11 KiB

| Tag | Date | DocType | Hierarchy | TimeStamp | Link | location | CollapseMetaTable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2022-10-30 | WebClipping | 2022-10-30 | https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/10/mississippi-welfare-tanf-fraud/671922/ | true |

Parent:: @News Read:: No

name Save

type command

action Save current file

id Save

^button-MississippisWelfareMessNSave

Mississippi's Welfare Mess—And America's

Mississippi Shows What’s Wrong With Welfare in America

Public officials plundered a system built on contempt for poor people.

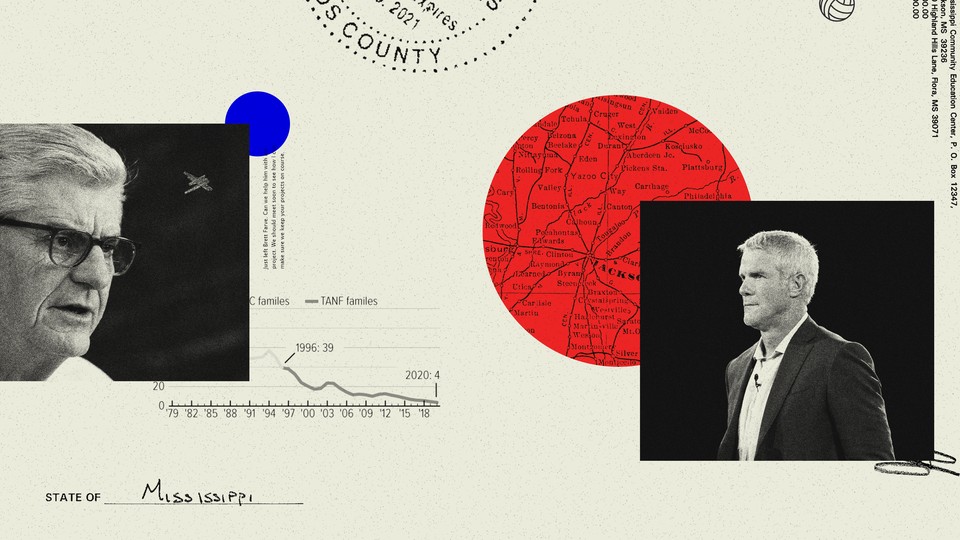

AP; CBPP; Getty; Joanne Imperio / The Atlantic

October 29, 2022, 6 AM ET

Writing out what happened in Mississippi, I am not quite sure whether to laugh or cry. Just before the coronavirus pandemic hit, then-Governor Phil Bryant schemed to loot money from a government program for destitute children and redirect it to Brett Favre, the legendary Green Bay Packers quarterback, as part of a ploy to get a new volleyball facility built at the university attended by Favre’s daughter.

That is just one of any number of jaw-dropping stories emerging from a massive state-welfare-fraud scandal, bird-dogged by tenacious reporters, including Anna Wolfe and Ashton Pittman. Over the years, Mississippi officials took tens of millions of dollars from Temporary Assistance for Needy Families—the federal program frequently known simply as “welfare”—and wasted it on pointless initiatives run by their political cronies. Money meant to feed poor kids and promote their parents’ employment instead went to horse ranches, sham leadership-training schemes, fatherhood-promotion projects, motivational speeches that never happened, and those volleyball courts.

The scandal is a Robin Hood in reverse, with officials caught fleecing the poor to further enrich the wealthy, in the poorest state in the country. It is also an argument for ending welfare as we know it—really, this time, and not just in Mississippi. I’m not talking about telling needy families to fend for themselves. I mean that the United States should abandon its stingy, difficult means-tested programs and move to a system of generous, simple-to-access social supports—ones that would also be harder for politicians to plunder.

Danté Stewart: The irony of Brett Favre

Politicians and administrators looted the Mississippi TANF program in part because they had so much discretion over the funds to begin with. Doing so was easy. Up until the Clinton administration, welfare was a cash entitlement. To sign up, families needed to meet relatively straightforward standards; anyone who qualified got the cash from the government. Then—motivated in no small part by racist concerns about Black mothers abusing the program, typified by the mythic welfare queen—Republicans and Democrats joined together in 1996 to get rid of the entitlement and replace it with a block grant. Uncle Sam would give each state a pool of cash to spend on programs for very poor kids and families, as they saw fit.

Some states kept a robust cash-assistance program. Others, including Mississippi, diverted the money to education, child care, and workforce development—and, in Mississippi’s case, to more esoteric policy priorities including marriage promotion and leadership training. Federal and state oversight was loose, and money flowed to programs that were ineffective or even outright shams. “How is it that money that is supposed to be targeted to struggling families is being siphoned off for political patronage?” Oleta Fitzgerald, the director of the southern regional office of the Children’s Defense Fund, told me in a recent interview. “Block-granting gives you the ability to misspend money, and do contracts with your friends and family, and do stupid contracts for things that you want.”

Zach Parolin: Welfare money is paying for a lot of things besides welfare

In Mississippi’s case, the state misspent millions: roughly $80 million from 2016 to 2020, and perhaps much more, according to a forensic audit commissioned by the state after the scandal broke. Even now, it continues to fritter away taxpayer dollars, using $30 million a year in TANF money to fill budget holes; disbursing $35 million a year to vendors and nonprofits, many without reliable track records of helping anyone; and letting $20 million go unused. Remarkably, the program does next to nothing to end poverty, experts think. According to the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, only 4 percent of poor Mississippians received cash benefits. “I don’t know any family who has gotten TANF in the past five years,” Aisha Nyandoro, who runs the Jackson-based nonprofit Springboard to Opportunities, told me. Indeed, the state typically rejects more than 90 percent of applicants, and in some years more than 98 percent.

Both Nyandoro and Fitzgerald noted the irony that the state treated the poor people who applied for TANF as if they were the ones defrauding the taxpayers: The program was not just stingy, but onerous and invasive for applicants. “If someone provided information on their income level that was $100 off” or “misunderstood the rules or the paperwork,” they might be threatened with sanctions or kicked out of the program, Fitzgerald told me.

Some state and nonprofit officials involved in the scandal have pleaded guilty to criminal charges. But what was legal and permissible for TANF in Mississippi is just as scandalous. The whole program nationwide should be understood as an outrage: Mississippi is offering just the most extreme outgrowth of a punitive, racist, stingy, poorly designed, and ineffective system, one that fails the children it purports to help.

For one, TANF is too small to accomplish its goal of getting kids out of poverty. The federal government’s total disbursement to states is stuck at its 1996 level—with no budgetary changes to account for the growth of the population, the ravages of recessions, or even inflation. An initiative that once aided the majority of poor families now aids just a sliver of them: 437,000 adults and 1.6 million kids nationwide as of 2019, a year in which 23 million adults and 11 million children were living in poverty. (The American Rescue Plan, President Joe Biden’s COVID-response package, included some new TANF funding, but just $1 billion of it and on a temporary basis.)

After the 1996 reforms, the whole program “was regulated by tougher rules and requirements, and stronger modes of surveillance and punishment,” the University of Minnesota sociologist Joe Soss told me. “You see these programs reconstructed to focus on reforming the individual, enforcing work, promoting heterosexual marriage, and encouraging ‘self-discipline.’ These developments have all been significantly more pronounced in states where Black people make up a higher percentage of the population.” Moreover, the program is too lax in terms of oversight. In many states, TANF money has become a slush fund.

Annie Lowrey: Is this the end of welfare as we know it?

Many good proposals would reform TANF to steer more cash benefits to poor kids and help usher at-risk young parents into the workforce. Perhaps the best option? Just getting rid of it and using its $16.5 billion a year to help bring back the beefed-up child tax credit payments that Congress let expire. Those no-strings-attached transfers—which were available to every low- and middle-income American with a dependent under 18 and were disbursed in monthly increments—slashed child poverty in half, after all, and were beloved by the parents of the 61 million children who got them. “It was drastically different,” Nyandoro told me. “There was no bureaucracy. It was run by the federal government, not the state. You knew when the check was coming. And we saw immediately how the child tax credit payments gave families the economic breathing room that they needed, cutting child poverty in half in six months. Why do we keep using [the TANF] system when we have the proof of a system that actually does work?”

The best way to help families would be more like social insurance than a “safety net”—a concept popularized in the 1980s, when Ronald Reagan was shrinking the New Deal and Great Society programs. “The idea of those [older] programs is that we’re socializing risk, and that everybody is at risk of getting ill and getting old and maybe we should have something there to support you that we’ve constructed together,” Soss told me, contrasting Social Security and unemployment insurance with “stingier and stigmatized” programs such as TANF and food stamps.

Mississippi shows the limits of a system grounded not in solidarity with recipients but in contempt for them. The U.S. should end that version of welfare and start again.

$= dv.el('center', 'Source: ' + dv.current().Link + ', ' + dv.current().Date.toLocaleString("fr-FR"))