340” due to the number of characters in it, would prove a much more difficult challenge. It came with a letter for the *Chronicle*, reading in part:

*PS could you print this new cipher in your frunt page? I get aufully lonely when I am ignored, so lonely I could do my Thing !!!!!!*

The paper’s editors, along with local law enforcement officials, had no reason to doubt the Zodiac’s most recent threat. They published the 340 the next day, hoping it might bring them one step closer to the serial killer’s identity, or lead them to his next victims.

But the 340 stumped both amateur and professional cryptographers alike—not just in the weeks following its publication, but for decades. The NSA couldn’t crack it. Neither could the Naval Intelligence Office or the FBI. For more than fifty years, the cipher remained an unsolvable enigma, one that grew to almost mythic proportions among codebreakers and cryptography sleuths. Some speculated that the cipher would never be solved—that it was too sophisticated, too challenging for even contemporary cryptographers.

The 340 cipher, above, reached the *San Francisco Chronicle* in November 1969. The killer’s first cipher had been cracked in a week by an amateur husband-and-wife team. Solving this one would require the eventual codebreakers to employ homophonic substitutions, period-19 transposition, the knight’s tour, and other complex cryptology schemes.

Getty Images

But then, in December 2020, the FBI announced a breakthrough: The 340 cipher had been solved. Not by its crack Cryptanalysis and Racketeering Records Unit, but instead by three computer wonks who’d found one another on an obscure online true-crime discussion board and started collaborating during the COVID-19 pandemic. The trio, who had no background in cryptology and no professional codebreaking experience, did what the world’s most powerful intelligence organizations could not. On top of the solution’s haunting opacity, the intricacies of the cipher itself brought fresh layers of insight that, forensic experts say, might help authorities eventually, finally, catch up to the killer.

> “There’s not a lot of rhyme or reason to it, which makes it very impressive that anyone solved it.”

**Dave Oranchak has** always been a puzzle geek. When he’s not running ultramarathons near his home in Roanoke, Virginia, the 47-year-old computer programmer spends most of his time working out practical solutions to problems, whether in his coding work or his passion for Shinro, a Japanese derivation of Sudoku. Around 2006, Oranchak became intrigued by the 340’s apparent resistance to a solution, a key had eluded the best efforts of professionals and experts. Tempted by the chance to unlock a slate of notorious cold cases, he started nosing around online discussion boards about the Zodiac. Before he knew it, he was down the rabbit hole, immersed in the Zodiac’s story and gaining a reputation as one of the reigning experts on the killer’s ciphers.

The Zodiac had a thick case file for amateur sleuths like Oranchak to peruse. Here was a serial killer who had gone out of his way to taunt the police. His handwriting was on file, along with a recording of his voice. Witnesses to his crimes had provided enough information for law enforcement to create a composite sketch of his face. The Zodiac had tallied his victims in marker on the side of a car, drafted homemade ciphers, and mailed scraps of evidence to newspapers. But despite the best efforts of the country’s leading intelligence agencies, no one knew who he was. The 340 cipher was one of the final threads to pull, a puzzle with seemingly no discernible rules, schemes, or internal logic.

Oranchak dedicated hundreds of hours to the 340 cipher—“way too many,” by his own measure. As his commitment deepened, he became a respected moderator on the Zodiac discussion boards and the leading authority on the 340 itself. He appeared on TV documentaries and podcasts dedicated to the Zodiac, eventually giving talks at NSA-sponsored cryptology conferences and sitting on panels with FBI agents actively working in the cryptology field.

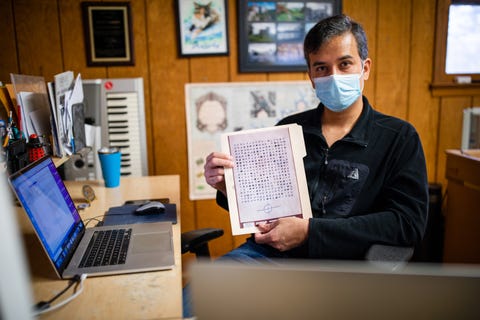

One of the three amateurs who broke the 340 code, David Oranchak did most of his work from his home office, his dog Rosa by his side while he sat at his computer. He detailed his thought processes and methods on his YouTube channel, where he connected with others attempting to crack the cipher.

PETER MEANS/VTE

The community of amateur Zodiac hunters can be sensationalistic. “There’s a lot of chatter and nonsense and arguing about suspects,” Oranchak says. But one member of the forums struck him as level-headed and critical: Jarl Van Eycke, a reclusive warehouse worker living in Belgium who had gained respect in the cryptology community after developing his own decryption software program. “Jarl was technically minded, and \[he was\] approaching the \[Zodiac\] problem rationally,” Oranchak says.

Van Eycke declined an interview request for this story. And he’s never spoken on the record about his decryption software or the Zodiac case. Oranchak has never met him; they’ve corresponded only by email and on forums. Despite Van Eycke’s almost total obscurity, he agreed to work with Oranchak on a solution to the 340. That was a pivotal moment that would add speed to the codebreaking process; Van Eycke’s software could work through multiple solution sequences simultaneously and provide a rating for the correctness of each result.

Van Eycke and Oranchak began programming the codebreaking software to work through thousands and thousands of possible solutions to the 340 cipher. During the pandemic, Oranchak launched a YouTube channel dedicated to their work from his home office; his family vacation photos and a watercolor portrait of the late family cat, Peabody, looked on as he issued heady primers about cryptology and codebreaking.

Despite the homespun setting, the information in Oranchak’s videos was undeniably sophisticated. He used Scrabble tiles to explain substitution keys and anagrams and gave casual lectures on cipher organization strategies such as columnar transposition, in which messages are first written in columns rather than lines. Before long, videos on his channel had millions of views. Oranchak was sure that certain anomalies in the cipher pointed to a logical organizational strategy. While some dismissed the cipher as an impossible exercise from a deranged mind, Oranchak believed that a valuable solution lay behind the inscrutable symbols.

**Oranchak’s belief in** the 340’s logic stemmed from cryptography’s foundational principles. Ciphers date back at least 3,000 years. The earliest known cryptogram is from 1500 B.C., when a Mesopotamian potter devised a code to keep his glaze recipe secret from competitors, but methodologies have diversified and proliferated since then. Ancient Spartans and Chinese military leaders used the “scytale” method, writing messages that could only be read when wrapped around a specific rod, and Julius Caesar popularized the substitution cipher, in which each letter is replaced by another letter that’s a set number of positions away in the alphabet. Sir Francis Bacon favored a “steganographic” approach in which he replaced letters with binaries, and during each of the World Wars, countries used a range of cryptography methods, from simple stencils to the legendary German Enigma machine. All of these cipher varieties employ rotating substitutions that can be “brute forced” by nothing but pencil and paper, says Riad Wahby, Ph.D., whose research at Carnegie Mellon University focuses on proof systems and cryptography. This quality makes them accessible to the public despite their many layers of complexity.

By the time the Zodiac began his killing rampage in 1968, ciphers and other cryptograms had invaded pulp crime novels and detective magazines. Readers could learn organizational tricks, such as the knight’s tour or period-19 transposition, and then use them in ciphers of their own. The Zodiac himself likely came of age reading some of those detective magazines and codebooks, says James R. Fitzgerald, a forensic linguist and criminal profiler who spent much of his career at the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit. “If Zodiac is ever identified and his house is ever searched, you’re going to find dozens and dozens of other codebooks, other pads of paper with other code written on them,” he says. “He had an extended interest in this kind of language usage.”

According to Fitzgerald, the Zodiac’s schematics align with popular cryptology strategies of the time. The first cipher was simple—a substitution code containing 26 symbols, each of which stood in for a letter in the English alphabet. Donald Harden, a high school teacher, and his wife, Bettye, solved it within a week of its publication. The couple estimates that they spent about 20 hours on the puzzle. They zeroed in on easy-to-find words likely to be used by a murderer; “kill,” for example, has repeating letters. Then they followed rules known to any Wheel of Fortune fan: namely, that E is the most used letter in the English language, as are certain letter pairings, such as T-H and Q-U. The solution read, in part:

I LIKE KILLING BECAUSE IT IS SO MUCH FUN. IT IS MORE FUN THAN KILLING WILD GAME IN THE FOREST BECAUSE MAN IS THE MOST DANGEROUS ANIMAL OF ALL. TO KILL SOMETHING GIVES ME THE MOST THRILLING EXPERIENCE. IT IS EVEN BETTER THAN GETTING YOUR ROCKS OFF WITH A GIRL. THE BEST PART OF IT IS THAT WHEN I DIE I WILL BE REBORN IN PARADICE AND ALL I HAVE KILLED WILL BECOME MY SLAVES.

At first glance, the cipher solution may seem worthless when it comes to catching a serial killer. Not so, says Fitzgerald. Instead, he points to the combination of literary allusion (most notably to Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game”) and colloquial sexual boasts as helpful context for a detailed psychological profile of the killer. So, he says, does the deliberate misspelling of “paradise” and the contrived idea of a specific afterlife awaiting the Zodiac.

“He didn’t believe any of it,” says Fitzgerald of the Zodiac’s claims. “Yet it gave him an ostensible rationale behind his killing, so he would not be seen by the public as just randomly and purposelessly choosing his victims.”

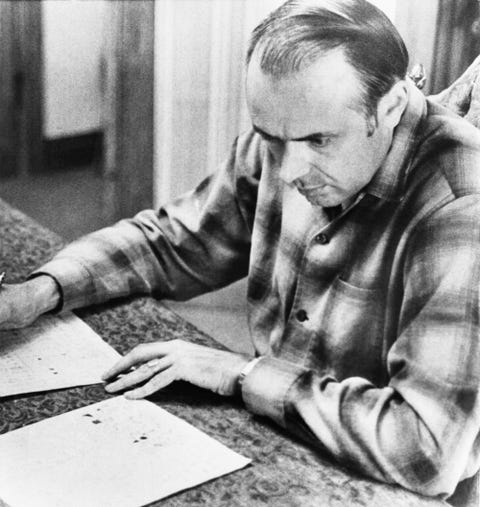

Donald G. Harden, a schoolteacher living in Salinas, California, broke the Zodiac’s first cipher sent on July 31, 1969, with his wife, Bettye June Harden

Getty Images

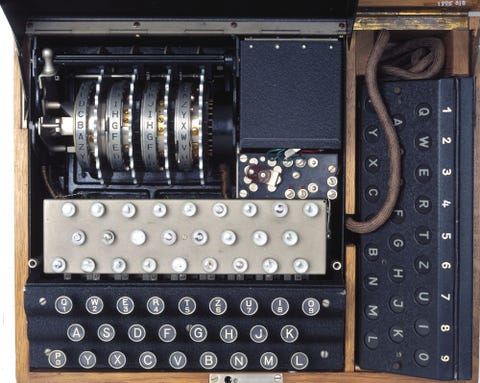

The code wheels and lampboard from a four-rotor German Enigma machine made during World War II, for which the user had to know the specific key settings used by the transmitter to decrypt a message

Getty Images

**Behavioral criminologists who have** worked the Zodiac case surmise that the 340’s construction was informed by the ease with which the first cipher was solved—a real blow to the killer’s inflated ego. For the 340, the Zodiac increased the number of individual characters to 50 and organized them via a far more complicated cryptogram. The cipher relied upon homophonic substitution, which assigns multiple symbols to a single letter and helps mask common letter pairings. As the cipher’s key—cryptology speak for a solution—continued to elude investigators at the FBI and NSA, cryptanalysts began to suspect that the Zodiac had somehow rearranged the order of the symbols, too, possibly including purposeful mistakes in the cipher that would confuse straightforward solutions—“a code within a code,” says Fitzgerald. He says the Zodiac, in this respect, fancied himself a kind of criminal mastermind. “The true code writer is very rare, even rarer among serial killers or serial offenders. And the ones that are difficult to break are the rarest of the rare.”

The ready solution to the first cipher might have led the killer to overcomplicate the second, including the usage of what Fitzgerald calls “false flag mistakes” to throw off codebreakers. “He wanted to become more of an enigma that he already was,” Fitzgerald says. “He thrived on that. This guy wanted to put himself above and beyond all those pedestrian-type killers.” This egotism might have also informed the Zodiac’s moniker, symbol, and costume, which eyewitnesses said resembled that of a medieval executioner. It’s also why he seemed to thrive on sending mail to newspapers and demanding airtime from TV programs. On one such show, a man claiming to be the Zodiac phoned in to say that his only worry was eventually being taken to the gas chamber, a fear inconsistent with the killer’s supposed megalomaniacal arrogance. Sure enough, the caller was later proved to be a fraud.

The Zodiac affected a persona who not only delighted in taunting authorities, but who also became bored with killing and needed to invent games to keep himself amused. The cipher is the primary symbol of the killer’s paradoxical needs to be both obsessed about and unknowable. That twisted psychology contributed to its immense difficulty, and is one reason why it took decades to unpack.

> “Zodiac killed for thrill, the ciphers only added to the thrill, once the killings became routine.”

**As COVID lockdowns** persisted in 2020, Jarl Van Eycke continued to refine his codebreaking software, AZDecrypt. He reported to Zodiac listserv users that it was becoming faster and more efficient, and he was adding features that allowed users to freeze keywords in the cipher, such as “kill,” while running permutations on the other symbols—a process called “cribbing” that can narrow the number of possible combinations a program needs to try. On his YouTube channel, Dave Oranchak theorized that the Zodiac had probably used a combination of schemes in the 340, including the knight’s move, in which a message is rearranged in a manner following the moveset of a knight in chess, and period-19 transposition, in which each character is moved 19 positions in the cipher before solving.

That video caught the eye of Sam Blake, a quantitative analysis researcher at the University of Melbourne. Burned out from his work in computing infrastructure, Blake found Oranchak’s channel a more relaxing way to problem solve. He joined the Zodiac hunt with traditional pen and paper at first, but found it “clunky” for interacting with the more complex schemes AZDecrypt was dealing with. Period-19 transposition in particular, he says, “seemed like a pain in the butt.”

Oranchak began working on the 340 in 2006 and posted his first YouTube video on his efforts in April 2020. That first video debunked writer Robert Graysmith’s proposed solution to the cipher, and in December that same year, Oranchak released the solution that he helped to obtain. That video has over 2 million views to date.

PETER MEANS/VTE

Blake commented on Oranchak’s video that it would be easy to enumerate the geometry of period-19 transposition into a computer program, but by that point Oranchak’s videos received dozens of comments a day and Blake’s mathematical suggestion was lost in the shuffle. But he kept at it until he found Oranchak’s email address and proposed his idea directly. Oranchak was impressed, and invited Blake to join him in the hunt for a solution.

Using the University of Melbourne’s supercomputer, Spartan, in conjunction with AZDecrypt, Blake and Oranchak parsed thousands of variations for the 340 cipher. Beyond period 19 and the knight’s tour, they tried other arrangements, such as alternating the cipher’s columns or organizing it along diagonal lines. Each new organization required multiple subvariations, such as moving each character 18 or 20 spaces instead of the traditional 19. It took hours, sometimes days, for AZDecrypt to churn through each possible solution. This methodology would’ve been impossible in 1969. “Homophonic substitution needs a really robust computer program,” says Blake. “I was able to create many different candidate ciphers because I had access to Spartan.”

Nevertheless, despite all the programming power at its gates, the cipher didn’t yield. Occasionally, AZDecrypt would reveal a single word and compel the codebreakers to dig deeper, but everything led to a dead end. The team began breaking the cipher into sections and applying different solutions to different sections, but even that failed. Months passed. The team soon amassed over 650,000 tested variations, but no answers.

While Oranchak and Blake attacked the cipher, Van Eycke kept improving AZDecrypt. Oranchak wondered if they’d actually tried the right variation already but that it just hadn’t been caught by an earlier version of the software. They began rerunning all 650,000 combinations again, with Oranchak hanging out in his wood-paneled office with the family’s Labrador, watching the program and waiting for it to produce a viable solution. About halfway through the rerun, he spotted fleeting words and phrases that hadn’t turned up during the first pass. In one variation, he found this fragment: *hope you are trying to catch me*. That seemed promising. Then he caught another phrase: *gas chamber*.

Oranchak used AZDecrypt’s crib feature to lock in those words, the same phrase the Zodiac impostor had used on TV in 1969, and then continued rerunning the variations. Eventually the program cracked the first section of the cipher. “That’s when I fell out of my chair,” Oranchak remembers. “I think I scared my dog.” The remaining two sections soon followed. They needed to be massaged and corrected in places, but at long last, the Zodiac’s message emerged before the codebreaker’s eyes:

I HOPE YOU ARE HAVING LOTS OF FUN IN TRYING TO CATCH ME

THAT WASNT ME ON THE TV SHOW

WHICH BRINGS UP A POINT ABOUT ME

I AM NOT AFRAID OF THE GAS CHAMBER

BECAUSE IT WILL SEND ME TO PARADICE ALL THE SOONER

BECAUSE I NOW HAVE ENOUGH SLAVES TO WORK FOR ME

WHERE EVERYONE ELSE HAS NOTHING WHEN THEY REACH PARADICE

SO THEY ARE AFRAID OF DEATH

I AM NOT AFRAID BECAUSE I KNOW THAT MY NEW LIFE IS

LIFE WILL BE AN EASY ONE IN PARADICE DEATH

**Most experts, including** the FBI’s crypto unit, agree that Oranchak and his team cracked the 340. Like the first cipher, it reveals a beguiling combination of high and low diction, spelling mistakes, and vague imaginings of immortality. Also like the first cipher, it lacks a hard clue as to the Zodiac’s identity.

But James Fitzgerald says that even the 340’s variations and mistakes hold valuable information for forensic linguists, including possible hints at the writer’s race, ethnicity, age, and gender. Criminals are better at inserting purposeful mistakes than at hiding lifelong linguistic habits. In the case of the 340 cipher, Fitzgerald believes the Zodiac tried to upgrade his language to look more sophisticated than he is, by way of antiquated diction like “all the sooner” and “paradice.”

He also suggests that both ciphers contain contraindicators, or statements that represent the opposite of what is true to the Zodiac. In other words, Fitzgerald asserts that the Zodiac never hunted wild game, never or rarely had sex, and was, in fact, terrified of dying. “Bottom line, Zodiac killed for thrill,” he says. “It was mentally, physically, and sexually empowering for him, all of which were missing from his everyday life. The ciphers only added to the thrill, once the killings became routine.” Fitzgerald predicts that behavioral scientists at the FBI will glean more information through further study of the ciphers.

Jim Clemente, a former FBI profiler, agrees. “Zodiac is nothing more than a vulnerable narcissist,” he says. “He was attempting to show how smart he is \[through the ciphers\], but he’s actually giving us evidence to take him down.”

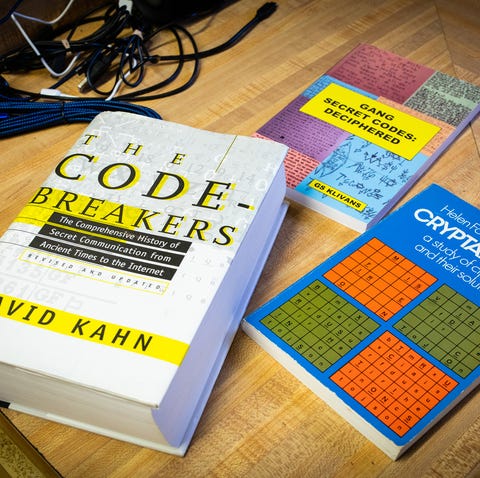

Materials from Oranchak’s collection of cryptography texts. Oranchak, Blake, and Van Eycke combined their skills in programming and mathematics with their interest in traditional cryptography to solve the 340 cipher.

PETER MEANS/VTE

After solving the cipher, Oranchak, Blake, and Van Eycke received medals from the FBI’s cryptanalysis unit.

PETER MEANS/VTE

> “In his zeal to create a more difficult puzzle, the Zodiac overextended himself and delivered a cipher that was almost impossible to solve.”

The mechanisms of the 340 itself possibly reveal the Zodiac’s limitations as a code writer. The cipher follows a variation of the knight’s tour and period-19 transposition, but the alterations to each of these schemes are idiosyncratic and sloppy. “We almost didn’t find the solution because of them,” Oranchak says.

Francis Heaney, a puzzle expert, calls the 340 a “read-my-mind” puzzle. “Basically, \[it’s when\] you’ve got an idea for a puzzle and there’s no way to solve it unless the person has the same idea,” Heaney says.

For example, the Zodiac altered his diagonal schematic in a seemingly random manner. He intended the six characters in the center-right of the cipher, which spell out “life is,” to be extracted from the diagonal and added to the end of the translated cipher. There’s precedent for that; some puzzles have “meta-answers,” an extra step after computation to reach the complete puzzle’s final conclusion (like when themed crossword clues must be rearranged to solve a riddle). But fair puzzles communicate the need for that extra step through what Heaney calls “breadcrumbs.” The Zodiac left no such instructions. “There’s not a lot of rhyme or reason to it,” Heaney says of the 340. “It’s a little bit free-form, which makes it very impressive that anyone solved it.”

In his zeal to create a more difficult puzzle, the Zodiac overextended himself and delivered a cipher that was almost impossible to solve—not because of any masterful underlying mechanism, but because the cipher lacked a discernible logic and structure.

The best puzzles build incrementally upon themselves, explains Heaney. They may include multiple different steps, but those layers should be iterative. Zodiac’s layers were haphazard at best. Solvable puzzles, even challenging ones, hint at their schematics through “flavor text”—proactive hints at a ski slope if, say, the puzzle follows a diagonal pattern. Heaney says inventive puzzlers also build difficulty through focus. The Zodiac sprawled in his methods, shifting the 340 abruptly between simple and homophonic substitution, utilizing multiple transpositions, and inserted a baseless meta answer. Based on the Zodiac’s profile, particularly his relentless thirst for attention, he wanted his ciphers to be solved and his message of terror out in the world. These inconsistencies, in that context, constitute a failure.

Without the computing power of Blake’s supercomputer and Van Eycke’s AZDecrypt to overpower the Zodiac’s unfair schematic, the 340 probably would have remained unsolved. And even though cracking the cipher revealed little biographical information about the killer, Oranchak thinks their methodology can lead to newer, faster ways of enumerating and substituting, which will allow other ciphers to be solved more quickly than under previous methods. “We live in an age of cryptography that is virtually unbreakable,” Oranchak says. “But so are these old-school codes.” Many unsolved puzzles continue to elude simple solutions, and some of these are connected to crime. “We need a better tool that can figure out what bucket a cipher belongs in before putting all that effort into breaking it.”

Cryptological progress, Blake says, will require experts and intelligence agencies to think outside the box, collaborate and crowdsource, and be willing to test methodologies developed by amateurs and armchair detectives. That, says Mike Morford, author of *The Case of the Zodiac Killer*, is the single most exciting aspect of the 340 solution.

“It just proves that if you dig at something long enough and keep at it, whether it’s for 40 years, 50 years, there’s a chance that you can be part of the solution. These guys proved that,” he says. “Their work encourages people to keep digging into these old cases and not to give up.”

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

# Donald Trump and American Intelligence’s Years of Conflict

News Analysis

## The Poisoned Relationship Between Trump and the Keepers of U.S. Secrets

The F.B.I. search of Mar-a-Lago is a coda to the years of tumult between an erratic president and the nation’s intelligence and law enforcement agencies.

Credit...Brittainy Newman for The New York Times

Aug. 11, 2022

WASHINGTON— After four years of President Donald J. Trump’s raging against his intelligence services, posting classified information to Twitter and announcing that he took the word of President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia over that of his own spies, perhaps the least surprising thing he did during his final days in office was ship boxes of sensitive material from the White House to his oceanside palace in Florida.

[The F.B.I. search of Mar-a-Lago](https://www.nytimes.com/live/2022/08/08/us/trump-fbi-raid) on Monday was a dramatic coda to years of tumult between Mr. Trump and American intelligence and law enforcement agencies. From Mr. Trump’s frequent rants against a “deep state” bent on undermining his presidency to his cavalier attitude toward highly classified information that he viewed as his personal property and would occasionally use to advance his political agenda, the relationship between the keepers of American secrets and the erratic president they served was the most poisoned of the modern era.

Mr. Trump’s behavior led to such mistrust within intelligence agencies that officials who gave him classified briefings occasionally erred on the side of withholding some sensitive details from him.

It has long been common practice for the C.I.A. not to provide presidents with some of the most sensitive information, such as the names of the agency’s human sources. But Douglas London, who served as a top C.I.A. counterterrorism official during the Trump administration, said that officials were even more cautious about what information they provided Mr. Trump because some saw the president himself as a security risk.

“We certainly took into account ‘what damage could he do if he blurts this out?’” said Mr. London, who wrote a book about his time in the agency called “The Recruiter.”

During an Oval Office meeting with top Russian officials just months into his presidency, Mr. Trump revealed [highly classified information](https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/16/world/middleeast/israel-trump-classified-intelligence-russia.html?referringSource=articleShare) about an Islamic State plot that the government of Israel had provided to the United States, which put Israeli sources at risk and angered American intelligence officials. Months later, the C.I.A. decided to pull a highly placed Kremlin agent it had cultivated over years out of Moscow, in part out of concerns that the Trump White House was a leaky ship.

In August 2019, Mr. Trump received a briefing about an explosion at a space launch facility in Iran. He was so taken by a classified satellite photo of the explosion that he wanted to post it on Twitter immediately. Aides pushed back, saying that making the high resolution photo public could give adversaries insight into America’s sophisticated surveillance capabilities.

[He posted the photo anyway](https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/02/world/middleeast/iran-space-center-explosion.html), adding a message that the United States had no role in the explosion but wished Iran “best wishes and good luck” in discovering what caused it. As he told one American official about his decision: “I have declassification authority. I can do anything I want.”

Two years earlier, Mr. Trump used Twitter to defend himself against media reports that he had ended a C.I.A. program to arm Syrian rebels — effectively disclosing a classified program to what were then his more than 33 million Twitter followers.

If there is not one origin story that explains Mr. Trump’s antipathy toward spy agencies, the [2017 American intelligence assessment](https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/06/us/politics/russian-hack-report.html) about the Kremlin’s efforts to sabotage the 2016 presidential election — and Russia’s preference for Mr. Trump — played perhaps the biggest role. Mr. Trump saw the document as an insult, written by his “deep state” enemies to challenge the legitimacy of his election and his presidency.

Image

Credit...Saul Martinez for The New York Times

Mr. Trump’s efforts to undermine the assessment became a motif in the early years of his presidency, culminating in a [July 2018 summit in Helsinki](https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/16/world/europe/trump-putin-summit-helsinki.html) with Mr. Putin. During a joint news conference, Mr. Putin denied that Russia had any role in election sabotage, and Mr. Trump came to his defense. “They think it’s Russia,” Mr. Trump said, speaking of American intelligence officials and adding, “I don’t see any reason it would be.”

Mr. Trump often took aim at intelligence officials for public statements he thought undermined his foreign policy goals. In January 2019, top officials testified to Congress that the Islamic State remained a persistent threat, that North Korea would still pursue nuclear weapons and that Iran showed no signs of actively trying to build a bomb — essentially contradicting things the president had said publicly. [Mr. Trump lashed out](https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/30/us/politics/trump-intelligence-agencies.html), saying on Twitter that “The Intelligence people seem to be extremely passive and naive when it comes to the dangers of Iran. They are wrong!”

“Perhaps Intelligence should go back to school!” he wrote.

Mr. Trump was hardly the first American president to view his own intelligence services as enemy territory. In 1973, Richard M. Nixon fired Richard Helms, his spy chief, after he refused to go along with the Watergate cover-up, and installed James Schlesinger in the job with the mission of bringing the C.I.A. in line.

Speaking with a group of senior analysts on his first day, Mr. Schlesinger made a lewd comment about what the C.I.A. had been doing to Mr. Nixon, and demanded that it stop.

Chris Whipple, an author who cites the Schlesinger anecdote in his book “The Spymasters,” said there is a long history of tension between presidents and their intelligence chiefs, but that “Trump really was in a league of his own in thinking the C.I.A. and the agencies were out to get him.”

The exact nature of the documents that Mr. Trump left the White House with remains a mystery, and some former officials said that Mr. Trump generally was not given paper copies of classified reports. This had less to do with security concerns than with the way Mr. Trump preferred to get his security briefings. Unlike some of his predecessors, who would read and digest voluminous intelligence reports each day, [Mr. Trump generally received oral briefings](https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/21/us/politics/presidents-daily-brief-trump.html).

But for those charged with protecting secrets, there may have been no bigger challenge than the seaside resort where Mr. Trump spent so much of his time as president — and where so many boxes of classified material were stored after he left office. Besides its members, Mar-a-Lago is also open to members’ guests, who would often interact with Mr. Trump during his frequent trips to the club. Security professionals saw this arrangement as ripe to be exploited by a foreign spy service eager for access to the epicenter of American power.

One night during his first weeks in office, [Mr. Trump was at Mar-a-Lago hosting Shinzo Abe](https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/11/us/politics/donald-trump-shinzo-abe-golf-mar-a-lago.html), the Japanese prime minister, when North Korea test-fired a ballistic missile in the direction of Japan that landed in the sea.

Almost immediately, at least one Mar-a-Lago patron [posted photos](https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/13/us/politics/mar-a-lago-north-korea-trump.html) on social media of Mr. Trump and Mr. Abe coordinating their response over dinner in the resort’s dining room. Photos showed White House aides huddled over their laptops and Mr. Trump speaking on his cellphone.

The patron also published a photo of himself standing next to a person he described as Mr. Trump’s military aide who carries the nuclear “football” — the briefcase that contains codes for launching nuclear weapons.

Just two world leaders responding to a major security crisis — live for the members of Mr. Trump’s resort to watch in real time.

# How Bolivia’s ruthless tin baron saved thousands of Jewish refugees

Moritz Hochschild was constantly on the move. In the early 1930s, he could be found in the grand hotels of London, New York or Paris, or on the back of a mule, following rough mountain trails in search of mineral seams in the Bolivian Andes. It was on one of those trips to a remote mountain village, according to family legend, that the mining magnate came across a local man sketching. The artist was afraid to show Hochschild his drawing, which was an unflattering caricature of him. But the magnate found the parody so amusing that he decided to fund a scholarship for the artist to study draughtsmanship in Paris.

Hochschild could afford to laugh at his own expense. His shrewd risk-taking had made him one of the richest men in South America in the early 20th century, and earned him notoriety as one of Bolivia’s three “tin barons”. The trio – Hochschild, Simón Patiño and Oxford-educated Carlos Aramayo – had made fortunes trading Bolivian tin which, during the first half of the 20th century, was much in demand for aeroplane parts and food cans, and accounted for more than half of the country’s export earnings.

The barons were seen as a cartel: “a circle of oligarchs who negotiated between themselves and had more power than the state,” the Bolivian historian Robert Brockmann told me. Tin was Bolivia’s principal mineral export in the 1930s, and the tin barons controlled 72% of the nation’s tin exports, while paying just 3% of their profits to the government. The three mining barons are chiefly remembered for their ostentatious wealth, their influence over Bolivian politics and their exploitation of mineworkers. “\[Hochschild\] was a cruel businessman; the toughest of the three,” Edgar Ramírez, former union organiser and archivist, told me. “The president of Bolivia wanted to have him shot.”

Hochschild, the youngest “baron” by decades, was the only one who was not a Bolivian citizen. A middle-class German Jew born in 1881 in Biblis, a small town south of Frankfurt, Hochschild sought his fortune in Australia and Chile before the first world war, returning to South America as soon as the war ended to build his metals and mining empire. During the 1930s and 40s, Bolivia was swept by waves of social upheaval. Amid mass demonstrations for state control of resources, Hochschild was twice thrown in jail and threatened with execution. He escaped with his life, but fled into exile. As the country hurtled towards the National Revolution of 1952, one of its chroniclers, Augusto Céspedes, described Hochschild as a “grand pirate of mining finances”.

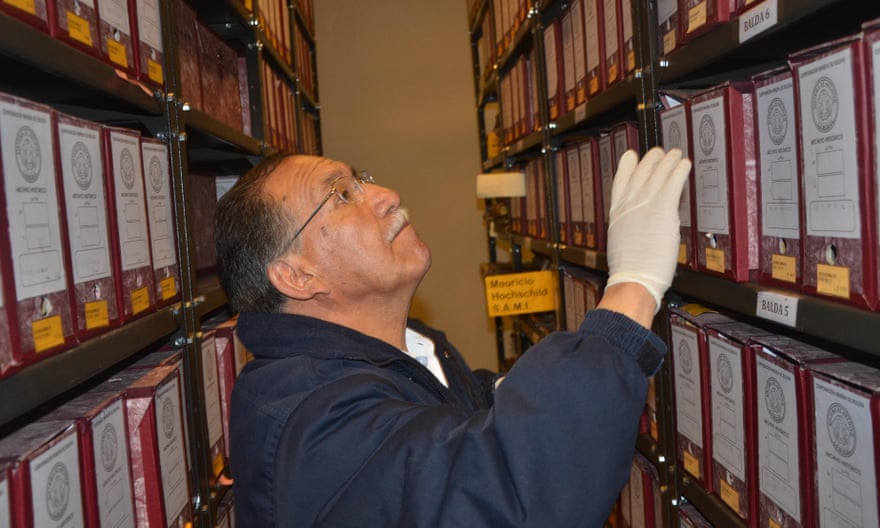

But evidence has since come to light that has forced Bolivia to reappraise its view of Moritz, known as “Mauricio” Hochschild. In 1999, several tonnes of rotting papers were found in warehouses owned by the state mining company, Comibol, which had taken over all of Bolivia’s mines when the industry was nationalised following the 1952 revolution. Documents from Hochschild’s companies [were discovered](https://networks.h-net.org/node/23910/blog/research-corner/5679375/el-alto-bolivia-ex-miners-rescue-their-history-part-i-s) piled in cardboard boxes, stuffed into barrels or dumped outside, exposed to the elements. Bolivia’s congressional library recognised the historical value of the archive, and a team was hired to organise the documents under the direction of Edgar Ramírez and the historian Carola Campos, who is now the archive’s director.

Get the Guardian’s award-winning long reads sent direct to you every Saturday morning

In 2004, after five years of sorting through thousands of pages of correspondence with consulates, businesses and international Jewish organisations, the team revealed their astonishing discovery. The papers demonstrated that Moritz Hochschild had helped to rescue as many as 22,000 Jews from Nazi Germany and occupied Europe by bringing them to Bolivia between 1938 and 1940, at a time when much of the continent had shut its doors to fleeing Jews. The documents, which included work permits and visas for European Jews, tracked Hochschild’s efforts not only to ensure Jews escaped Europe but also to resettle them in Bolivia, investing his own fortune and using his influence with the country’s elite to secure protection and employment for as many refugees as possible.

“This aspect of the man was unknown until we discovered these papers,” Edgar Ramírez told me in October 2020. Ramírez, a union man of 74 who still wore his flat cap and workman’s overalls, grew up in Potosí, a mining town where Hochschild employed hundreds of miners on near-starvation wages. “\[He\] was known in Bolivia as the worst kind of businessman. The worst!” Ramírez growled. “But who was the real Hochschild?”

---

After the first publication of their findings in 2004, Edgar Ramírez’s team of investigators continued to make more discoveries, and in 2005, documents surfaced in warehouses in El Alto, the satellite city of Bolivia’s administrative capital La Paz. In 2009, further south, in the mining towns of Oruro and Potosí, work permits for Jewish refugees were found scattered among the files of Hochschild’s multiple companies. In 2016, Unesco recognised the archive’s historic value and added it to the Memory of the World Register; as a result, Hochschild’s humanitarian work became more widely known. The legacy of Mauricio Hochschild, until then, had been his immense wealth; his villainous reputation, according to Brockmann, had served the architects of the 1952 revolution as a “necessary part of the nation-building myth”.

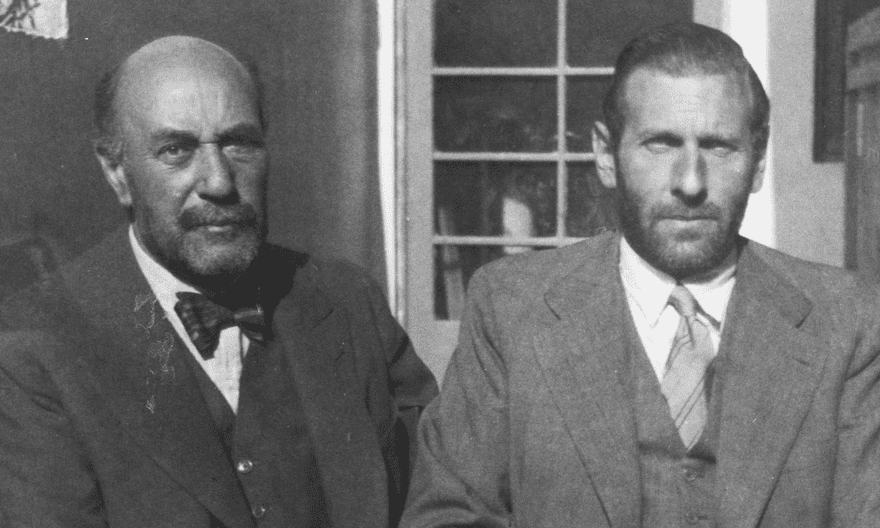

Hochschild was a towering figure. Bald-headed and moustachioed, with bushy eyebrows that framed expressive brown eyes, he resembled an “Old Testament patriarch” according to his employee and later biographer, Gerhard Goldberg. When he first started his mineral explorations, Bolivia was underpopulated and much of the country was not industrialised. Don Mauricio, as he was known, belonged to a generation of early 20th-century Europeans who believed nations could be transformed through capitalism. He mingled with Bolivia’s patrician classes and its military top brass, and sought favour with the clergy by generously donating to Catholic charities. “He possessed enormous charm and a great ability to attract people. Of this he was well aware,” wrote Goldberg. “When there were problems, his favourite reaction was ‘Let me talk to him’, and most of the time he proved capable of persuading people, often against all expectations.”

In 1929, Hochschild founded the South American Mining Company. Demand boomed from Europe and the US for metal ores, and by 1937, he controlled around a third of Bolivia’s tin production, and around 90% of lead, zinc and silver exports. He used European connections to push markets in London, Germany and the Netherlands and made frequent trips to the old continent.

A disused tin mine on the Cerro Rico mountain, Bolivia. Photograph: Sebastien Lecocq/Alamy

As Hochschild’s business went from strength to strength in South America, the systematic persecution of German Jews was intensifying. Between 1933 and 1935, he was approached by international Jewish organisations for help, according to Brockmann, and told them that Bolivia did not have the economic capacity to receive a large number of refugees. The political turmoil in Bolivia at that time was intense, and he may have suspected – as indeed it turned out – that his own position was not secure.

But when the young war hero Lt Col Germán Busch took power in a military coup in July 1937, the two men formed a bond. “They met many times. In fact, Hochschild considered him a friend,” said Brockmann. “\[Hochschild\] was a man very close to power. He was sent to the US to negotiate the price of tin, invested with diplomatic status.”

By then, much of South America was aligned with Europe’s fascist leaders. Busch, aged just 34 when he became president, was half German, and his father, a German doctor, supported Hitler. Still, Hochschild managed to persuade Busch that Bolivia’s economy could gain from opening its doors to Jewish fugitives – although Busch insisted his country did not need city folk, but farmers. In March 1938, Busch signed a resolution ordering consular officials to allow Jews to enter Bolivia, particularly if they could be “useful to national activities”. Three months later, he issued a decree permitting “all men of sound body and spirit” to enter Bolivia, offering farmland and inviting immigrants to populate its “barren lands”. “In Bolivia, we should not partake in hatred and persecution,” the decree read.

“When the news reached the cities of Europe occupied by the Nazis, enormous queues immediately formed outside the Bolivian embassies and consular offices,” said Brockmann. A network of corrupt consular officials, led by the Bolivian foreign minister, took advantage of the wave of Jewish families desperate to leave Europe to charge thousands of dollars for visas and passports. (When the scandal became public in 1940, the foreign minister was forced to resign.) “Between 1938 and the first months of 1940, a breathtaking number of Jews arrived in Bolivia - somewhere between 7,000 and 22,000,” Brockmann added. A letter written by Hochschild to Edwin Goldwasser of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee in March 1939 said Busch had agreed to “gradually receive 10 to 20,000 German Jews, with the priority of colonization, on the condition that enough money is made available \[by the committee\]”.

Hochschild leaned on Busch to ensure that the visas would be respected once refugees arrived in South America. Ramírez said that the tycoon, who was unable to travel to Europe in person, “bribed \[officials\] to buy blank passports”, and through his links with anti-fascist resistance groups, oversaw the creation of false agricultural work permits and identities for fugitives.

Correspondence with Hochschild’s staff in 1939 showed detailed plans for a *Hilfsverein*, or a welfare association for Jewish migrants, and the disposal of $30,000 of company funds for the arrival of an initial 1,000 people. Adding a $137,500 donation from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, Hochschild created the Society for the Protection of Israelite Immigrants, known as Sopro in its Spanish acronym. The funds paid for a 20-bed hospital, a children’s home and a kindergarten in La Paz, and even a retreat in Cochabamba for Jews suffering from altitude in the city.

[Map of Bolivia and neighbouring countries showing the rail route carrying refugees](https://interactive.guim.co.uk/uploader/embed/2022/08/bolivia-refugeesmap/giv-65628pCjnPYSEjdg/)

Thousands of European Jews appeared in the steep, narrow streets of La Paz and Cochabamba, where the refugees started businesses selling hot dogs, tailoring or dry-cleaning. When local people found themselves having to compete for jobs, or being priced out of rented accommodation by the new arrivals, an antisemitic backlash began. [Refugees](https://www.theguardian.com/world/refugees) were abused on the streets, and the attacks were fuelled by antisemitic editorials in the press. Under pressure from Busch to ease tensions in the cities, Hochschild bought three agricultural estates in the high jungle region of Yungas, and founded the Bolivian Settlers Society, which managed farming projects for Jewish immigrants relocated to the countryside. The archive contains dozens of work permits registering German and Austrian Jews as agricultural labourers. But many of the new arrivals were merchants, doctors, lawyers, teachers or musicians who had no idea how to farm.

Hochschild’s immigrant farming venture was ultimately a failure but it served a short-term purpose – the deliverance of thousands of Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany. Most longed to return to life in the city, and after the war left Bolivia for Israel, the US or cities in Brazil and Argentina. A smaller number of Jews were already working for Hochschild’s mining companies on meagre wages, as León E Bieber, 79, a Jewish Bolivian historian and author of a 2015 book about Hochschild, told me when we met in Santa Cruz de la Sierra. “They worked mostly administrative posts,” Bieber said, “and for Hochschild, this was important because he trusted in these people’s honesty. He paid miserable salaries compared to what he could have paid. This shows he was first and foremost a businessman who wanted to get the best out of his people.”

---

One of the children that Moritz Hochschild saved from the Nazis was Ellen Baum de Hess, now 94. “He was a true hero,” she told me over the phone from Buenos Aires, where she has lived for the past 80 years. In 1938, when she was just 10, Baum de Hess and her mother fled Berlin, having recently witnessed Kristallnacht, the infamous pogrom against Jews, which heralded what the future held for them in Germany. She recalls walking home from school and seeing “a synagogue burning and the broken windows of many Jewish businesses” in Berlin the following day. “That was when my mother realised that we had to get out of Nazi Germany,” she told me.

At the time there was a two-year waiting list for US visas, which also required an American financial sponsor, preferably a relative. Baum de Hess’s parents were separated, and all she and her mother were able to get was a tourist visa for Uruguay. In late December 1938, they boarded a steamship, the General San Martín, in Boulogne, in northern France. But when they arrived in Uruguay’s capital, Montevideo, more than a month later, customs officials refused to let them disembark, claiming their tourist visas were fake. Baum de Hess remembers the adults pleading, desperate to be allowed ashore, even though they suspected that the country’s government sympathised with the Nazis, or had been ordered by Nazi Germany to turn back Jews fleeing Europe. “Many of the 28 people \[on board\] wanted to throw themselves into the ocean because we were desperate. We didn’t want to go to a concentration camp,” she said. From Montevideo, they sailed to Buenos Aires, arriving in late February 1939, where they were held in port for three weeks before being sent back across the Atlantic.

Ellen Baum de Hess with her family in Mar de Plata, Argentina, 1957. Photograph: Courtesy of Ellen Baum de Hess

The ship docked in Lisbon in April 1939, and while awaiting news of their fate, the passengers received reason to hope. There were rumours aboard about a mysterious well-wisher who had managed to get them visas to Bolivia. “People said there was a benefactor,” Baum recalls, “who, through his friendship with the Bolivian president, had managed to get visas for us. We were told that the only one who could have achieved that was Moritz Hochschild.”

After another three weeks in Lisbon, the passengers got word that they had been granted safe passage. They were ferried to the Italian port of Genoa and, from there, aboard another ship, the Orazio, set sail once again for South America. The refugees docked at Arica in northern Chile, the main port of entry for landlocked Bolivia, in the middle of June 1939. From there, they reached Cochabamba by train, said Baum de Hess. The rail route into Bolivia became known as the *Express Judío*, or Jewish Express, due to the huge influx of refugees. (Months later, in January 1940, the Orazio – carrying more than 600 mostly Jewish refugees – caught fire and sank in the Atlantic Ocean. Passing ships were able to rescue most of the passengers, but more than 100 died.)

Baum de Hess and her mother stayed in a village near Cochabamba for more than a year before making their way to Argentina, where her aunt awaited them. They did not have a visa, but crossed Bolivia’s southern border into Argentina where they boarded a train bound for Buenos Aires in December 1940. Her family could not afford to pay for her schooling beyond the age of 13, but she trained as a secretary and, owing to her command of German, Spanish and English, worked as a translator. “With very little schooling, I became self-educated,” she declared with a triumphant laugh. “I, my mother and the other 26 people owe \[Hochschild\] our lives, although no one knew at the time.”

---

A year after the president had opened Bolivia’s doors to Jews fleeing Nazi persecution, as Europe was on the brink of war, Busch and Hochschild’s relationship soured. In June 1939, Bolivia’s mining companies were given four months to hand over their foreign currency reserves to the national mining bank, which would return the funds in local currency. Hochschild, the most stubborn of the tin barons, refused to comply. Busch had an “attack of rage”, according to historian Herbert Klein, and sentenced the tycoon to go before a firing squad, before intercessions from his ministers, the US and Argentina spared Hochschild this fate.

Two months later, Busch, who had a history of depression, shot himself. Earlier that night, he had reportedly complained about the number of Jews in the cities when he had expected farmers in the fields, Brockmann said. Busch’s supporters, made suspicious by the violent circumstances of his death, accused Hochschild and the other tin barons of plotting his murder. Half a year after Busch’s death, the country’s immigration commissioner suspended the visas allowing Jews into Bolivia but, despite heated – often antisemitic – debate over their status, the proposal was not ratified in the legislature. As late as March 1943, the government issued visas to around 100 Jewish orphans in France, according to historian [Florencia Durán](https://books.openedition.org/ifea/7298?lang=en), though by that stage, they were unable to get out of Europe.

During the war, Hochschild’s metals business became key to consolidating Bolivia’s strategic support for the Allies. He was already a key broker for Bolivian tin with the US, so was well placed when vast quantities of the metal were needed to make ammunition boxes, aeroplane instrument panels and syringes to administer morphine. In 1940, Hochschild brokered a deal between Bolivia and the US Metal Reserve Company to supply tin at 48.5 cents per pound, which boosted production but soon fell below market price. In 1942, the price rose to 60 cents, and Bolivia’s profits fell.

Another cache of documents indicates that Hochschild himself was a committed supporter of the Allied war effort. Comibol archivists showed me a blacklist of hundreds of Bolivian-based businesses with German, Japanese and Italian names. Dated from November 1939 to August 1946, the file, labelled “Trading with the Enemy”, compiled by the US embassy and the British legation in La Paz, contained a regularly updated list of firms with possible fascist sympathies or ties. Letters show Hochschild was an enthusiastic enforcer of the veto, writing cordial but forceful letters to trading partners to ensure they upheld the ban or lose his business.

In 1943, a pro-fascist military dictator, Col Gualberto Villarroel, took power in a coup, and pushed for Bolivia to switch from supporting the Allies to the Axis powers. One of the reasons Villaroel toppled his predecessor was the unfavourable tin price that the mining magnate had negotiated with the US. Hochschild became one of Villaroel’s “bêtes noires”, said Brockmann, “because he was rich, capitalist, Jewish and foreign”. In May 1944, Villarroel had Hochschild arrested, accused of treason and threatening the stability of the government, and he was jailed for 45 days, along with one of his managers, Adolf Blum. But “even behind bars”, [Time Magazine](https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,850499,00.html) reported, “Don Mauricio was still a power-center of Bolivian politics”. After pressure from the US, Chile and Argentina, he was released. In July 1944, an ultra-nationalist, pro-fascist military faction, known as Razón de Patria, kidnapped him, and Blum, and held them for 17 days. “The rebels were inspired by mixed motives of nationalism and social reform. \[Hochschild\] has been unpopular on both counts,” reported Newsweek.

Moritz Hochschild (left) and Adolf Blum after being released by kidnappers in La Paz in 1944. Photograph: Leo Baeck Institute, New York

“They kidnapped him with the intention of killing him, to send a message to the world: ‘This is what we do with the Jewish capitalist foreigners’,” said Brockmann. For Hochschild, it was the second time he had faced death after falling foul of a military president. After the kidnappers released him, in August 1944, he fled Bolivia on a Chilean government plane, never to return. A few days later, he told the [New York Times](https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1944/09/06/87467325.html?auth=login-email&pageNumber=11) he could not discuss the details of his release, only that no ransom had been paid. He made a statement to the effect that he had never plotted against the Bolivian government and “he hoped to help Bolivia adjust its postwar social and economic problems”. He also wanted to reassure the US that the kidnapping incident would not interfere with the “steady flow of Bolivian tin from his mines to American smelters”.

Hochschild’s company retained control of his Bolivian mines, and his international business continued to thrive. He moved to Chile, where years later he opened Mantos Blancos, a hugely successful copper mine in Antofagasta.

“When Bolivia turned against him … it must have been extremely painful,” said his grandson Fabrizio Hochschild Drummond, 59 – a former UN official whose employment recently ended after [allegations](https://apnews.com/article/technology-business-united-nations-antonio-guterres-cb2ccc5bbe049a3fe17c62c026551df0) of bullying – speaking to me on the phone from New York. “He had tried to give his heart and soul in turning this country around and it kicked him out, short of killing him.”

---

When I visited the neat, air-conditioned Comibol archive in El Alto, under a sign reading “Out of the trash, into the memory of the world”, three Bolivian archivists wearing blue rubber gloves and face masks were sifting through hundreds of yellowing pages of typed correspondence in German, Spanish, Hebrew and English. Among them, Ramírez, pointed out a handwritten letter addressed to Hochschild in neat calligraphy from a Jewish kindergarten in La Paz, asking for funds to build a second floor “in view of the number of children who are here and others who want to come”. He was already known to the children as the benefactor: the first floor of the school had been built by his charitable organisation. The letter, which is believed to date from 1944, includes a black-and-white photo of the students and staff, and is signed by “the children”.

After years of poring over evidence of Hochschild’s good works, Edgar Ramírez had revised his opinion of Hochschild’s legacy. He told me he now considered Hochschild a heroic figure. It was his view that the tycoon concealed his “true face” – that Hochschild was, in fact, an unsung leader in the international anti-fascist resistance. Months after my visit to El Alto, Ramírez, the driving force in the Comibol archive, died from a Covid-related illness. For more than two decades, he had led the team of archivists that conserved and restored hundreds of thousands of work and personal documents relating to Hochschild, which now fill 50 metres of specially constructed shelves.

Edgar Ramírez, then director of the Bolivian mining archive in El Alto, in 2017. Photograph: Dpa Picture Alliance/Alamy

Researchers are still puzzling over the apparent disparity between the public businessman and the private humanitarian. Ricardo Udler, a spokesman for Bolivia’s small Jewish community, believes Hochschild deliberately kept his activities quiet in order to operate more effectively. “Many people whose families arrived in Bolivia didn’t know that their benefactor was Hochschild. When the Comibol archive was opened, only then did many people in the community begin to investigate and realise what this figure, Hochschild, had done. He had been working silently, bringing many, many people. By keeping a low profile, he probably managed to get more people out.”

Before the second world war, records show there were no more than 100 Jews in Bolivia, yet by the 1940s there were some 15,000, according to Udler, a medical doctor and president of El Círculo Israelita de Bolivia, the association of the once-thriving Jewish community. The country’s current Jewish population stands at little more than 300 and is shrinking, he explained, and there is now just one rabbi in the whole country. “It is important that our children know about one of the great saviours of our history,” said Udler, 64, whose French-Polish mother survived four concentration camps before escaping across the Atlantic to Bolivia.

---

Just down the corridor from the Comibol archive is an imposing mural by local artists William Luna Tarqui and Jesús Callizaya, which commemorates the 1952 Nationalist Revolution. The fresco, which lionises socialist ideals, revolutionary leaders and ordinary workers, follows a Latin American tradition exemplified by the Bolivian *Indigenista* painter Miguel Alandía Pantoja, whose art was, by turns, glorified and vilified by successive dictatorships. The revolution resulted in the nationalisation of the tin barons’ mines – including Hochschild’s – who was compensated with 30% of the company’s prior assets.

During the revolution, Hochschild was portrayed in plainly antisemitic terms, cast as the capitalist villain who used “Judaic trickery to stretch his hand over the biggest mines,” in the words of Augusto Céspedes, a writer who championed the upheaval. While Hochschild had “unmatched personal influence with Bolivian authorities in the highest ranks of government and the armed forces”, writes Leo Spitzer, in Hotel Bolivia, a book about his childhood in Bolivia as the son of Austrian Jews, “his foreign birth – and, no doubt, the fact he was also a Jew (albeit a non-practising one) – also generated intense jealousy and dislike among some Bolivian nationals.”

A mural depicting Bolivia’s 1952 revolution at the Comibol archive in El Alto, Bolivia. Photograph: Vanett Graneros/Wikimedia

Among the hundreds of Jewish families that Hochschild gave new life and hope, many did not realise until recently that they were part of a bigger group of beneficiaries. One of them is Fred Reich, 73, a retired businessman and an important figure in Peru’s 2,500-strong Jewish community in Lima. His father, Kurt Reich, was an Auschwitz survivor from Austria who got his first job, aged 26, as a messenger boy for Hochschild’s company in La Paz, in March 1947. “Only after Mauricio’s death, people have realised the amount of fantastic work he did to save Jews from the horror of Europe,” said Fred Reich at his home overlooking the Pacific Ocean in Lima’s bohemian Barranco neighbourhood. “At that time, to the best of my knowledge, it was only known that he was very sympathetic to hiring Jewish people in Bolivia.”

While working for Hochschild, Kurt Reich had discovered that one of the accountants had been stealing from the company, and reported the theft. When he heard about Reich’s action, Hochschild, who was in Paris at the time, invited him for lunch. “Going to Paris would be like going to the moon today,” Fred recounted proudly. “You have to imagine: La Paz to Rio, Rio to Casablanca, Casablanca to Lisbon, Lisbon to Paris – in small planes!” Hochschild was impressed that his father had survived the camp, said Fred. “At one point he \[had\] weighed 32kg, so it was quite a miracle for him to be alive.”

Hochschild promised to pay for Kurt Reich’s son’s education anywhere in the world, and Kurt went on to have a long and successful career at the company. Hochschild’s pledge was fulfilled after his death when Fred went to study at Alfred University in New York state. Fred Reich still has the letter Hochschild wrote to his father in German, telling him of his plans to visit the family in Arequipa, Peru. But Fred never got the chance to thank the man he calls the “Bolivian Schindler”. Hochschild died alone aged 84 in June 1965 in Le Meurice, a five-star hotel in Paris. His remains were interred in the Père Lachaise cemetery.

Even Hochschild’s family did not seem to have made much of his humanitarian work. Growing up in wealthy circles between London and Santiago de Chile, Fabrizio Hochschild Drummond remembers his grandfather’s achievements on the mining front were vaunted, but what he had done on behalf of the Jews was “really barely mentioned”. “I had heard stories of how he brought Jews from Germany,” said Hochschild Drummond, “but it was always presented to me, when I was a child, that it was more \[for\] self-interested business reasons rather than \[something\] altruistic and praiseworthy. So when the story came fully to light about five years ago, I was taken aback, not by the fact but by the scale.

“I remember in Chile coming across many strangers who, once they had my surname, would tell me how my grandfather had helped them at this or that time in their life.” He believes his grandfather’s deliverance of thousands of Jews from the Nazis was a “great act which has never fully been recognised”.

Follow the Long Read on Twitter at [@gdnlongread](https://twitter.com/@gdnlongread), listen to our podcasts [here](https://www.theguardian.com/news/series/the-long-read) and sign up to the long read weekly email [here](https://www.theguardian.com/info/ng-interactive/2017/may/05/sign-up-for-the-long-read-email).

This article was amended on 12 August 2022 to revise reference to the allegations against Fabrizio Hochschild Drummond.

Credit...Photo illustration by Najeebah Al-Ghadban

Published Aug. 3, 2022Updated Aug. 11, 2022

### Listen to This Article

*To hear more audio stories from publications like The New York Times,* [*download Audm for iPhone or Android*](https://www.audm.com/?utm_source=nytmag&utm_medium=embed&utm_campaign=mag_screenland_the_bear)*.*