49 KiB

| Tag | Date | DocType | Hierarchy | TimeStamp | Link | location | CollapseMetaTable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2023-08-22 | WebClipping | 2023-08-22 | https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2023-sherman-apotex-billionaire-murder/ | true |

Parent:: @News Read:: 2023-09-12

name Save

type command

action Save current file

id Save

^button-WhoMurderedBarryShermanandHoneyNSave

Who Murdered Apotex Pharma Billionaire Barry Sherman and Honey?

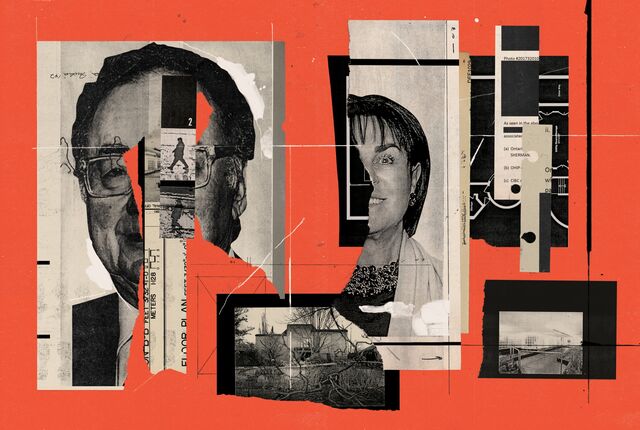

Photo illustration by Mike McQuade; photos: Barry and Honey Sherman: George Pimentel. House: Fred Lum/the Globe and Mail

Murder, Money and the Battle for a Pharmaceutical Empire

Almost six years after Barry and Honey Sherman became two of the wealthiest people ever to be murdered, police still haven’t identified the killers. But along the way, they’ve turned up no shortage of potential suspects—and a bare-knuckle family drama.

August 3, 2023, 12:01 AM UTC

The call came in to the Toronto police homicide squad on a chilly December afternoon. A man and woman had been found dead at a home in an upmarket suburban neighborhood, posed in a horrifying tableau. They were side by side at the edge of an indoor pool, held up by leather belts looped around their necks and tied to a metal railing. By the time the first officers arrived, in response to a 911 call from a real estate agent who was showing the house, rigor mortis had set in, indicating they’d been dead for hours.

Brandon Price, a young homicide detective with sharp features and close-cropped brown hair, drove to the scene. The house was thick with people: uniformed constables to establish a perimeter, forensic specialists to comb for evidence, a coroner to prepare the remains for transport to an autopsy. An officer took photos, documenting the location and condition of the bodies as well as the state of the many other rooms.

The Shermans' house at 50 Old Colony Rd. in Toronto. Photographer: Fred Lum/the Globe and Mail

Outside was a growing number of journalists, dispatched as word filtered out about the identities of the deceased. They were Barry and Honey Sherman, one of Canada’s wealthiest and best-known couples and the residents of the house. Barry, 75, was the founder and chairman of Apotex Inc., a large generic pharmaceutical producer. His net worth was estimated at $3.6 billion at the time of his death in 2017. He and Honey, 70, used that money to become major philanthropists, donating generously to charities, cultural institutions and Jewish causes. They weren’t the richest people in Canada, but they were as prominent as anyone, appearing at seemingly every charity gala in Toronto and known to have strong connections to the Liberal Party of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. Autopsies would determine that both of the Shermans had died from “ligature neck compression”—strangulation. They were among the wealthiest murder victims in history.

Price and his colleagues have been investigating the Shermans’ deaths for more than five years, alongside private detectives hired by the couple’s adult children: Lauren, who’s now 47; Jonathon, 40; Alexandra, 37; and Kaelen, 32. In that time no one has been arrested, let alone charged. A representative for the Toronto Police Service declined to comment on the specifics of the investigation but said that it remains active and that it would be inaccurate to describe the murders as a cold case. They’re nonetheless an enduring mystery. Who had a motive to kill both Sherman and his wife? Why would that person choose such a gruesome method? And how did they cover their tracks so effectively?

Even though the police and the private team haven’t identified suspects, they have turned up a great deal about the Shermans and their world. Most of their findings were unknown when Bloomberg Businessweek last covered the case, in 2018. They’ve been revealed for this story through legal filings, private documents, interviews with people familiar with the relevant events—who declined to speak on the record about private matters—and a cache of police materials released following petitions from the Toronto Star. As investigators dug into the Shermans’ past, they uncovered a family drama rife with vendettas and grudges, accusations and rumors, centered on a dominant patriarch and a next generation vying for his favor.

With Barry Sherman gone, that drama entered a new, bare-knuckle phase. Suddenly inheriting his empire, his children made it clear that their priorities differed from their father’s. They broke with his and Honey’s closest confidants and began making plans to sell off Apotex, the company Sherman had devoted his life to building. Then, some of them turned on each other.

In the summer of 2017, Apotex had a liquidity problem. A judge in Ottawa had just ruled against the company in a legal battle with AstraZeneca Plc, the UK-based pharma giant, which had accused it of infringing on patents for the heartburn drug Prilosec. The decision would require Apotex to pay about C$300 million ($227 million), equivalent to its entire annual budget for developing new products. To some extent, such courtroom losses were a hazard of doing business. Generic drug makers routinely introduce new products “at risk,” putting them on sale while they seek to invalidate the original drug’s patent in court. If the generic producers fail, they’re ordered to pay damages. If they win, they keep the revenue from the initial sales.

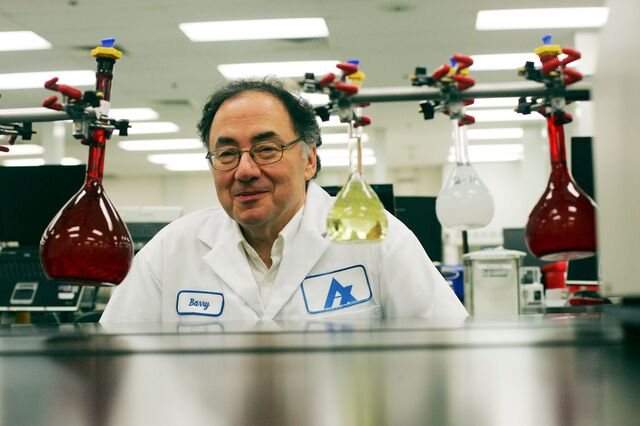

Sherman had engaged in dozens of similar legal battles in his long career. He was neither a lawyer nor a drug scientist. Rather, he had a doctorate in aeronautics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. But after an uncle died suddenly, leaving behind a small generic drug company called Empire Laboratories, Sherman returned to his hometown of Toronto and took over. He sold Empire after six years and used the proceeds to set up Apotex in 1974.

Heavyset and bespectacled, Sherman turned out to have a ferocious talent for the generics industry, and particularly for patent challenges. He spent much of his time on litigation, astonishing his attorneys by reading every brief they prepared. When Apotex lost a case, an appeal was a foregone conclusion: Sherman almost always fought to the end. He built the company into Canada’s top drug manufacturer, responsible for filling 1 in 5 domestic prescriptions, without going public or taking outside investment, leaving him in complete control.

Sherman didn’t always act like the billionaire he was. His and Honey’s home, while large and comfortable, wasn’t in a particularly prestigious neighborhood. He drove a series of beat-up cars, wore ancient, frayed dress shirts and often ate at Swiss Chalet, a chicken chain where combo meals cost less than 15 bucks. What he enjoyed most was work, and he had an almost bottomless capacity for it, rarely taking a day off and dispatching emails at all hours. At the downtown charity functions he attended with Honey, the main decision-maker for the couple’s philanthropic endeavors, he mostly talked business.

Although Sherman wasn’t Apotex’s chief executive officer—that was a British scientist named Jeremy Desai—he had the final say on big decisions. His style could be idiosyncratic. When a publicly listed company is engaged in a major legal case, it often makes a provision for the potential loss and plans its finances accordingly. Sherman preferred to wait until defeat was certain. Only then would he instruct his lieutenants to get the cash together, tapping his personal holdings if necessary. It was a risky strategy, but Sherman was confident he’d never be short.

Still, the AstraZeneca judgment represented a huge hit, and it came at a time when Sherman faced significant demands on his funds. Apotex was planning a $184 million research and manufacturing hub in Florida while simultaneously considering a costly expansion of its Canadian production lines, something the patriotic Sherman considered a legacy project. He and Honey were also working with designers to plan a new house in tony Forest Hill, just north of downtown Toronto, where she wanted to move. Another line item related to Honey, too: Despite Sherman’s great wealth, she had relatively little in her own name, leaving her dependent on her frugal husband. Sherman was moving toward transferring a significant portion of his assets to Honey, which she’d be free to use as she wished.

Sherman in a lab at his pharmaceutical company, Apotex. Photographer: Jim Ross/the New York Times/Redux

One of Apotex’s most powerful competitors, Israel’s Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., had also opened a new and potentially expensive legal front. In a lawsuit filed in Pennsylvania federal court in July 2017, Teva claimed that Desai, the Apotex CEO, had been having an affair with a Teva executive who’d passed him confidential documents about products. Apotex and Desai denied acting improperly. The matter was still enough of an embarrassment that Sherman’s advisers urged him to get rid of Desai, but he refused, and it appeared no one at Apotex could change his mind.

A further drain on Sherman’s resources was the multitude of relatives, friends and hangers-on who’d tapped him for money over the years. For the most part he was happy to oblige, underwriting everything from homes to dubious investment ideas. According to police documents, Sherman bought a house for a daughter’s brother-in-law and a C$1 million savings bond for her mother-in-law. For his son’s boyfriend, he bankrolled a real estate business and provided a monthly stipend that continued even after the couple broke up. Sherman also gave about C$8 million in assistance to a cousin, Kerry Winter, whose late father had founded Empire Laboratories. (Winter later sued Sherman, claiming unsuccessfully that a long-dormant financial provision entitled him and his siblings to 20% of Apotex.)

Then there were the four children themselves. Sherman was often absent when they were young, missing family dinners and sports events to be at the office. He was more generous with his money than his time, and he funded the lifestyles and business ventures of all four kids. Despite Sherman’s wishes, none was interested in working for Apotex, and he could be uncharitable in assessing their characters, telling friends and colleagues he was disappointed by their choices. (He was slightly less critical of Alexandra, who’d trained as a nurse.) After the Shermans were killed, a relative would tell police that the couple “had some frustrations with their children because of their lack of work ethic, because the children were raised in and exposed to a lot of money.”

Honey’s relationship with the kids could be particularly strained. She was outspoken to the point of abrasiveness. After Jonathon came out as gay in high school, she struggled to hide her discomfort with his sexuality. Sherman was more accepting. Honey periodically urged him to cut back on his financial support for the children, to encourage them to be more independent. But he generally refused.

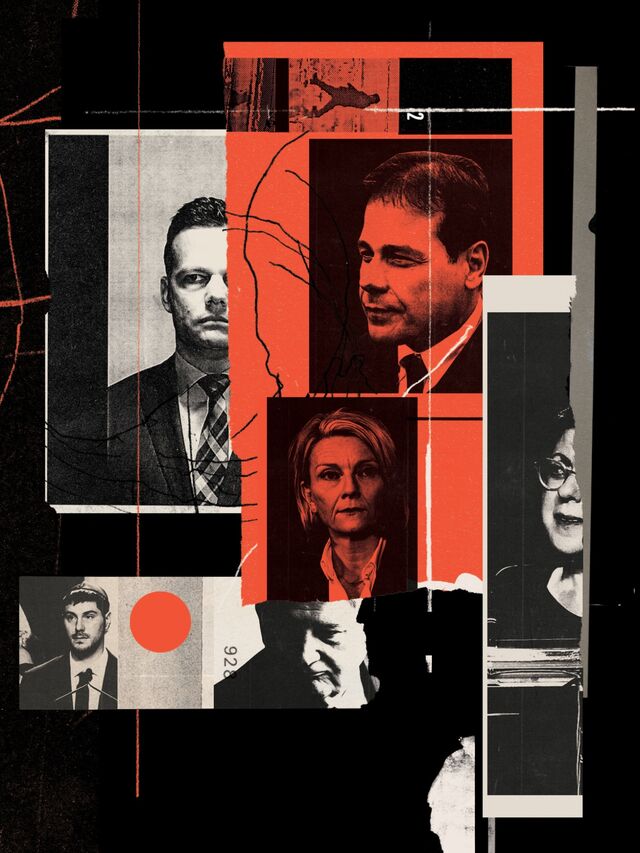

Jonathon Sherman speaking at the memorial service for his parents. Photographer: Nathan Denette/the Canadian Press/AP Photo

Some of Sherman’s largest checks went to two people: Jonathon, who had more of an interest in business than his siblings, and Frank D’Angelo, a flamboyant entrepreneur whom Sherman met in the early 2000s. For Jonathon, Sherman backed Green Storage, a self-storage operation Jonathon ran with a childhood friend. Land-title records show that at the time the Shermans died, Green Storage had received C$135 million in low-cost loans from a company called Hour Holdings, which, according to a person with knowledge of the matter, Sherman had entirely funded.

D’Angelo had investments in restaurants, brewing, energy drinks and film production; most were unprofitable. An internal tally prepared by Sherman’s colleagues and reviewed by Businessweek shows that Sherman extended hundreds of low-interest loans to D’Angelo’s company from 2003 to late 2017. Almost nothing was repaid. The individual loans were typically small, often only a few hundred thousand dollars, but the document shows that by the end of Sherman’s life, the total sum was more than C$268 million, including interest.

D’Angelo, who didn’t respond to a detailed list of queries from Businessweek, is something of a comic figure in Toronto, with a persona that seems drawn in equal parts from Goodfellas and Slap Shot. Among other endeavors, he’s known for a late-night TV vehicle called The Being Frank Show and for producing B movies with names such as Real Gangsters and Sicilian Vampire. What Sherman saw in D’Angelo was a matter of speculation for those around him. Some concluded that Sherman, an archetypal nerd, relished hanging out with a back-slapping guy’s guy who was friendly, in turn, with figures such as Phil Esposito, the legendary Boston Bruins center. (In Canada, NHL players qualify as meaningful name drops.)

According to people familiar with the situation, Jonathon tried for years to persuade his father to stop supporting D’Angelo, who, he argued, was taking advantage of Sherman—not to mention squandering money that might have gone toward the children’s inheritance. Others, including Jack Kay, Sherman’s longtime right-hand man, also urged him to cut off D’Angelo. But Sherman bristled at Jonathon’s criticism, describing him as “petulant” for questioning his decisions. Matters became tense enough that at one point, Jonathon suggested he might seek a medical determination that his father—viewed as an intellectual titan by virtually everyone who worked with him—was incompetent to manage his own affairs. Sherman found the idea ridiculous, and the confrontation blew over. (A representative for Jonathon declined to comment, apart from a statement that Jonathon “remains committed to working with his siblings, furthering his parents’ legacy of charitable giving and community service, while also supporting the ongoing criminal investigation.”)

The mid-2017 AstraZeneca defeat forced Sherman to reevaluate his spending. Right after the ruling he emailed Jonathon and his business partner, telling them he was “reluctant” to advance more money to their ventures in the short term. In a message later that year he urged the pair to quickly arrange bank mortgages, “to enable repaying 50-60 million.” But Sherman emphasized that the constraints were temporary: “I am certain that we will be able to advance further substantial funds to you, if wanted for further investments, beginning in 2019.”

With D’Angelo, Sherman took a harder line. “Losses of 500,000 per month appear to be endless. Despite endless assurances that we are now doing well. Where is it all going??” he asked in a September 2017 email. D’Angelo wrote that business “is just coming around. It’s on a tight rope.” Less than two weeks later, D’Angelo copied Sherman on a discussion of revenue shortfalls in his film and drinks businesses. “Our timing is beyond brutal!” he complained. “Our Movie Sicilian Vampire is No. 1 movie on Mexican t.v. & we are in this situation. I’m reading Fox the f---en riot act this Thursday.”

In response, Sherman said he’d had enough of D’Angelo’s requests for cash. “I have been providing funds month after month for years, averaging close to $1 million per month,” he wrote. “Approximately every 2 weeks, I get another request for funds, because some expected revenue is late, but in reality it is to cover endless losses. There have been countless assurances of various good things that were imminent, but almost nothing has materialized.” He continued: “I will not be able to provide further funding beyond the end of this year, so we need to decide what to do with each division individually.”

Police outside the Shermans’ house after their bodies were discovered. Photographer: Chris Helgren/Reuters

From the moment the Shermans’ housekeeper, Nelia Macatangay, arrived at 50 Old Colony Rd., early on Friday, Dec. 15, 2017, she started noticing unusual things. In the three years she’d worked for the couple, the burglar alarm had always been on when she arrived in the morning. Now it was off. Nor was there any sign of Sherman, whom Macatangay usually found in the kitchen. He and Honey didn’t appear to be home, and Macatangay began cleaning.

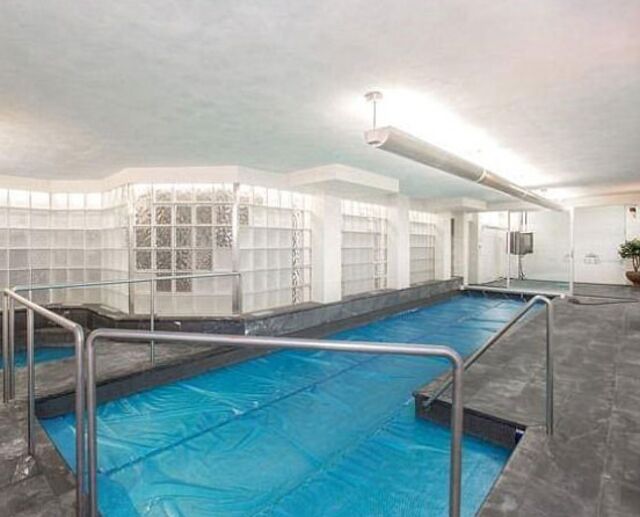

The Shermans’ real estate agent, Elise Stern, arrived and began giving a tour of the house to a couple who were considering buying it. Stern was leading everyone into the basement pool room when she saw the bodies slumped on the far side of the deck. She later told police she initially thought the Shermans might be doing “some sort of weird meditation or yoga,” but she soon realized something was amiss and hustled the prospective buyers out. Stern then asked Macatangay to go down and look. “I am sure I saw them in the basement,” she said. “Something happened.” Frightened, Macatangay refused. The family gardener, who was also in the house, offered to go down instead. She came back upstairs shaking.

The Sherman case landed that afternoon with a team led by Detective Sergeant Susan Gomes, a veteran cop of almost 30 years. But it was Price, a much younger detective, who went to the scene and was assigned as the primary investigator, under Gomes’ supervision. Speaking to reporters outside the Sherman home that night, Price made a comment the Toronto police would come to regret. “I know that an event such as this can be very concerning to the community,” he said. “I can say that at this point in the investigation, though it is very early, we are not currently seeking or looking for an outstanding suspect.” Partly, according to a person familiar with the investigation, Price made the statement to calm fears in the neighborhood. There’d been a number of recent break-ins, and police wanted to avoid panicking residents. But the implication of his remarks was clear, and local papers began reporting that detectives suspected Sherman could have murdered Honey, then killed himself.

Gathered with their loved ones at Alexandra’s house, the Shermans’ children refused to accept this notion. Their parents were rich, in relatively good health and delighted by their expanding ranks of grandkids. Sherman sometimes joked that he intended to live forever, because the world couldn’t go on without him. The children decided the police were heading down the wrong path. Within a day they’d hired Brian Greenspan, a celebrated Canadian criminal lawyer, who initiated a private investigation. Its first goal was straightforward: to prove Sherman wasn’t responsible for his and Honey’s deaths. Over the weekend, Greenspan began assembling a team of retired police led by Tom Klatt, a former Toronto homicide officer, and made plans for second autopsies of the bodies.

Whatever Toronto police suspected early on, they weren’t dismissing the possibility that both Barry and Honey had been murdered. Officers fanned out across the city, even searching the sewers around 50 Old Colony. They applied for warrants to search the Shermans’ electronic devices—Honey used a white iPhone; Barry, somewhat eccentrically, a BlackBerry—and compared crime-scene images with photos taken for the real estate listing, to determine whether anything valuable was missing. An officer lifted fingerprints from Honey’s Lexus SUV. Others sought seven years of the Shermans’ medical billing records, partly to determine whether either was “suffering from any undisclosed, terminal illness or any substantial pain which could alter their outlook on life,” as officers described their aim in a warrant document.

Sherman family lawyer Brian Greenspan. Photographer; Chris Young/the Canadian Press/AP Photo

Detective Brandon Price. Photographer: Rene Johnston/Toronto Star/Getty Images

Detective Sergeant Susan Gomes. Photographer: Chris Young/the Canadian Press/AP Photo

Detectives also attempted to reconstruct the couple’s final hours. They’d last been seen on the evening of Dec. 13, after a meeting with the team designing their new house. Sherman sent a routine email to colleagues shortly afterward, then went silent. No one heard from him or Honey the next day, a Thursday, even as their phones lit up with messages: photos from Alexandra, a holiday party invitation from Jonathon and notes from various Apotex executives. The unresponsiveness was extremely unusual, especially for Sherman, who tended to reply to emails right away.

The police interviewed a cross section of relatives, friends and associates. Price met early on with Kay, who was the vice chairman of Apotex and Sherman’s closest colleague. Kay rejected the suggestion that Sherman could be a killer. “Barry would never harm anyone,” he said, according to police notes. Alexandra told two other detectives that even though her parents had often quarreled when she was younger, in the past few years they were “a lot more in love and not arguing and spending more time together.” Jonathon provided a similar assessment and added that, to his knowledge, they’d never experienced mental health issues. At the same time, he said, “there are people out there who would have a grudge against them and would have a reason to hurt them.”

Just how abnormal a probe this was became even clearer after police visited Sherman’s office and removed his hard drive as evidence. The following day the Toronto force received an email from Goodmans, Apotex’s longtime law firm, warning that the computer and Sherman’s other electronics contained documents that were “highly confidential and proprietary to the company.” The lawyers demanded that the devices “be segregated and sealed” until they could establish a process for protecting corporate information. After discussions with government legal advisers, the police consented to a remarkable arrangement: Goodmans attorneys would get to read Sherman’s files first, then provide access only to material they’d determined wasn’t legally privileged.

The parallel private investigation was also highly unusual. Almost from the start, people familiar with the matter said, the family’s investigators believed the police were mishandling their inquiry. Most glaring was the suspicion of murder-suicide. The pathologist who conducted the first autopsy of the Shermans’ bodies had told Price that murder-suicide, double suicide and double homicide were all possibilities. And initial police warrant applications listed only Honey as a murder victim, while the nature of Sherman’s death was “unclear.”

For their own autopsy the private team hired David Chiasson, a doctor who’d formerly served as chief forensic pathologist for the province of Ontario. The day before the Shermans’ funeral, he examined their remains at the Toronto coroner’s complex while Klatt and others from Greenspan’s group looked on. According to the people familiar with the matter, Chiasson noted wide markings on the Shermans’ necks—the imprint of the belts that had tied them to the pool railing. But the belts, he thought, might not have been used to strangle them. Chiasson also observed another set of markings, which were narrower, as though from a cord or rope. No such item had been found. If Sherman had hanged himself from the railing, he would obviously have been unable to dispose of whatever had left the second set of markings. It was far likelier that someone had put him in that position. Greenspan’s team told the homicide squad about Chiasson’s findings right away and offered to have the pathologist brief police. But it was more than a month before Gomes, Price’s superior, met with Chiasson. Shortly after that, she announced in a press conference that the police now believed both Shermans were the victims of a targeted murder.

Basement Plan of 50 Old Colony Rd.

Source: 731, Houssmax

The force completed its searches of 50 Old Colony in late January, six weeks after the discovery of the bodies. Klatt was standing by with a group of retired forensic investigators to take over the scene. They conducted a fresh search for fingerprints and palm impressions and used a specialized vacuum to gather fibers that might not be visible to the naked eye. At more than 12,000 square feet, the home presented a complicated puzzle. For one thing, the pool wasn’t necessarily where the killings had occurred. The Shermans drove home separately on the night of Dec. 13, with Honey arriving first. It appeared that Sherman dropped his belongings just past the side door he’d used to enter from the sunken garage—perhaps the location where he was attacked. Honey’s iPhone, which she usually kept close at hand, was found in a ground-floor powder room that family members had never known her to use.

The pool at the Shermans’ home. Source: Realtor.ca

The private team didn’t have access to the same picture the police did. Its relationship with the force was chilly, with officers declining to provide even basic information. At the second autopsy, the pathologist who’d conducted the original postmortem had given Greenspan’s team a binder of crime-scene photos. When police officials learned of it, they demanded the images be returned. (Greenspan did so, though his group had already reviewed them.) It wasn’t merely that the Toronto cops resented being second-guessed; they saw no legal way to share evidence they’d gathered, and a defense lawyer would be sure to seize on any hint of an improper relationship. Using evidence from the outside investigators, they also feared, might leave them open to legal challenge.

Undeterred by the risks, the Sherman children continued to fund the investigation. For them, money wasn’t a problem.

Barry Sherman’s finances were complex. He had two wills, both executed in 2005. The first dealt with personal assets such as real estate, their value estimated by his trustees at around C$69 million. The second was for certain shares in privately held companies, including the entities that controlled Apotex. (The wills were made public after a reporter for the Star, Kevin Donovan, sued to force their disclosure, in a case the Sherman estate appealed all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada.) But the bulk of Sherman’s wealth resided in a pair of trusts, set up to transfer money to family members over time. One listed only his and Honey’s children as beneficiaries; the other allowed for discretionary distributions to additional relatives and their descendants. In most scenarios, however, the four Sherman kids would receive the largest portion of the assets.

It was clear Jonathon would play a role in managing the family’s riches. In addition to being the most business-oriented of his siblings, he was one of four trustees of his father’s estate, along with Kay; Alexandra’s then-husband, Brad Krawczyk; and Alex Glasenberg, who managed the family’s holding company, Sherfam. With Sherman gone, the trustees were formally in charge of Apotex.

One of the first major changes there came in late January 2018, when Desai, whom Sherman had refused to fire after Teva’s corporate espionage allegations, left the company. Desai would tell police that without Sherman he “did not have the protection or support” to continue in his role.

That left the question of broader corporate strategy. Focused on long-term growth, Sherman had maintained research and development spending at a considerably higher level than industry peers. And his plans for expanded manufacturing, including the new plant in Florida and more production lines in Canada, would require major commitments of capital. Although it was a big drugmaker in Canadian terms, Apotex didn’t have the global scale of rivals such as Teva, and according to colleagues, Sherman had figured he’d have to sell his company eventually. But he’d wanted to do so only after implementing his vision.

By March 2018, Jonathon and his sisters had made a formal determination to sell Apotex much sooner. In a memo to the trustees, they said their wish was to exit the business “as quickly as possible (9-18 months max), and for the highest possible value,” so they could free up cash to “fully fund” their future charitable endeavors. As a prelude to executing those instructions, Apotex slashed R&D expenses, looked for assets to unload and put investment plans on hold. It would ultimately sell the Florida site at a loss.

Not all the trustees were happy with the strategy. Kay had worked alongside Sherman since the early 1980s. They had adjacent offices, separated by a short hallway, and had spent thousands of hours together, often in good-natured debates about religion and other topics. Kay wanted to stick to Sherman’s plans, people familiar with the matter said, convinced that the idea of selling earlier would have horrified his friend. Meanwhile, the people said, Jonathon bristled at Kay’s decision, some months after the murders, to move down the hall into Sherman’s former office. Kay presented the change as practical, allowing Apotex to free up space. But Jonathon interpreted it as overreach.

In December 2018, shortly before the first anniversary of the killings, Jonathon asked Kay for a meeting. He was polite but firm, informing Kay that his employment at Apotex was over. The next day his office access would be gone. Although Kay was clearly upset, he seemed resigned to the situation; he and Jonathon had been at odds for months. He soon walked out to his car.

That wasn’t the only close relationship that didn’t survive the Shermans’ deaths. At their memorial service, held in a cavernous convention hall and attended by about 6,000 people, Jonathon had announced a plan to honor his parents’ philanthropic legacy. “We would like to announce the creation of the Honey and Barry Foundation of Giving,” he said in his eulogy. He envisioned a role for Honey’s sister, Mary Shechtman: “We would also like to ask our Aunt Mary … to help guide this foundation in a way that best honors our parents.”

But the children ended up severing links with Shechtman, their mother’s closest confidant. Money was one of the main causes of the estrangement. Soon after the murders, according to people with knowledge of the matter and correspondence seen by Businessweek, Shechtman began claiming that Honey had intended to leave her hundreds of millions of dollars—much or even all the money Sherman had been moving to transfer to his wife. Shechtman repeated the claim over the following months and also requested other assets, including jewelry and real estate. Honey “wanted me and my children to get everything of hers,” Shechtman wrote in one email. “She knew the value of her entire estate would be minimal compared to what you and your siblings would inherit and none of you would need it financially.” (A representative for Shechtman declined to comment.)

Even if the transfer to Honey had occurred, she appears not to have had a will; none has been located. The money Shechtman said she was due was part of what the children were inheriting. Not surprisingly, they declined to give it to her. “I cannot willy-nilly give my sisters’ inheritance away simply because Mary claims it is hers,” Jonathon wrote in a message to his siblings.

Clockwise from top left: Price, D’Angelo, Shechtman, Greenspan and Jonathon Sherman, with Gomes in the center. Photo Illustration by Mike McQuade; photos: Price: Getty Images; Shechtman, Sherman: Nathan Denette/the Canadian Press/AP Photo; Greenspan: Chris Young/the Canadian Press/AP Photo; D’Angelo: Allison Jones/the Canadian Press/AP Photo

As the Sherman children tried to make sense of their new situation, police were investigating their parents’ financial relationships. With his combative style and a business model centered on grabbing revenue that would otherwise go to big drugmakers, Sherman had accumulated his share of enemies in the pharma industry. In an interview for Prescription Games, a 2001 book by Jeffrey Robinson, Sherman had said he wondered why a big drug company didn’t “just hire someone to knock me off.” He’d continued: “Perhaps I’m surprised that hasn’t happened.”

That was a touch dramatic—publicly traded corporations tend to prefer lawsuits to contract killings. And according to a person with knowledge of their investigation, no one in Sherman’s industry dealings stood out to police as a potential suspect. Nor were they certain, based on the crime scene, that the murders were the work of hired professionals. Paid hits in Canada, as in other Western countries, are typically carried out with a quick bullet or two to the head.

Several people in Sherman’s orbit instead became of considerable interest to detectives. The most obvious to them was Winter, the cousin who’d sued Sherman for a stake in Apotex. He was an early focus of the police investigation, the person with knowledge of it said, and Price interviewed him at length. Winter had made no secret of his anger toward Sherman, who, he claimed, had concealed an option agreement intended to benefit him and his siblings. A judge in Ontario’s Superior Court of Justice had thrown out Winter’s suit about three months before the Shermans were killed. Soon after their deaths, Winter told the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. that he’d previously fantasized about killing his cousin, saying Sherman would “come out of the building at Apotex … and I’d just decapitate him.” Winter added, “I wanted to roll his head down the parking lot.” (He declined to comment.)

Price and his team also looked into D’Angelo, whose unprofitable brewing, restaurant and film ventures Sherman had funded before threatening in late 2017 to end his support. (The Sherman estate would eventually write off D’Angelo’s debts, concluding there was no way to recover the money.) And they scrutinized Jonathon, who’d moved to put his mark on the family empire and was one of the main financial beneficiaries of his parents’ demise.

To establish whether any of the three could have been involved, police analyzed the records of phone numbers they were known to use, mapping their communications and whereabouts before and after the Shermans were killed. Officers also obtained “tower dumps”—data that show every device connected to a cell tower in a given period—for the area around Old Colony Road, as well as the places where the couple had been in the hours leading up to their deaths. Police could then check whether numbers came up that were linked to Winter, D’Angelo, Jonathon or other individuals on detectives’ radar—for example, by being registered to a business address associated with one of them. But the phone analysis and other police inquiries into the men didn’t turn up hard evidence, the person familiar with the probe said. Even if each of the three had a potential motive, detectives couldn’t link them to the crime.

In the autumn of 2018, more than 10 months after the murders, Greenspan called a press conference. Its purpose was partly to announce that the Sherman family had set up a tipline and was offering a reward of as much as C$10 million for information leading to charges. Greenspan indicated that he hoped the money would induce someone with inside knowledge to come forward. “And as they become wealthy, their colleagues who were engaged in this crime [will] become the subjects of a prosecution,” he said.

Greenspan also used the occasion to slam the police, citing the findings of his own investigators. Toronto officers, he said, had “failed to properly examine and assess the crime scene” and had “failed to recognize the suspicious and staged manner in which [the Shermans’] bodies were situated”—leading to the discarded suspicion of a murder-suicide. He claimed police had neglected to check all points of entry into 50 Old Colony and had missed “at least 25 palm or fingerprint impressions.” Greenspan said he was delivering his remarks in part “to light the fire” under the Toronto force, which was still refusing to cooperate with his group. He urged it to accept a “public-private partnership,” in which the external investigators would augment the resources of city detectives, and said his team’s evidence would stand up to scrutiny in a future trial.

Contrary to Greenspan’s wishes, the two investigations did not begin working more closely after his comments. If anything, the chasm widened. Out of view, the police did have an intriguing lead. Early in their investigation, officers had canvassed the Shermans’ neighborhood for surveillance footage taken around the time of the murders. (The couple had no working cameras on their own property.) Residents recognized everyone who turned up in the videos, with one exception: a lone figure in a winter coat and hat or hood who’d spent a curious amount of time close to the Shermans’ home.

A surveillance video still made public by police. Source: YouTube

The images were maddeningly poor, though. The person looked vaguely male—police began calling him the “walking man” in judicial documents—and appeared to stand between 5 feet 6 inches and 5 feet 9 inches. But it was impossible to make out his face or other details. His only distinctive feature was the way he walked, with a habit of kicking up his right foot with each step. Detectives found his behavior extremely suspicious—so much so that they said in warrant paperwork that their “investigative theory [is] that this individual is involved in the murders.” But they were unable to determine his identity.

By 2019 their investigation had been underway for more than a year, still with no arrests. The private probe was similarly inconclusive. The tipline Greenspan had set up did receive a large volume of calls. Inevitably, many were from cranks and purported psychics. Some were from people offering useful information. None was from the insider Greenspan had speculated might break the case open.

In early 2019, Alexandra stopped replying to calls and messages from Jonathon. Before then the siblings, who’d been close since childhood, had been in regular communication. For example, while Greenspan represented all four children, it was Jonathon and Alexandra who were functionally his clients, holding regular meetings with him. The eldest and youngest children, Lauren and Kaelen, weren’t deeply engaged with the private investigation.

Jonathon sent Alexandra a long email in April, headed “I miss you, please read.” He told her he’d “always counted you as my closest confidant, and I’m feeling pretty hurt that you don’t want to talk to me.” Jonathon continued: “If there is something I’ve done to upset you to the point that you won’t answer the phone when I call, could you please explain it to me?” Eventually he learned what had changed. Alexandra, four people with knowledge of her views said, had begun to think Jonathon might have been involved in their parents’ deaths. It’s unclear what drove her to that suspicion, and the police, according to the person with knowledge of their investigation, didn’t view it as being based on any evidence.

Alexandra hired her own lawyer, John Rosen, known for his work defending serial murderer and rapist Paul Bernardo. In August 2019, Rosen sent a letter to Greenspan. He wrote that Alexandra wanted Greenspan to “cease the parallel investigation and to deliver forthwith to the Toronto Police Service investigators a copy of your complete file.” In the meantime, Rosen said, Greenspan was “no longer authorized to publicly claim to represent her.” Although Jonathon wanted to keep working with Greenspan, the lawyer concluded it would be inadvisable to continue. His probe ended officially in December 2019, and its findings were turned over to the police. (A representative for Alexandra declined to comment beyond a statement that she remains “hopeful that the case will be solved” and urges anyone with relevant information to contact the homicide squad.)

At the same time as Jonathon’s relationship with Alexandra broke down, tensions were emerging between him and Glasenberg, the Sherfam manager. Originally from South Africa, Glasenberg had worked for Sherman since the 1990s and knew more about his business activities than virtually anyone. Jonathon, according to documents reviewed by Businessweek, argued that Glasenberg was refusing to share information to which he was entitled and was making key decisions without his input. (A representative for Glasenberg denied these claims and said he “has at all times acted fairly and appropriately in his dealings with Jonathon Sherman and has abided assiduously by his fiduciary and other duties.”)

Alexandra and her sisters sided with Glasenberg in what soon became a major rift. The situation worsened steadily through 2020, to the point that Jonathon threatened to go to court to press his grievances—litigation that would be sure to attract enormous media attention. Through their lawyers, the sisters suggested that if he did so, they might sue to remove Jonathon as an estate trustee. Before anyone filed a lawsuit, the four siblings agreed to professional mediation. The process eventually resulted in the appointment of a new board for Sherfam, including one representative nominated by each of the siblings. After being installed in mid-2021, the new board’s first task was to finally implement the decision the children had made three years earlier, and start a formal effort to sell Apotex.

Meanwhile the police kept investigating, offering no public updates about their progress. They were still trying to determine the identity of the walking man and getting nowhere. Price broke the silence in late 2021, releasing a brief video of the mysterious individual and appealing for citizens’ help in identifying him. Given that detectives had been aware of the person’s presence near 50 Old Colony since 2018, why had they waited this long to disclose the video? To critics, it appeared the force was trying to show that its investigation into a crime that remained a subject of fascination in Toronto hadn’t been completely fruitless. A more charitable interpretation would be that Price hoped to revive public interest and prompt some hitherto-unknown witness to reveal themselves.

Hank Idsinga, the current head of the homicide squad, has publicly emphasized that it’s not uncommon for complex murder cases to be resolved years after the fact. While the Sherman investigation remains live, it’s not nearly as active as before. Gomes, the original supervising detective, has been promoted and no longer works in homicide. Price was also promoted and is now a detective sergeant, with responsibility for the overall management of the Sherman file. Only one detective, Dennis Yim, is assigned to it full time. According to a person with knowledge of his work, Yim has recently been focused on probing Sherman’s financial dealings in the US, including through various shell companies and offshore entities. Still, the person said, detectives’ best hope at this point is that someone, somewhere, will come forward with information that leads to a breakthrough.

While the Shermans were alive, their children were part of a tight network of extended family, coming together for elaborate Jewish holiday celebrations that Honey threw at their home. Many of those bonds have now been broken. Although Jonathon and Alexandra live within a short drive and both have young kids of their own, they haven’t been on speaking terms since 2019. When they communicate, it’s through their attorneys. Alexandra has also split from her husband, and Kaelen divorced the man she married after the murders.

The efforts by the new Sherfam board to find a buyer for Apotex were successful, and last year the company announced it was being acquired by SK Capital Partners, a private equity firm based in New York. The price wasn’t disclosed, but people with knowledge of the transaction said it valued Apotex between C$3 billion and C$4 billion. Soon, Sherman’s principal asset would be turned into cash to be divided by his heirs. As the rest of Sherman’s estate is unwound, the financial affairs of his children will be increasingly unconnected from one another. (Lauren lives in British Columbia with her family. Kaelen has been active in Israel; according to the financial newspaper Globes, she spent $41 million for a 50% stake in a seaside Ritz-Carlton hotel in 2021.)

Jonathon has used some of his money to retain a second private investigator, a former Manhattan prosecutor named Robert Seiden, who’s said he chose a career in law enforcement because of the killing of his brother, a bystander in a 1980s mob hit. According to a person familiar with the assignment, however, Seiden is mainly on standby in case new information emerges, rather than leading a fresh probe.

In December, Alexandra marked the five-year anniversary of her parents’ murders with a press release, attributed only to her, that reiterated that the C$10 million reward “remains available and is still unclaimed.” A few days later, Jonathon made a separate announcement through the CBC. He said he was adding an additional C$25 million. —With Manuel Baigorri and Riley Griffin

More On Bloomberg

$= dv.el('center', 'Source: ' + dv.current().Link + ', ' + dv.current().Date.toLocaleString("fr-FR"))