19 KiB

| Alias | Tag | Date | DocType | Hierarchy | TimeStamp | Link | location | CollapseMetaTable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2022-02-21 | WebClipping | https://www.vice.com/en/article/4awqz3/why-are-letters-shaped-the-way-they-are | Yes |

Parent:: @News Read:: Yes

name Save

type command

action Save current file

id Save

^button-WhyAreLettersShapedtheWayTheyAreNSave

Why Are Letters Shaped the Way They Are?

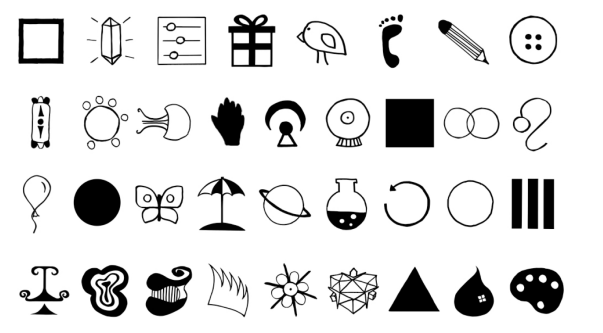

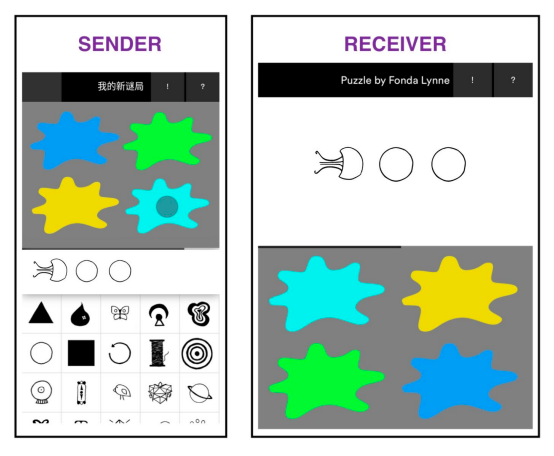

To tell a friend your favorite color, you might say the word, “blue,” or text them the letters: “r-e-d.” But what if you had to communicate a color to another person using only these symbols?:

Which would you choose? Are there any that seem more inherently blue, pink, red, or yellow? These are questions that players of The Color Game grappled with, which was developed to study the evolution of language by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

The Color Game app was downloaded by more than 4,000 people who spoke more than 70 languages from more than 100 countries. Over time, since it launched in 2018, the symbols acquired meaning as people used them to talk to one another—the players were creating their own language. Using an online survey, the researchers found that some symbols did evoke certain colors more than others, and the associations between symbols and colors were stronger in people who played regularly.

The Color Game did more than show how languages form over time, it violated a long-standing rule in linguistics: the rule of arbitrariness. In the subject of semiotics, or the use of signs and symbols to convey meaning, most students are taught about the theories of linguist Ferdinand de Saussure. He wrote that the letters and words in many writing and language systems have no relationship to what they refer to. The word “cat” doesn’t have anything particularly cat-like about it. The reason that “cat” means cat is because English speakers have decided so—it’s a social convention, not anything ingrained in the letters c-a-t. (According to Saussure, a language like Chinese, where each written character stands for a whole word, was a separate writing system, and his ideas were directed towards writing systems made up of letters or syllables.)

But the idea that words, or other signs, do actually relate to what they’re describing has been gaining ground. This is called iconicity: when a spoken or written word, or a gestured sign, is iconic in some way to what it’s referring to.

The Color Game doesn’t rely on iconicity alone—the interaction between players also helps create the language rules. At the start, some might say the crystal symbol is for pink, and others might think it means green. In a new study just accepted, publication forthcoming, in the journal _Cognitive Scienc_e, the research group leader Olivier Morin and his colleagues found that the meaning of the symbols became much more precise over time. But research now suggests that our languages are riddled with iconicity, and that it may play a role in language evolution, and how we learn and process language. Along with this evidence from The Color Game, in the last decade and a half, an increase in cross-cultural studies has re-upped the attention on iconicity, and pushed back against the doctrine of arbitrariness. “It is now generally accepted that natural languages feature plenty of non-arbitrary ways to link form and meaning, and that some forms of iconicity are pretty pervasive,” said Mark Dingemanse, a linguist at Radboud University, who said that he too learned in Linguistics 101 that “the sign is arbitrary.” “Iconicity has become impossible to ignore.”

Watch more from VICE:

In the Cratylus Dialogue, written by Plato, Socrates confronted this same linguistic dilemma: do names belong to their objects “naturally” or “conventionally," he wondered? Why do we name things the way we do? In 1690, John Locke wrote that because there are many different languages, and different words for the same objects, there couldn’t be a “natural” relationship between words and their objects. Saussure agreed in his seminal text, A Course in General Linguistics from 1916: “Signs do not directly evoke things.” Later, the linguist Charles Hockett wrote this one of the “design features” of language.

But iconicity has always been around. One familiar example is onomatopoeias, like “ding-dong,” “chirp,” or “swish”—words that sound like what they’re referring to. Those words aren't random, they have a direct relationship to what they represent. Yet, onomatopoeias were thought to be the exception to a wholly arbitrary set of signifiers, said Marcus Perlman, a lecturer in English language and linguistics at the University of Birmingham. This belief persisted despite hints that other words might have some connection to what they signified. In an experiment from 1929, the anthropologist Edward Sapir found that English speakers matched the pseudoword “mil” to small objects and “mal” to large objects. The higher frequency of the vowel sound /i/, or ee sound_,_ “is thought to give the impression of small size, given that small animals and objects generally produce higher-frequency sounds than large ones,” Perlman and others recently wrote in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.

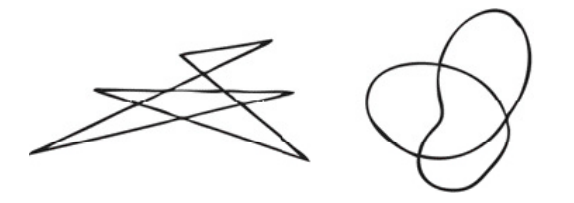

In 1929, Wolfgang Köhler introduced the takete/maluma effect, writing that most people match the word “takete” with an angular pointy shape and match “maluma” with a rounded one.

In the 1950s and 60s, studies found that you could present people with words from another language, and they would be better than chance at guessing what those words meant. One showed that when English antonyms were translated into Chinese, Czech, and Hindi, English speakers were able to match them up to the original English words more successfully than chance.

Yet these were still regarded as exceptions to the rule of arbitrariness, Perlman said. It took the gradual accumulation of more research over decades to change this, and the help of the belated recognition of sign language. “In the 60s researchers had the insight that sign languages were real languages; they weren't just gestures or pantomime,” Perlman said. “They were systematic languages as powerful as a spoken language.” Since sign language is very obviously iconic—signs are clearly related to what they are signifying—it helped bring the topic of iconicity back into the spotlight.

This led to the study of non-linguistic gestures, which are paired with speech, and are also frequently iconic. Finally, there was an expanded study of ideophones, a class of words that are depictive of an idea through their sounds. In English we have onomatopoeias, but in other languages there are much larger systems of ideophones. Japanese has words called mimetics, for example: the word gorogoro means a big object rolling slowly, but korokoro means a small object moving slowly.

There's a connection between the sound of the consonants and the objects they related to, Perlman explained. Voiceless consonants, or consonants that you don’t use vocal cords to produce like p-, t-, k-, and ch- are often associated with small sizes, and voiced consonants are associated with big ones; the unvoiced consonant k in korokoro is used to refer to a stone's lightness and g- represents the rock's heaviness.

“Originally these were considered on the margins of language,” Perlman said. “But now we've come to realize that these idiophones are in all languages. And they're much more common than we realize.”

One of the most documented examples of iconicity is the bouba/kiki effect, similar to the takete–maluma effect. People associate bouba with round objects, and kiki with pointy ones. Most recently, in November 2021, this was demonstrated in speakers of 25 languages and 10 writing systems.

Ćwiek, Aleksandra, et al. "The bouba/kiki effect is robust across cultures and writing systems." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 377.1841 (2022): 20200390.

Why is there such a connection? It might have to do with how it feels we say these words, along with their sounds. When a person says the word bouba, the shape of the mouth is more round than the word kiki, said Aleksandra Cwiek, the first author of the 2021 paper and a doctoral researcher at The Leibniz-Center General Linguistics. Words can feel spiky or round in our articulation of them; the /k/ sound is harder than /b/. With kiki, the k interrupts the air flow, and creates “a kind of spiky acoustic shape and it also feels kind of spiky in the mouth,” Cwiek said.

This effect extends beyond made up words. In 2021, researchers wrote about how words in English like ball, globe, balloon and hoop have more round vowels and sounds, compared to angular or spiky objects, such as spike, fork, cactus and shrapnel. In 2015, Perlman and colleagues had English speakers play a language game where they invented new words for opposing concepts like, “up, down, big, small, good, bad, fast, slow, far, near, few, many, long, short, rough, smooth, attractive, and ugly.”

A partner had 10 seconds to guess which of the ideas the new word was referring to. The participants did better than chance, and then the more they played, the better they got at guessing. Perlman said that people were able to guess because of the iconicity of vocalizations that are paired with the words.

In January, researchers found that words that express the texture of roughness are more likely to have a trilled /r/ noise, and other variations of /r/. In English the researchers looked at adjectives that described roughness, the ten roughest being: abrasive, barbed, jagged, rough, spiky, thorny, harsh, coarse, prickly, scratchy. (Compared to the ten ten smoothest words include smooth, lubricated, oily, slippery, silky, slick, polished, satiny, velvety, and fine.)

When they expanded their search to look for trilled /r/ sounds in a sample of 332 spoken languages, the researchers found this sound to be associated with roughness. Because the sound of a trill is broken up and discontinuous, the authors wrote that it may be associated with the “discontinuity in surface texture” of rough surfaces and textures.

“Apparently, once you have an /r/ sound, it is really hard to ignore its striking resemblance to the tactile sensation of 'roughness,' and so over time, unrelated languages converge on using that kind of sound for that kind of sensation,” Dingemanse said, a co-author on the paper. “I think of it as a bit like a gravity well: that association is so attractive and intuitive that it literally pulls at the fabric of our lexicons and makes the /r/-rough association surface in language after language.”

In English, our /r/ sounds have lost the trill in most dialects, yet we still have the relationship between /r/ and roughness. But there are cases where the trilled r has remained: The authors noted that the marketing campaign for Ruffles potato chips is, “R-R-Ruffles have R-R-Ridges.”

We are iconophiles at heart, Dingemanse said: “We love to connect form and meaning and we are experts at spotting all sorts of possible analogies. There are several mechanisms by which we do so but at base, they all come down to a remarkable ability to see structural resemblances between aspects of form and meaning.”

There could also be iconicity in what the letters themselves look like, and not just the sounds or gestures of words. In 2017, linguists Nora Turoman and Suzy Styles showed people who spoke unfamiliar languages different letters and asked them to guess which made the /i/ sound ("ee" in feet), and which was /u/ ("oo" sound in shoe). The participants were able to do so better than chance just by looking at the shape of the letters.

Evolutionary linguist Christine Cuskley and her colleagues have suggested that the shape of the letters in kiki and bouba contribute to the bouba/kiki effect. “One can readily see that the letters of the Roman alphabet used to represent kiki (k, i) are visually spikier than the more rounded letters for bouba (b, o, u, a), and the same also characterizes the contrast between words like takete and maluma,” they wrote. (Perlman said that they did a second experiment in their study on this, by showing people the written forms of bouba and kiki in different languages, and factoring out the roundness or pointy-ness of the letters themselves—the bouba/kiki effect still remained afterwards.) But Cwiek agreed that the connection between letter shapes and speech patterns is probably not always inconsequential. “I lean towards the view that there is something about the phoneme that motivated the graphene,” she said—meaning something about the sound of the word that influenced the shape of the letters that represent it.

Yet, we don't really know why our letters have the shapes that they do. Morin and his colleagues have recently created a new online game that will be investigating the shapes of letters, called Glyph. Of all the shapes that could be made with simple lines and drawings, letters occupy a very narrow area of that.

“We want to know how big that area is, why it’s this area rather than others,” Morin said. For example, letters have more “cardinals,” or horizontal and vertical lines than oblique lines, possibly because they’re more easily perceived by our visual systems.

Glyph will ask players to look at letter shapes purely for their forms, and come up with visual rules that connect different characters. It won’t be looking at iconicity primarily, but it will be assessing whether vowels or consonants are often grouped together. It's possible that letters that represent consonants look more like each other than they look like vowels—a type of iconicity.

Written language hasn’t received as much attention in linguistic research yet, said Yoolim Kim, a postdoctoral researcher working with Morin on Glyph, but it shouldn’t be discounted. Kim studies the Korean native alphabet of Hangul, which is an example of a predominantly iconic letter system. Each letter encodes visually for how it is pronounced. “The actual shape of the letters is meant to mirror the shape of your mouth when you pronounce that sound,” Kim said.

Aspiration is a linguistic term that refers to the puff of air created when you say certain sounds like t- (tuh), and Hangul represents that in its letters by using an extra stroke. “Every time you see that extra stroke, you can draw the conclusion that this letter will have that particular linguistic feature when you pronounce it,” Kim said.

For Kim, the iconicity of Hangul contributes to how she processes the language overall. “It has an effect on how it’s stored in my head, what I have to do to access and use it,” she said. It would be a mistake to say that all languages are entirely iconic. The bouba/kiki effect isn’t universal—in the 2021 paper they found that speakers of Romanian, Turkish and Mandarin Chinese didn't follow the bouba/kiki effect. Even onomatopoeia can vary culturally, like how the English word for the sounds a rooster makes is cock-a-doodle-doo, but in German it is kikeriki, and in French it is cocorico. Culture plays a role in iconicity, because one culture’s iconic relationship might not be recognized universally. In China, for example, they often use higher pitches for bigger objects and lower pitches for smaller objects, whereas it was the opposite in English speakers.

Language is most likely a mix of arbitrariness and iconicity, Perlman said, along with something called systematicity, when relationships form between words and meaning that aren’t necessarily iconic. (An example is words that start with gl- in English often are related to light, like glisten, glitter, gleam, and glow. There’s nothing necessarily light-like about the sound gl-, but the relationship is still there.)

Morin thinks of iconicity as the “icing on the cake” of language. It makes words more intuitive, more easy to guess. Iconicity might make languages easier to learn; Kim said there's a saying about Hangul, that: “A wise man can learn it in a morning, and a fool can learn it in the space of ten days."

In The Color Game, people used both: they built arbitrary conventions where the meaning of the symbols, building off iconicity that the shapes had at the start. “The iconicity is what the game feeds on, but it is refined by convention,” Morin said.

Still, this can be a very different way of thinking about words and language. Perlman said. It’s a move towards embodiment, or thinking about cognition in terms of the whole body: our gestures, how our mouths move, what we hear, see, and what we feel. Iconicity research changed the way Dingemanse thinks about language. “From a passive cipher that we just learn to apply (matching labels to objects) to an incredibly flexible and ever-evolving set of resources that changes, shapes, and even augments the way we think,” he said.

Language is all the more interesting by having both aspects present. “It's great that we can, say, use a sound like /r/ to evoke roughness to great effect (as we do in many spoken languages),” Dingemanse said. “But it's equally cool that we don't need to: that language offers us the possibility of a wide range of iconic associations without shackling us to them.”

Follow Shayla Love on Twitter.