41 KiB

| Tag | Date | DocType | Hierarchy | TimeStamp | Link | location | CollapseMetaTable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2022-07-17 | WebClipping | 2022-07-17 | https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/The-List-abortions-before-Roe-17291284.php | true |

Parent:: @News Read:: 2022-07-23

name Save

type command

action Save current file

id Save

^button-ItwasasecretroadmaptogetanabortionNSave

It was a secret road map for breaking the law to get an abortion. Now, ‘The List’ and its tactics are resurfacing

- She flew to San Francisco in June 1968 to meet a friend who knew someone who knew someone. Karen L. was 24 and eight weeks pregnant, arriving from Los Angeles. The woman picked her up at San Francisco International and carefully explained what to do next. There was a phone number; there was a code phrase. From the friend’s apartment, Karen dialed the number and spoke the phrase:

A female voice greeted her.

Karen was determined to end her pregnancy. A fifth-grade teacher with red hair and an allergy to birth-control pills, she had been practicing the rhythm method of contraception with her boyfriend, Erwin, who had studied to be a dentist. Though he’d offered to marry her when they found out she was pregnant, Karen did not believe in “shotgun marriages,” as she told him, and she did not want a child right then. She wasn’t ready, mentally or financially. She had grown up in a liberal Jewish family that believed abortion was an individual’s choice, in line with Jewish law and tradition.

But this was five years before Roe v. Wade held that the Constitution protects the right to choose abortion. The procedure was banned or heavily restricted in most states, including California. Typically, according to the legal system, a person seeking an abortion, a person like Karen, was a person plotting a crime.

On the phone at her friend’s apartment, Karen was afraid to give her name, and the voice on the other end did not ask for it. The woman simply gave her an address — 30 Clement St. — and a set of instructions: Ring the bell four times. Mention “Patricia Maginnis.” Then proceed to the second floor.

Karen and her friend soon found themselves at a Victorian house divided into apartments in San Francisco’s Inner Richmond neighborhood. Up a steep flight of stairs, the landing gave way to polished wood floors and a living room and dining room that contained little else but tables and some bookshelves. They saw piles of literature and some women quietly stuffing envelopes with papers.

The women told the two L.A. visitors to join them. Karen didn’t look too closely at the literature, only noticing that it mentioned political efforts to make abortion legal. After two hours, a woman beckoned Karen into a smaller room, telling the friend to stay behind.

The woman gestured toward a set of photocopies in neat stacks, numbered pages of a single long document. This was the “Specialist Listing,” or simply “the List.” It contained the names and phone numbers of dozens of abortion providers in Mexico and Japan, along with tips about selecting a provider in those countries, preparing for the surgery and — if necessary — dodging the police.

It was a road map for breaking the law to get a safe abortion.

Now Playing:

In 1968, at 24 years old, Karen L. needed an abortion, which was illegal in the U.S. She relied on an underground network of activists in San Francisco to obtain the surgery. Video: Reshma Kirpalani Special to The Chronicle

- “No law can stop a woman,” Karen L. recently told The Chronicle, which is identifying her by first name and last initial, as she requested for privacy and safety reasons. “I was going to risk my life,” she said. “But I was still going to do it.”

The day 54 years ago when she visited the apartment on Clement Street and read the List, she realized she could be thrown in prison, or worse. She carefully folded a few pages of the List into an envelope, left the activists’ apartment, flew back to L.A. and began planning a trip to Mexico.

Polls show that a majority of Americans think abortion should be legal in all or most cases. More than two dozen leading medical associations say abortion is a safe and essential part of health care. But the GOP-appointed majority on the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe last month, calling the precedent “egregiously wrong from the start” and claiming the Constitution does not protect the right to abortion. Chief Justice John Roberts wrote separately that he would not go as far, upholding an Mississippi abortion ban while calling the majority’s decision an “unnecessary” and “dramatic” one that guts Roe “down to the studs.”

The decision paves the way for states or the federal government to ban abortion. Eight states have now made it illegal in all or most cases, with more states moving to pass bans. Some Republican Party officials are going further, crafting state laws to stop patients from traveling to other states for abortion care. In the meantime, Democratic Party leaders like Gov. Gavin Newsom say they’ll defend abortion access and offer sanctuary. On Friday, President Biden signed an executive order that takes small steps to protect some abortion patients and providers.

Years of scientific studies show that restrictive laws don’t stop abortions, but drive them underground instead. Women will still get abortions, and so will transgender and nonbinary people, who face additional barriers and stigmas. Abortion-rights advocates are telling people on social media to delete their period trackers and start using secure-messaging apps. Some activists are already preparing patients to evade surveillance and break the law to get care.

In other words, they’re doing what the List’s architects were doing more than half a century ago.

Created in San Francisco by a former U.S. Army nurse named Patricia Maginnis, the List was merely the visible component of a well-organized and efficient clandestine network that sprawled across multiple countries and incorporated the wisdom of thousands. It guided about 12,000 people to safe abortions before Roe, evolving into one of the biggest feminist projects in the country — comparable in scope to Jane, a similar group in Chicago and the subject of a recent HBO documentary.

But the List is not as well known today. Even Maginnis, who died last summer at 93, is hardly a household name, despite the fact that her radical approach transformed the abortion debate and inspired the creation of NARAL Pro-Choice America, the prominent national advocacy group. “She deserves to be much more famous than she is,” said Lili Loofbourow, an Oakland-based staff writer for Slate who profiled Maginnis in 2018. “The debate still has not caught up to where she was.”

The Chronicle recently spent three days at the Schlesinger Library in Massachusetts, part of the Harvard Radcliffe Institute, examining hundreds of manila folders full of files that Maginnis donated. These are records from the two groups she co-founded in the mid-1960s: the Society for Humane Abortion, or SHA, which published educational materials and sponsored public talks about the need for safe abortions, and the Association to Repeal Abortion Laws, or ARAL, which dealt in underground activities and maintained the List.

The records document every aspect of the List’s creation and upkeep. They are both meticulously detailed and secretive, marked everywhere with code numbers that ARAL employed to preserve the privacy of doctors and patients in an era when police and prosecutors sought to expose them.

While many of these files have been available since the late 1970s, some were sitting in Maginnis’ East Oakland home until 2017. These particular folders have received little attention.

They are full of letters that women and their loved ones wrote to her, begging for help.

Some are neatly typed, others handwritten on pink or purple or white or yellow paper. Drawings of flowers peek out from the edges of custom stationery. Almost all are redacted, with names and addresses blacked out or excised with scissors. They vary in length from an index card (“I NEED HELP!!”) to an eight-page missive written “in the middle of the nite (sic).” The postmarks are from every corner of California and all over the country: Michigan, New York, Florida, Ohio, Alaska.

The common thread is a tone of urgency, often bordering on desperation:

“Since I am 6 weeks pregnant, every day is quite important to me, so please act accordingly.” (woman in Elgin, Ill.)

“I have almost reached the state of panic.” (college student, L.A.)

“This is an S.O.S. letter.” (27-year-old divorcee, San Francisco)

“I can’t have it, but don’t want to kill myself. The boys need me. But I’m going crazy trying to figure a way out.” (44-year-old widow and mother of three sons, Florida)

There are hundreds and hundreds of these letters.

As might be expected, many of them concern young women who, like Karen L., had never been pregnant before. High school students, college students, office workers. They told Maginnis they wanted to finish school; they were broke or in debt; they couldn’t afford a kid; they just weren’t ready.

However, a substantial number of letter-writers said they were already mothers, raising children in stable marriages or as divorcees. The Supreme Court had affirmed the legal right to contraception only in 1965, and it was still not widely available. Wives shared stories of failed IUDs and adverse reactions to birth-control pills. “I wish you every success in your crusade against our present laws,” wrote a Long Beach woman in January 1968, signing the letter with her husband’s name and a “Mrs.” in front. “Women like myself who are married and cannot take the ‘Pill’ for medical reasons are really trapped.”

Strikingly, the medical establishment offered little comfort to women in that era. Over and over in letters to ARAL, women said they had already asked their usual doctors for help but had been turned down. “Our family doctor … told us he was sorry, understood our plight, but could not help,” wrote a mother of five in Westminster (Orange County) in early 1967.

Doctors found themselves in positions they found nearly impossible. Philip Darney, a longtime obstetrician at San Francisco General Hospital, was a UCSF medical student training there in the late 1960s. “We didn’t learn anything about abortion in medical school,” he recalled in an interview. But his teachers spoke about being haunted by “the carnage” that resulted from botched abortions and people who tried to end their pregnancies themselves: wreckage to internal organs, gory infections. A California public health official estimated in 1962 that between 18,000 and 108,000 illegal abortions were performed annually in the state. In 1965, there were about 200 deaths in the U.S. from such surgeries.

Sometimes individual doctors did flout the law in private, performing abortions for longtime patients — Darney said the medical students heard occasional “whispers” of abortions at S.F. General — but it was a huge professional risk. Physicians could be prosecuted, their patients interrogated and dragged into court. In 1966, after nine UCSF gynecologists performed abortions for women infected with rubella, which could cause severe birth defects, the state medical board accused them of “professional misconduct” and threatened to pull their licenses.

Starting in late 1967, California law changed to allow abortions to be performed in a hospital, but only in severely limited cases and subject to approval by male-dominated hospital boards. Such restrictions continued to drive patients toward illegal providers, despite the notorious medical risks.

And there were all kinds of scary outcomes of illegal abortions that fell short of long-term injury or death. In 1968, 15-year-old Wendy Winston of Los Angeles learned she was pregnant by her high school boyfriend. Her family hired a nurse practitioner to perform an at-home abortion when she was about three months along, Winston said.

Wendy Winston at home near Los Angeles. She got pregnant at age 15, and had a frightening experience with an at-home illegal abortion.

Brontë Wittpenn/The Chronicle

The teenager was overwhelmed; the nurse, who seemed anxious, explained little. Winston remembers that the nurse inserted a plastic tube into her vagina, which soon caused contractions and lots of bleeding, which the nurse tried to slow with gauze. She gave Winston thick period pads to put in her underwear, then left the home. Winston bled through the night with her mother at her side. The next morning, she felt the fetus pass.

Without an abortion, “I wouldn’t have been able to finish high school, since both my mom and my dad worked and my grandmother was too old to take care of a baby,” Winston, who is now 69 and still lives in the L.A. area, recently told The Chronicle. But at the time, she found the experience terrifying.

Pls combo caption here: A 1990s photo of then 43-year-old Wendy Winston after she graduated college at Loyola Marymount University can be seen in her home in Venice, Calif. on Wednesday, June 29, 2022. When Winston was 15 she became pregnant while dating her high school boyfriend. When a doctor said he couldn’t perform an abortion, Winston’s mother, Patricia, hand-wrote a letter to an underground, feminist healthcare network that existed in the 60s that helped women and their families get connected to providers to obtain abortions. The organization, Society for Human Abortion, was able to connect Winston with a nurse who performed the abortion at her home. After the abortion and two decades later Winston went on to have two daughters of her own, graduated college as a single mother and ran several businesses.

Provided by Wendy Winston / Provided by Wendy Winston

A photo of Wendy Winston’s mother Patricia Anne Luer with her grandchild and Wendy’s daughter Analisa Curzi in 1994. Provided by Wendy Winston

Left: Wendy Winston in a photo taken when she graduated from Loyola Marymount University at age 43 in the 1990s. Right: Winston’s mother, Patricia Anne Luer, with her grandchild, Winston’s daughter Analisa Curzi, in 1994. Photos provided by Wendy Winston Top: Wendy Winston in a photo taken when she graduated from Loyola Marymount University at age 43 in the 1990s. Above: Winston’s mother, Patricia Anne Luer, with her grandchild, Winston’s daughter Analisa Curzi, in 1994. Photos provided by Wendy Winston

Foreign abortions introduced yet more unknowns. While the rich could get care in countries where abortion was legal, like Japan, many people could only afford a trip to Mexico. The procedure, banned there, was widely available through illegal providers, but few patients knew how to navigate the Mexican abortion landscape. For instance, Winston’s mother, Patti, had initially considered taking her across the border for an abortion but decided against it, as she explained in a letter to ARAL in September 1968. “I hate to do that for fear of falling into the hands of someone who is not a reputable doctor,” Patti wrote.

Now Playing:

Wendy Winston said that her mother, Patricia, hand-wrote a letter to an underground, feminist healthcare network that existed in the 60s that helped women and their families get connected to providers to obtain abortions. Video: Bronte Wittpenn The Chronicle

Patients during those years were so demoralized by the lack of safe options that many told ARAL they wanted to kill themselves. “Please I’m so scared I don’t know what to do,” a young woman in Daly City typed in April 1968. “Sometimes I think it would solve everything if I were dead.” Men often reported that wives and girlfriends were uttering disturbing comments. “I am afraid for her welfare,” a 20-year-old UC Santa Barbara student wrote that year. “She would kill herself rather than tell her parents.”

Some of the most desperate situations involved rape. Multiple letters in the ARAL archive mention rape victims who had been too afraid to tell police and were now carrying their rapist’s baby. In 1968, a Chicago man told Maginnis about the recent rape of his fiancee. “She was to (sic) terrified to tell anyone, including myself,” he wrote. “When her period did not materialize when it should have, she broke down and told me the entire story.”

Regardless of age or circumstance, most everyone writing to San Francisco asked for the same thing: Names of competent abortion providers. They wanted a copy of the List.

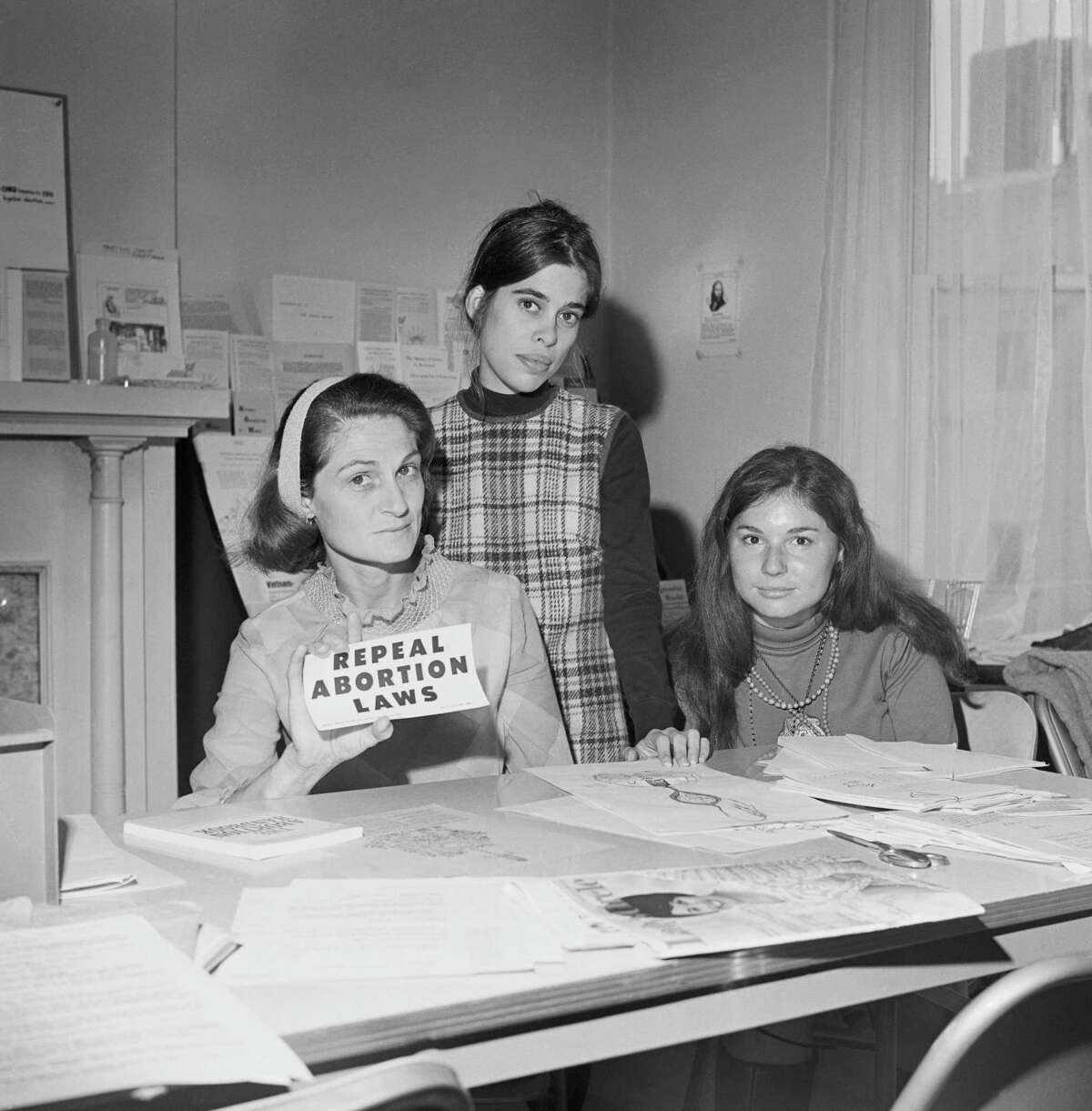

Patricia Maginnis at a 1971 Women’s Abortion Action Coalition conference and demonstration.

Bob O’Connor / Special to The Chronicle 1971

- The List began with an act of civil disobedience. On June 16, 1966, Patricia Maginnis carried a shopping bag full of yellow leaflets into the Financial District. A slender woman of 38 in an overcoat and dark pumps, she spent the day handing the sheets to passersby in front of office buildings, as well as at the Federal Building and UCSF, where the state medical board was meeting.

“At the entrance to the campus,” a Chronicle reporter noted at the time, “she gave a leaflet to a priest, who returned a few minutes later and gave it back.”

“ARE YOU PREGNANT?” one of the leaflets read. “IS YOURS A WANTED PREGNANCY? IF NOT, WHY NOT SEE AN ABORTIONIST.” It went on to give the names and contact information of 10 abortion providers in Mexico, one in Japan and a clinic in Sweden.

It was the first draft of the List.

Maginnis actually hoped the act of circulating it would get her arrested. California law at the time forbade “soliciting” an abortion or “providing and supplying” the means for procuring one — felonies punishable by up to five years in prison. She wanted to challenge the law in court, which could only happen if she were first handcuffed and charged. But no police intervened that day, likely fearing the very publicity she was trying to spur: Maginnis was fast becoming one of the most influential abortion-rights activists in America.

Raised in a strict Catholic home in Oklahoma, she’d been radicalized by her experiences as an Army nurse in the 1950s, stationed at bases in Panama and the U.S. and caring for women in obstetrics wards. She saw a lot of forced birth there — women made to deliver babies they had already tried and failed to abort by their own hands, or non-viable babies with severe birth defects. Once she saw doctors place a wire cage over the bed of a screaming woman during a delivery, “as if she were an animal,” Maginnis later told a reporter for Los Angeles FM & Fine Arts magazine.

It wasn’t enough to relax or “reform” abortion laws, she felt; they all just had to go. After leaving the Army and moving to San Francisco, Maginnis met two friends who felt the same — Rowena Gurner, a Palo Alto electronics designer, and Lana Phelan, a Long Beach legal assistant — and they formed SHA and ARAL to spread the message. “We regard abortion as a simple surgical procedure and not a criminal offense,” SHA literature declared: Abortion was medicine, and it should be available to anyone, at any time, without apology, ideally for free.

“She’s really the first one who starts to write that way: The laws are wrong,” said Leslie Reagan, professor of history at the University of Illinois, who has studied ARAL and wrote the book “When Abortion Was a Crime.” “She’s not afraid of what anyone thinks of her.”

Their entire budget for 1966 was less than $10,000, supplemented by whatever Maginnis earned from working weekend shifts at a hospital lab. Their headquarters was her walk-up apartment in the Richmond. “She said, ‘We’re going to do this with Scotch tape and Xeroxes, and pick up clothes off the street and wear them,’” said Loofbourow, the Slate writer.

That intensity drew people to Maginnis. She worked with Black organizers in San Francisco to advocate legalization and printed leaflets in Spanish. Along with Gurner and Phelan, she taught abortion classes in the Bay Area and on trips to the Midwest. The classes usually began with an overview of female reproductive anatomy, then reviewed various abortion techniques, including surgical procedures such as dilation and curettage (D&C ) and a do-it-yourself technique that involved direct manipulation of the uterus with a finger or a saline wash.

Most patients, she stressed, would be better off with a D&C. It was several times safer than childbirth if performed by a professional, and by the mid-1960s, abortionists in Mexico were doing D&Cs with modern suction equipment. “So please won’t you go to Mexico if you possibly can?” Maginnis implored a group of Palo Alto women who gathered to hear her speak in 1967.

ARAL believed that despite its considerable risks, Mexico was the best option for many patients. Though Mexican police did routinely arrest or harass abortion providers, they had no power to chase anyone back into the U.S., which gave visitors some protection. And it was close, of course, which reduced the time and expense of the journey: A woman in California, Arizona, New Mexico or Texas could cross the border in the morning and be home that night.

After June 1966, when Maginnis put abortionists’ names on leaflets as a form of protest and California media covered it, demand for the information grew quickly. Soon Maginnis was answering 75 phone calls a week at Clement Street, dozens of letters arrived each month requesting copies of the List, and patients and their partners began streaming across the border into Mexico, seeking out the highlighted abortion providers.

Naturally, the activists felt responsible for the safety of those patients, so the women of ARAL began to formalize and expand the List, building a system to ensure its accuracy. The system depended on a number of checks and balances, including in-person tours of the clinics by ARAL volunteers, exchanges of letters with the doctors and a paper-and-pencil form of crowdsourcing. Altogether, it amounted to nothing less than “the first open (and illegal) abortion referral service in the United States,” Leslie Reagan wrote in a 2000 historical study of ARAL.

Jane, the abortion underground based in Chicago, also helped women get illegal abortions, but the bulk of their work was training activists to perform secret abortions themselves, instead of pointing people to medical specialists abroad. The List was more like an “underground feminist health agency,” in Reagan’s description: Within a year or two of the first draft, by summer 1968, a couple of women on Clement Street were basically running an international public health department.

4. In the third week of June 1968, Karen L. packed a Spanish-English dictionary, an oral thermometer, sanitary napkins and “sturdy walking shoes,” as the List advised. A “neat, conservative appearance will make you inconspicuous. If questioned, say you are a tourist.”

She picked Ciudad Juarez, a short taxi ride from the Texas border. It seemed as good a place as any. The first several doctors on the List were all located there, and a few seemed to have positive reviews. On a scrap of paper, she wrote down the phone numbers of the three most promising specialists. One was “a busy family doctor.” Another ran a “large sanitorium” that provided care ranging from “unbelievably excellent to poor.” A third was a highly praised female provider.

In an excess of caution, before getting on the plane to El Paso, where she and her boyfriend would cross the border, Karen scribbled a fourth number, of a male doctor whose description was shorter, with few reviews. She tucked the paper in her bag, leaving the List pages at home.

A few days later, she and Erwin arrived in El Paso.

At a bar pay phone, she unfolded the scrap of paper and plunked in some change. She began to sweat as, one after another, the voices on the other end told her the same thing in halting English or in Spanish, which Karen spoke: They could not help her right now. The first doctor “had to leave to take care of a sick family member”; the second number had been disconnected; the third doctor was not taking patients for two weeks. Please call back then, or in a month.

Panicked now, and feeling weak in the knees, she looked again at the crumpled sheet. The only number she hadn’t tried was for the doctor with the most minimal entry on the List.

Dial tone.

Karen punched in the fourth and last number.

“Patricia Maginnis sent me,” she said.

“Yes,” a woman answered, “I’ll get the doctor.” Moments later, a man greeted her in smooth English and told her exactly what to do next.

A leader in the movement for unrestricted abortion, Patricia Maginnis stands next to a bulletin board full of abortion information in Sausalito, Calif. in the 1960s.

Bettmann Archive / Getty Images

5. The abortionists on the List were an eclectic mix. Most, but not all, were licensed physicians. ARAL referred to them broadly as “specialists” and kept a detailed file on each, keyed to a code number.

According to the files, No. 26, a Tokyo doctor, was “a stocky, kind-faced man with very sure hands.” No. 39 was a middle-aged Spaniard with an anxious demeanor and a clean Mexicali clinic two blocks from the U.S. border. No. 8, in San Luis Rio Colorado near Yuma, Ariz., stocked the antibiotic Terramycin and was “highly recommended.” No. 43, in Juarez, “may act as if he doesn’t speak or understand English. Don’t believe it.”

Maginnis brokered informal deals with the specialists. She promised to direct patients to their clinics and avoid exposing the most sensitive details about their practices to law enforcement. In exchange, the specialists agreed to treat the referred patients kindly and charge a reasonable fee. The price of an illegal abortion in Mexico, always paid in cash, ranged widely, from $150 to $700 U.S. ($1,250 to $6,000 in today’s dollars). Cost depended on the provider, the size of his staff and his ethics; Maginnis often haggled the providers down and even negotiated free abortions for patients who could not afford them.

ARAL insisted, too, that providers allow inspections of their facilities. The author Susan Berman visited an abortion clinic in San Luis in 1970 on ARAL’s behalf, filing a colorful dispatch to Clement Street:

More on Roe v. Wade Overturned

The clinic was in a brand new tract type house on the outskirts of San Luis. … The operating room had a table with a clean piece of paper over it, stirrups and a leather cut out for the ass. … The clinic had no thermometers, nor blood pressure taker. Dr. (redacted) said they were probably there but he couldn’t find them. ... Dr. (redacted) said he had been to a private high school in Ohio and to the University of Mexico Medical School. I asked to see his credential but he said he didn’t bring them in case he was busted.

At times, ARAL’s files read more like the records of a democratic resistance movement than a health bureaucracy. Police surveillance was a constant threat, particularly on the Mexico side, requiring the activists and doctors to switch phone numbers, speak through intermediaries and mail each other from hotels. There were times when police pressure forced specialists to lie low for months; their nurses would tell patients the doctor was “on vacation.”

Occasionally, ARAL received allegations that a specialist had committed fraud or misconduct, requiring them to scratch a name from the List or append a warning. For example, in October 1967, an 18-year-old college freshman from Palo Alto told Maginnis in a letter that a male provider in Agua Prieta had botched her abortion, damaged her uterus and then tried to rape her. After interviewing the traumatized woman, Gurner wrote to the doctor directly.

“Words will not describe how horrified we feel,” she said, demanding that he refund the girl’s $300. “We shall have to warn people who contact us about your unprofessional conduct.” Gurner photocopied the letter, marked it with the specialist’s code (No. 53), and tucked it in his permanent file.

Crucially, the activists included a survey form with each copy of the List, asking patients to fill it out and send it back after their surgeries, “for the sake of the next woman,” as Phelan put it once. These accounts, many of which are preserved at the Schlesinger Library, allowed ARAL to incorporate feedback in close to real time.

“The operation was carried-out in the strictest hospital way,” a 29-year-old San Francisco woman wrote to Maginnis in 1966 about a San Luis abortion. “I was swabbed liberally with antiseptic liquid — pink — and shaven naked as a babe!!!” The boyfriend of one patient reported that “the whole thing took 20 minutes” in a “spotless” Nogales clinic where “an old mamasita (sic) type” tended to his partner after the procedure.

Many patients were so pleased with the care in Mexico that they mailed long narrative accounts of their abortions to Maginnis in addition to filling out the standard ARAL survey. A common theme in these letters is surprise — at how easy it all could be.

“The whole experience was completely rewarding and not at all terrifying in any respect to any of us,” wrote a woman who traveled to a Juarez clinic with three other patients in 1967. One woman who went to Nogales for an abortion marveled, “It’s such a simple procedure the most difficult thing is the expense and breaking the law!” Another wrote, “I had my abortion and lived happily ever after.”

The more people used the List, fact-checking it as they went, the more reliable it became. A new version was printed most every month, with “Supplements” issued in between on a near-daily basis. Swelling from the original one-page flyer to eight pages to 20, the List ebbed and flowed with the experiences of women and the struggles of providers as they all tried to live their lives and stay out of jail.

As well as this system worked most of the time, the fact that it worked at all was a minor miracle, requiring significant effort, luck and trust. Patients relying on the List needed to know that ARAL and the specialists would keep their secret. And there were massive risks inherent to an abortion referral service that ARAL lacked the power to eliminate. All they could do was be as blunt as possible:

WARNING. ABORTION IS ILLEGAL IN MEXICO. DO NOT CARRY THIS LIST INTO MEXICO. The ARAL cannot guarantee refunds in cases of incomplete abortions, nor can we guarantee bail funds in case of arrest …

In 1968, at 24 years old, Karen L. needed an abortion. She traveled to Ciudad Juarez to obtain one.

Reshma Kirpalani/Special to The Chronicle

6. The morning of Karen’s appointment in Juarez, she and Erwin followed the instructions given over the phone by the doctor. They took a taxi to a fountain in the city’s downtown. Waiting for them there was a handsome, dark-haired man in his 30s: Specialist No. 55. The couple hugged him, pretending they were all old friends. The Americans climbed into his silver car.

According to ARAL’s archives, No. 55 was a bit of a mystery at that point. He first appeared on the List in 1967. For unclear reasons, his name had been crossed out in early 1968, months before Karen met him in Juarez. “We do not know if he is a physician,” ARAL had written, and, worse, “We do not trust him.” But then the group toured one of his offices and confirmed his medical credentials — he was an M.D. who had trained at St. Luke’s Hospital in Massachusetts as well as a Juarez hospital — and he was re-added to the List by the time Karen picked up her photocopies at Clement Street.

Departing from the city’s fountain, No. 55 drove Karen and her boyfriend through the streets of Juarez, doubling back a few times, before stopping in an alley next to the back door of a building.

Here it is, the proverbial back alley, Karen remembers thinking. But then the doctor ushered her inside, where she saw “a small, spotless office with two rooms, one for the procedure and one for recovery,” she wrote a few months later in an essay about her abortion. “Instruments were laid out on a shelf behind glass cabinet doors. ... A nurse or assistant greeted us, I changed into a gown, and that’s all I remember before the anesthesia put me out.”

She awoke feeling fine, other than some grogginess and slight discomfort. An hour later, she dressed and left with Erwin, who took her back to the hotel. Later that evening the couple went to dinner with the doctor at Martino’s, a Juarez restaurant popular with tourists and featuring a menu of French and Spanish specialties.

The next day, Karen threw the crumpled slip of paper with the providers’ names into a trash can and crossed back into the U.S. feeling “huge relief,” she recalled. “I was alive.”

An appointment with her L.A. gynecologist a few days later confirmed that she was healthy and the Mexican doctor had done a “good job,” the obstetrician told her. Karen moved on with her life. “I had no regrets of any kind,” she recently said. “I just felt lucky.”

Soon after the surgery, Karen remembered her duty to update the List and wrote Maginnis an eight-page letter, a copy of which exists at the Schlesinger Library. Though it contains no name or address — it is signed “A Grateful Soul” — The Chronicle was able to identify Karen’s letter by the date (June 26, 1968) as well as some details, and when emailed a copy, she confirmed it was hers.

“Your list was complete and served as a bible in these past few troubled and desperate weeks,” Karen had written, thanking Maginnis and describing Specialist No. 55 as kind, “very polite” and “extremely capable.”

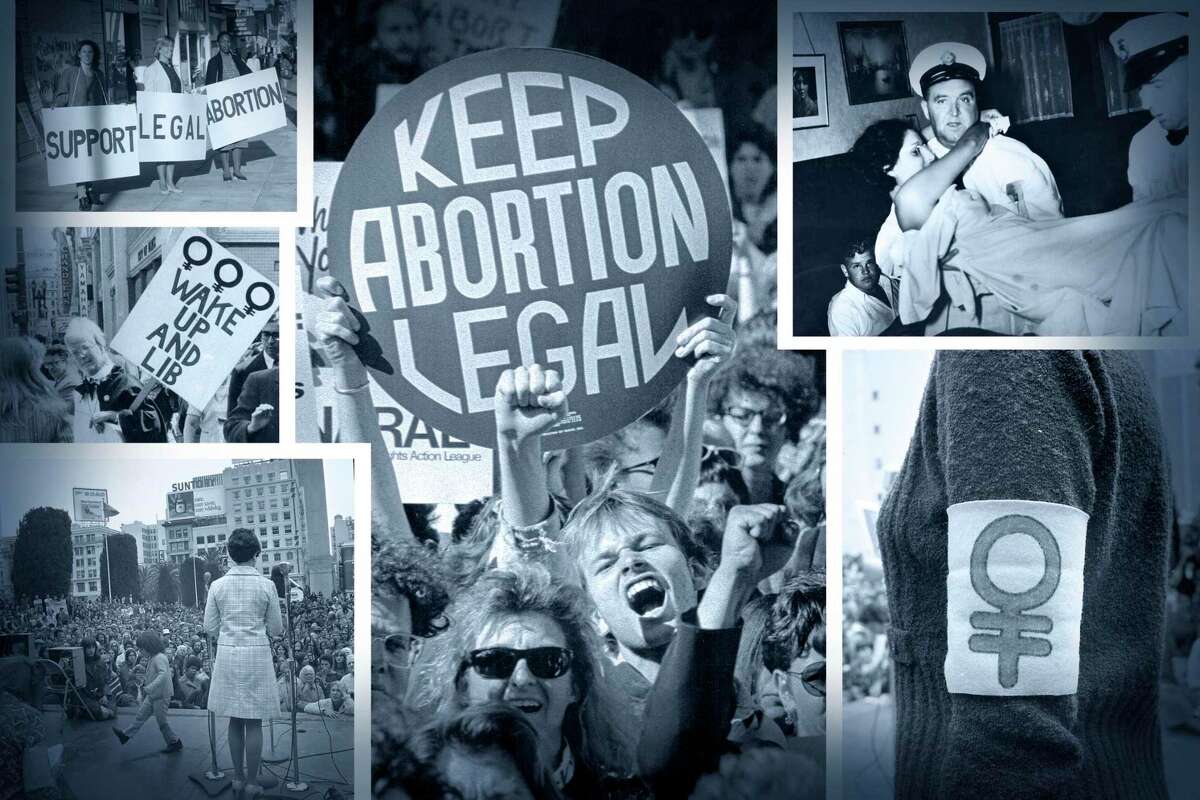

Images from events related to abortion rights, including demonstrations in support of legal abortion and women’s rights in San Francisco in the 1970s and ’80s; and the 1935 removal of a woman (top right) from a San Francisco apartment in which illegal abortions were performed.

Collage by Daymond Gascon / The Chronicle from elements by Bettmann Archive / Getty Images and The Chronicle

7. As the feminist movement gained momentum through the late 1960s, and people kept dying from forced births and botched abortions, public opinion shifted and laws began to change. In 1970, New York legalized abortion up to the 24th week of pregnancy; Roe v. Wade followed in 1973.

American doctors were finally able to perform abortions in the open, and the impact was profound. The first full year after Roe, 1974, at least 900,000 patients received legal abortions in 2,000 U.S. hospitals and clinics. Medical schools began teaching the procedure, and abortion was integrated into medical practice. With safe abortions now available, maternal death rates plummeted, and care kept getting better.

In the 50 years since Roe, “We have improved abortion techniques and learned an immense amount,” said Darney, who became chief of obstetrics at S.F. General. He and his wife, the psychologist Uta Landy, went on to build what is now the Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health at UCSF, which pioneered a multidisciplinary model for sexual health. Today, medical research shows that legal abortion in the U.S. is safe and effective — 14 times safer than childbirth, according to a 2012 study, and safer even than colonoscopies and some dental procedures, according to a comprehensive 2018 review.

Maginnis and her co-founders never claimed that the List was any substitute for a legal and regulated system of professional medicine. As Rowena Gurner wrote in a 1967 letter, “Some day, we hope the cruel abortion laws will be repealed and that women will be able to go to their own physicians for proper abortion care.”

The activists disbanded SHA and ARAL in 1975. But they had achieved something remarkable: Between 1966 and 1970, they had transformed a yellow leaflet into a health service of last resort, helping thousands who had almost nowhere else to turn. Like Karen, who never met Maginnis or gave ARAL her real name, the users of the List were able to preserve their privacy while contributing to an analog database of enormous power, which they used to shape their own fates.

After 1968, Karen left teaching and became a social worker, helping Spanish-speaking families. She wanted to work in the field of family planning; the experience in Mexico had convinced her that the right to choose was fundamental. Over the decades, though, she didn’t really talk about her own abortion. Karen is now in her 70s and runs her own company. And it was only a few months ago, hearing that the Supreme Court was poised to reverse Roe, when she dug out the essay she’d written back in the summer of 1968. It had been sitting in a cabinet all this time. The title was “Odyssey Into the Abortion Underground When it was a Crime.”

Now there will be “undergrounds everywhere,” Karen said. Yes, they’ll be different, relying on digital tools instead of the Postal Service, and they’ll face new challenges: electronic surveillance, aggressive state bans, vigilantes empowered by law to sue patients and anyone assisting them. But, “If you don’t know about the past, you cannot learn from the past,” she said. “This is what we had to go through.”

The List didn’t just change people’s lives by leading them to medical care. It gave them a glimpse of a world that seemed kinder and saner and very much within reach. Over and over, in their post-abortion letters to ARAL, women said their experiences with safe, medical abortions in Mexico had shown them that the United States could easily provide such care. Criminalization was senseless, they said in those letters from the 1960s; it couldn’t possibly last much longer.

Many expressed an earnest desire to support the cause of repeal. They told ARAL that if they couldn’t afford to donate money — several apologized for being broke — they would write letters to Congress, tell friends, tell their stories.

“Am very grateful for such an organization as yours,” a San Francisco woman wrote to the group in 1968, describing a successful surgery in a small, tidy clinic and a comfortable recovery during which the doctor brought her Pepsi and a light Mexican meal on a tray. “The change in abortion laws shall be accepted before long I’m certain. I shall come in and help when I can.”

Jason Fagone (he/him) and Alexandria Bordas (she/they) are San Francisco Chronicle staff writers. Email: jason.fagone@sfchronicle.com, alexandria.bordas@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @jfagone, @CrossingBordas

$= dv.el('center', 'Source: ' + dv.current().Link + ', ' + dv.current().Date.toLocaleString("fr-FR"))