26 KiB

| dg-publish | Alias | Tag | Date | DocType | Hierarchy | TimeStamp | Link | location | CollapseMetaTable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| true |

|

2022-04-03 | WebClipping | 2022-04-03 | https://andreaaliseda.substack.com/p/tortilla-de-harina-a-moon-of-mystery | true |

Parent:: @News Read:: 2022-04-13

name Save

type command

action Save current file

id Save

^button-TortilladeHarinaAMoonofMysteryNSave

Tortilla de Harina: A Moon of Mystery

Photo from prexels.

Writer’s note: Thank you for being here! February was a wash, but I’m back with a dispatch for the month of March. The newsletter is free, though if you wish to support my work––if you’re able and if it calls to you––shoot me a tip via Venmo at @andreaaliseda. Otherwise, relax, enjoy, share with a friend! This one’s a long one, so settle in and get comfortable. Un abrazo!

-

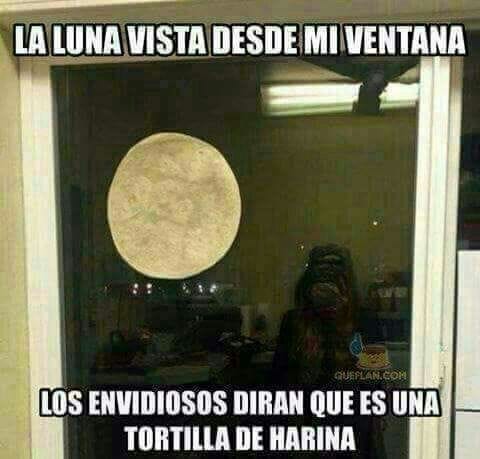

Chewy, translucent, buttery, and soft, the tortilla de harina rises on the comal like a sand-colored moon with charcoal etched craters. And with it, rise 500 years of history and culture that ride along the edges of northern Mexico and its borderlands.

To Norteños, like my partner Marcel, who is from Mexicali, Baja California, tortillas de harina are a religion. So much so that even tacos, like cabeza, tripas, carne asada or al pastor, are famously served on their soft and chewy surface. Yes, tacos, not burritos. As a Tijuanense, in my home, tortillas de harina and maíz both had their place, and were both fervidly enjoyed. But for norteños and desert descendants like Marcel, where wheat easily thrives in its dry arid heat, and maíz does not––tortillas de harina reign above all.

Javier Cabral’s 2021 piece, A Flour Tortilla Map of Los Angeles from Sonoran to Mexicali-Styles supports this pointed distinction. “Ask anyone in Sonora what the proper tortilla for carne asada is, and they will vehemently respond with ‘de harina, a huevo.’ But ask that same question to a Tijuanense and they will be much laxer in their answer,” he writes.

This response alone reveals how regional borderlands are, by agriculture, climate, and the culture that emerged around it.

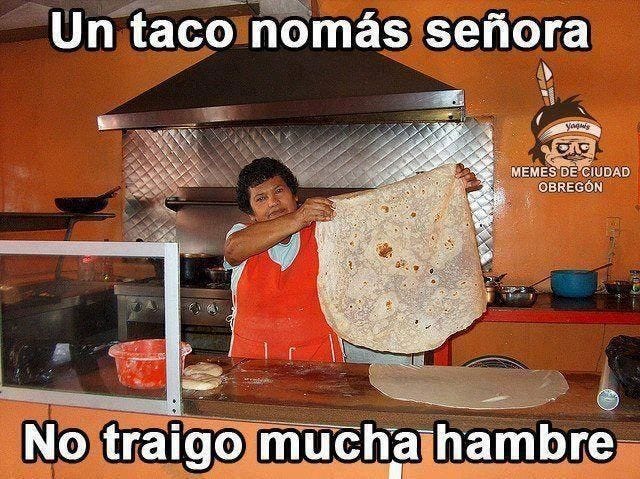

And if Mexicali is known for its tacos with tortilla de harina, then Sonora––which is its neighboring state––is famous for their sobaquera, the pinnacle of the tortilla de harina. Sobaquera translates to “armpitted” as Gustavo Arellano explains in his Splendid Table interview with Francis Lam. Sobaco is slang for armpit, and sobaquera describes a tortilla which is so large and thin that in stretching it, its length reaches the sobaco.

The tortilla de harina has a history that spans over five centuries in the northern borderlands of Mexico, with regional varietals that range in texture and method from the Baja California, Sonora, Sinaloa, Chihuahua, Nuevo Leon regions, where around 45% of Mexico’s wheat production is grown.

So why then, are they still one of the most misunderstood foods in Mexican cuisine?

I suppose, our answer lies in what is perceived by the United States, where what’s most accessible are bleached-looking mass-produced rounds we see in chain grocery stores and fast-food restaurants.

In the Splendid Table interview, Arellano says what I’m thinking when the interviewer echos the USian consumer’s relation of tortillas de harina to Taco Bell and to its many commodified versions. “[People who think this] have never had a good flour tortilla in their life,” Arellano exclaims. Y punto. “I would say most people who know flour tortillas now know the Chipotle model, which is mass-produced,” he explains. But this model, dear reader, is not the flour tortillas I know, nor the ones my partner was shaped with, nor the ones Sonora is revered for. Not the ones you can dab a pat of butter on a freshly warmed round and roll it up as a midday snack. No, señor. These are bastardized reproductions made to sit on shelves far longer than any tortilla should. These soap-tasting disks are merely capitalism at play––not an accurate representation of our culture as northern and borderland peoples.

A flour tortilla is an experience. A chewy and buttery delight, and it is so intrinsic to our northern palates that chef Eric See of Ursula, as I reported for Bklyner in 2020 when he was still under the moniker The Awkward Scone, had his mom help him ship the thick chewy New Mexican tortillas for his famous breakfast burritos from New Mexico to Brooklyn, NY.

However, there is a larger part of this conversation, an elephant that needs be addressed. So often this deeply interwoven food of our border culture is characterized and boiled down to its seed of origin: a product of colonization.

Wheat.

It’s complex.

Soleil Ho touches on this bruise in our culture in their piece, These artisanal flour tortillas are nothing like what you get at a grocery store. Here’s how to find them, when explaining why there exists hesitation in the US. They write, “Artisanal flour tortilla hasn’t taken off in national popularity quite the way that masa has. Tension still exists around its history: Mexico’s wheat came from 17-century Spanish missionaries who enslaved Indigenous people to cultivate wheat fields in a land that they’d stolen.”

This is where it gets tricky. What they say is true, and also, it’s not all there is to the story––the part where it becomes Mexican gastronomy matters too. In Mexico and Mexican history, one soon comes to find that both things exist, and both things are true. The good and the bad hang together in a constant balance.

Gan Chin Lin touches on fraught colonial relationships with wheat eloquently in her recent piece for Wordloaf on bread, specifically, vegan milk bread, and it resonated with me in this context. She writes, “our heritage is the story of how we came to know wheat in the first place, and the exciting dynamic after, of what we did with it.”

Herein is that story of flour tortillas. What my ancestors did with it.

During Hernan Cortés’ crusades, which we all know violently aimed to eradicate the thriving Indigenous culture that pre-existed his arrivals to impose upon a new society that heralded Eurocentric ideals, one of the many ingredients he brought forth was wheat. This had not only a purpose in palate and flavor, but played a religious role as well. In Spanish culture, bread was sacred; the body of Christ. This is much like maíz was sacred to the Indigenous people; source of human life and its physical form.

Voices of Mexico, an UNAM (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) publication, writes in their piece titled, The Arrival of Wheat in Mexico, “it is quite possible that the first crops of wheat came from the shipments of grain found by Cortés.” However, along with Cortés in this excursion was a free African man, born in West Africa, he is said to have gone to Lisbon enslaved and freed as he joined the expedition to the New World in Sevilla, and is known by the name of Juan Garrido. Garrido is the true shepherd of wheat in Mexico. Legend says that while he cleaned rice for the Mexican army, he found three grains of wheat. Garrido planted them on his plot of land, and only one germinated. But it was from the one that 180 grains sprouted, “from which the cereal was propagated throughout Mexican territory.” The magazine writes that by 1524 wheat was in “significant” production.

The propagation was done with stolen labor, as Ho notes.

Arellano gives further context to these times; during the 1500s-1600s the north, where land took easily to growing wheat, was full of “undesirables.” He says this included Jewish, Muslim, and Moorish peoples.

“The reality is no one knows how flour tortillas got started in Mexico,” Arrellano says, “except that it was done in Northern Mexico.”

Image of Northern Mexico regions and states from timeanddate.com.

Quiminet.com writes that the timeline for tortillas de harina began in 1542 in Sonora, where a mixture of “broken” wheat and water is turned into something that came to be known as “zaruki.” Zaruki is also a village in Iran. But could it be a possible clue to the inhabitants of the north and originators of the flour tortilla?

According to Rocio Carvajal, historian, food writer, and host of Pass The Chipotle––a food-centered historical podcast which untangles the history of Mexico through cuisine––there is. “Spaniards had been colonised by Islam and the 700 years of cultural domination left a deep cultural footprint including food traditions,” she writes via email. “A flatbread from the Zaruki region (present-day Iran) was known to them and presumably many Spanish settlers were very familiar with it and reproduced a similar bread using the newly introduced wheat in the Americas.”

Here, the pieces of the puzzle begin to come together, a shape starts to form, and we begin to see a road to our modern flour tortillas.

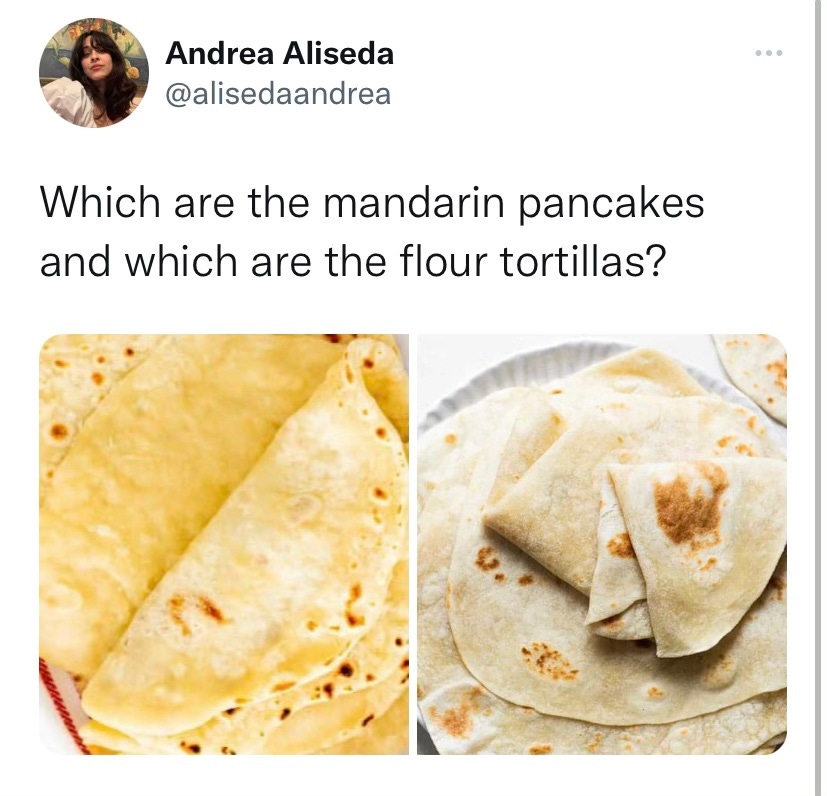

There’s the Iranian influence that Carvajal notes. I think on taftoon bread, round, flat and full of air pockets. I also think of lavash––which Arellano too sees the similarities in flour tortillas––thin, chewy, and slightly bubbly, usually served or sold in long rectangular pieces and baked in a tandoor oven.

Iranian Taftoon bread, usually made with whole wheat flour, milk, eggs, and yogurt. Photo from Taste Atlas.

Then there’s the Arabic influence that is deeply felt in Mexico due to the Spanish conquest. Their imprint is so deep that it’s easily spotted in everyday language. Think: algodón, limón, alcachofa, even, Guadalajara (meaning valley of the stone). Food follows. The Arabic flatbread, known as pita, khubz or kuboos, is also a distinctly clear relative. Linguist and writer David Bowles makes this connection in his Medium piece, ‘Mexican X-plainer: Al-Andalus & the Flour Tortilla’, where he compares a raghīf al-khobz and tortilla de harina ballooning on a comal in identical fashion. Tortillas de harina are Arabic, Bowles writes, like much of our Mexican culture.

This kuboos recipe from Yummy Tummy Aarthi includes flour, sugar, yeast, salt, olive oil, warm water.

When Marcel and I haven’t had access to well-made tortillas de harina––they are resourceful. He will often come back from the store with lavash for quesadillas or burritos, or to be served as sides to dishes. Yet, aside from the textural difference, lavash sometimes differs from flour tortilla in its recipe, calling for sugar, yeast, egg, or yogurt––depending on the recipe’s region of origin. He’s also stocked the fridge with pita, though we don’t always use it as an exact substitute like we have with lavash. But it satisfies their ingrained Mexicali longing for flatbread.

Then there’s roti, what we’d get when living in New York. We’d visit Duals Natural in the East Village and Marcel would grab packs of it to take home––noting how similar roti was to flour tortillas. They were similar in shape, texture, and size to what we were accustomed to in our respective border homelands.

Bowles also touches on the theory of a Jewish influence. “[They] would eat this thin flatbread during ritual times like Passover (when only unleavened bread made of wheat, spelt, barley, rye, or oat is allowed).” he writes. “It IS very similar to unleavened soft matzah (basically kosher tortillas), so I wouldn’t be surprised!”

And just when you think we’ve exhausted all options, and opened every door, I believe there are still stones left unturned. Another possible theory to the tortilla de harina’s origin.

In Marcel’s hometown of Mexicali, there is a big Chinese population and it is known that the Chinese food in Mexicali is king. Though, the truth is, it’s been a very enshrouded history.

Chinese people first came to Mexico in 1564 in what’s considered as the Manila galleons (“ships from China”), according to ‘The Chinos in New Spain: A Corrective Lens for a Distorted Image’ by Edward R. Slack Jr.. “Chino” was the category given to any person of East and South Asian descent, and it created blatant racism and erasure of the peoples who would be brought to Mexico in bondage, who the Spanish depended on for food and other services. Unlike the name suggested, the Chinese were not the only people being brought to Acapulco’s ports in the Manila galleons; Filipino, Japanese and Indian people were also included. The author writes that the Asian “impact on New Spain has been sorely neglected in the histography of colonial Mexico.” Which makes it incredibly difficult to trace which cultures and from what regions of a massive continent, made which contributions in what regions in what came to be the country of Mexico. What we do know, according to the text, is after being freed, Asian peoples of Mexico lived all across the country, some to the states of Baja California in cities like Loreto, and later in Sonora. Which makes me think: if this history is unclear, then dates and places may all be uncertain, and that might mean there’s a possibility for my guess to be as good as any. Even so, 500 years is a long time for the flour tortilla of mysterious origins. I imagine many hands have passed through it, tweaking the recipe and techniques throughout centuries. It could very well be possible for East and South Asian influence to exist in the width of the flour tortilla.

All of this, of course, is just theory.

But, indulge me.

Take for example, this pecking duck pancake recipe, chun bing 春饼 (meaning, spring pancake), from the blog, Red House Spice. The ingredients call for what was once known as “zaruki”: flour and water. The pancakes are translucent and soft. And these Chinese Mandarin pancakes from the blog, China Sichuan Food, which I’d say look nearly identical to the pride of norteño food, boasting the beloved oily sheen and translucent, doughy body. This recipe calls for flour and water as well, with the addition of fat––in this case sesame or vegetable oil. They are had as an accompaniment to stews, dried tofu, moo shu pork and pecking duck, among other things. Much like in Mexican food, they accompany beans, carne asada, seafood, soups, and more. Chinese pancakes have origins in 3rd century Shandong Province and were cooked across copper made griddles to feed soldiers. In the family shared blog, The Woks of Life, Judy writes in the preface of their mandarin pancake recipe, “mandarin pancakes are like the Chinese version of a flour tortilla.” Though I am left wondering; if they predate flour tortillas by roughly 13 centuries, then our flatbreads may actually be the Mexican version of mandarin pancakes.

In its neighboring state, Sonora, mother of the sobaqueras, I question what could be another Asian connection in flour tortillas. Indian influence is felt most notably through Mira or Meera, who was originally said to be from the kingdom of Gran Mogol (Mughal), who would come to be Catarina de San Juan––inspiring much of what we now consider traditional Mexican textiles and garments. But I don’t think it ends there. Look closely at a roti, its recipe also calls for flour, water, and fat, in their case, ghee in lieu of pork fat. But look closer. The rumali roti is paper thin, as Arellano describes for the sobaqueras, stretched out and giant. I found a YouTube video of a man making rumali roti in India, and a woman making sobaqueras in Sonora. Play them side by side––the similarities are striking. Firstly, they both use a rounded comal griddle that sticks out like the belly of the sun. The dough gets rolled with a pin, then using their forearms both the cooks flap it around artfully, in a practiced and memorized quick spinning motion that stretches their dough––all the way to the sobaco. As if rehearsed, they follow the same steps almost to a tee.

Sobaquera

Rumali, or roomali, comes from “roomal” a Hindi word which means handkerchief, according to Times of India. Its history reveals the name is due to its thinness and likeness to a handkerchief, used to sop up oils and cradle meats. It originated in the Mughal era, which started in the 1520s, and is said to have been popular in Punjab, where it is called Lamboo roti, and in its neighboring country, Pakistan as well––where preparation methods are also starkly similar, sans round comal.

If we continue to pull the thread, we see the origins of roti take us back to the origins of flatbread. First Law Comic writes of a Persian origin, “In 500 B.C., records exist that indicate that Persian soldiers baked a flatbread on their shields which they then covered with cheese and dates.” This takes my mind back to “zaruki,” a Persian word which thanks to a friend’s investigation (thanks, Sep and Sep’s dad!), we find it has several translations in Farsi: including yelling in pain from a bee sting or snake bite. “And in some part of Kerman, the province Zaruki is in,” writes Sep (whose dad is fluent in Farsi) via text, “it is a name of a type of bee.” Bee stings cause hot swollen bumps, much like the hot air bubbles that form in a tortilla. Could there be a correlation?

The truth is, I don’t have an answer, Mexican history has many gaping holes and with it, many origins. And even in seeking answers, I too am probably leaving behind holes for someone else to uncover. I just hold burning questions and jagged theories to fit together like puzzle pieces without a grander picture to draw from. A picture that many before me have worked to put together. I hold its many threads that pull and pull, leading me into different directions, and spirals that sometimes spin me right back to the very beginning. Back to zaruki. Back to roti, mandarin pancakes, and pita––whose flatbreads belong to a people with history in Mexico, whose stories are roots that have been cast aside and buried, leaving tremendous gaps that span centuries. Ones that deserve to see the light of day and be revered, repaired, and remembered. Ones that we hold in the floured moons of our Mexican cuisine; a shred of light to a dark night of many stars we are now left to connect.

$= dv.el('center', 'Source: ' + dv.current().Link + ', ' + dv.current().Date.toLocaleString("fr-FR"))