|

|

---

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tag: ["🗳️", "🇺🇸", "🐘"]

|

|

|

Date: 2024-09-15

|

|

|

DocType: "WebClipping"

|

|

|

Hierarchy:

|

|

|

TimeStamp: 2024-09-15

|

|

|

Link: https://nymag.com/intelligencer/article/donald-trump-ear-campaign-assassination-attempt.html

|

|

|

location:

|

|

|

CollapseMetaTable: true

|

|

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

|

|

Parent:: [[@News|News]]

|

|

|

Read:: [[2024-09-25]]

|

|

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

```button

|

|

|

name Save

|

|

|

type command

|

|

|

action Save current file

|

|

|

id Save

|

|

|

```

|

|

|

^button-IExaminedDonaldTrumpEarandHisSoulatMaraLagoNSave

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

# I Examined Donald Trump’s Ear — and His Soul — at Mar-a-Lago

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

## The Afterlife of Donald Trump

|

|

|

|

|

|

## At home at Mar-a-Lago, the presidential hopeful contemplates miracles, his campaign, and his formidable new opponent.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

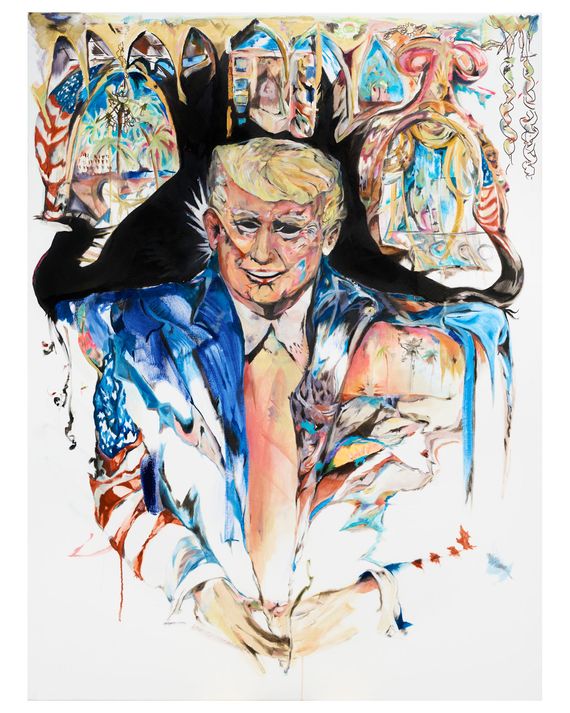

Photo: Jacob Holler. Art: Isabelle Brourman.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pink. An ovular rose. Big and smooth. A complex commonplace instrument. And, as far as these things go, a rather nice one. Isolated from the head and all that roils therein, and to which it is, famously and miraculously, still attached, you have to admit, if you can: It is beautiful. In Palm Beach, sunlight streamed through the window to find its blood vessels, setting the whole device aglow. Auris Divina, Divine Ear, protector of The Donald, immaculate cartilage shield, almighty piece of flesh.

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Donald Trump](https://nymag.com/tags/donald-trump/) raised his right hand and grabbed hold of it. He bent it backward and forward. I asked if I could take a closer look. These days, the former president and current triple threat — convicted felon, Republican presidential nominee, and recent survivor of an [assassination attempt](https://nymag.com/intelligencer/article/trump-rally-shooting-live-updates.html) — comes from a place of “yes.” He waved me over to where he sat on this August afternoon, in a low-to-the-ground chair upholstered in cream brocade fabric in the grand living room at [Mar-a-Lago](https://nymag.com/tags/mar-a-lago/).

|

|

|

|

|

|

## In This Issue

|

|

|

|

|

|

## Kamala Harris and Donald Trump

|

|

|

|

|

|

[](https://nymag.com/magazine/toc/2024-09-09.html)

|

|

|

|

|

|

[See All](https://nymag.com/magazine/toc/2024-09-09.html)

|

|

|

|

|

|

“Let’s see,” he said. He tapped the highest point of the helix. “It’s a railroad track.” He tapped it again. “They didn’t need a stitch,” he said. “You know, it’s funny. Usually, something like that would be considered a surreal experience, where you sort of don’t realize it, and yet there was no surrealism in this case. I felt immediately that I got hit by a bullet. I also knew it was my ear. It’s just a little bit over here — ” He used his hand to wiggle the ear. “Right next to — ” He gestured at the side of his head, at his brain, and raised his eyebrows. “It’s amazing.” He shook his head in disbelief. “And the ear, as you know, is a big bleeder.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

It did not feel surreal. Trump kept mentioning that. How unexpected it was, the matter-of-fact way in which he managed to process the attack as it unfolded. But on July 13 in Butler, Pennsylvania, he was tethered to the Earth as if by cosmic cord. He could not be pulled into the void. He was so clear about each moment of that afternoon. At Butler Memorial Hospital, he said, he asked the doctor, “ ‘Why is there so much blood?’” This was due to the vascular properties of cartilage, the doctor told him. “These are the things you learn through assassination attempts.” He laughed. “Okay, can you believe it?”

|

|

|

|

|

|

He can never fully see his own ear. He can never fully see himself as others do. I inched closer and narrowed my eyes. The particular spot that he identified with his tap was pristine. I scanned carefully the rest of the terrain. It looked normal and incredible and fine. Ears do not often become famous, and when they do, it is because they have suffered some sort of misfortune. Van Gogh’s self-mutilation. Mike Tyson’s cannibalistic injury to Evander Holyfield. J. Paul Getty III, whose kidnappers cut the whole thing off and put it in the mail. And now this, the luckiest and [most famous ear](https://nymag.com/intelligencer/article/republican-national-convention-milwaukee-mark-peterson.html) in the world. If you were the kind of person inclined to make such declarations, which Donald Trump is, you might call it the greatest ear of all time.

|

|

|

|

|

|

An ear had never before been so important, so burdened. An ear had never before represented the divide between the organic course of American history and an alternate timeline on which the democratic process was corrupted by an aberrant act of violence as it had not been in more than half a century. Yet an ear had never appeared to have gone through less. Except there, on the tiniest patch of this tiny sculpture of skin, a minor distortion that resembled not a crucifixion wound but the distant aftermath of a sunburn.

|

|

|

|

|

|

This is, of course, part of the legend. When [Ronny Jackson](https://nymag.com/tags/ronny-jackson/), the White House physician for [Barack Obama](https://nymag.com/tags/barack-obama/) and then for Trump, who now represents one of the most conservative congressional districts in Texas, described the injury, even the words he chose were delicate. The wound was “kind of a half-moon shape,” he told me. “There was nothing to stitch.” The bullet had “scooped” a small amount of “skin and fat” off the top of the ear. (By which he did not mean to imply that Trump has especially fat ears. “Everybody has fat and skin on top of their ears,” he said. “He’s got good ears.”)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jackson admitted he was responsible for the funny-looking bandage Trump sported at the Republican National Convention. Because the ear was inflamed and easily irritated, and because irritation caused it to start bleeding again, and because the shape of any ear makes it unwieldy to dress, his solution was to apply antibiotic ointment, then gauze to absorb blood, and then he secured the whole system with the envelopelike bandage that inspired so much derision and a brief niche fashion craze. “I thought that was pretty cool … I should’ve patented it,” he said. “I’m an emergency medical physician. I’m not a nurse,” he added. “I did the best I could.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

It had been three weeks since the rally. Since the bullet had launched from the barrel of an AR-15 and pierced the Pennsylvania sky. Since God’s hand had moved Trump’s head, as he had come to see it, sparing his temporal lobe, the part of the brain directly behind the top of the pinna, the medical term for the region of the outer ear that directs sound waves into the ear canal, responsible for functions related to emotions, memory, language, and visual perception. Since he had been tackled to the ground. Since he rose up, disheveled and defiant, to negotiate with his armed guards the terms of his exit from the stage. He wanted first to put on his shoes, which had been knocked off by the force of his defensive detail. He looked down at his feet. “Not these,” he said. “But ones like these. They were pretty tight. They weren’t loafers or anything.” And then he wanted to lead. That is how he saw what he did next. It was just what a leader would do. He recalled that when he looked into the crowd, he saw confusion spread across the faces of his fans. “They thought I was dead,” he told me. As a performer, he knew how to calibrate his actions onstage to address the needs of his audience. Blood running down his face, he raised his fist and punched the air. “Fight, fight, fight!” he said.

|

|

|

|

|

|

His iPhone, on the wooden table a few feet away, interrupted his story with the sound of Apple’s Reflection, its default ringtone. An aide got up to retrieve it for him. “Unless that’s important, I’ll just call back. Let me see — ” He took the phone and squinted at the screen. “Uh … Oooh!” His face curled into an expression of intense interest. He ignored the call but fixated on something else he had seen on the screen. “That was a big — that was a big day for us, today.” He was referring to [Kamala Harris](http://www.thecut.com/article/kamala-harris-women-movement-voters-organizers-grassroots-fundraising.html) picking [Tim Walz](https://nymag.com/intelligencer/article/tim-walz-kamala-harris-normie-running-mate.html) as her vice-presidential nominee. He asked to go off the record.

|

|

|

|

|

|

It was hurricane season, the offseason at Mar-a-Lago, and throughout our conversation, thunderclouds darkened the living room and then parted to reveal the light again. The historic estate is where Trump decamped a sore loser at the end of his one-term presidency three and a half years ago, having first failed in his campaign against [Joe Biden](https://nymag.com/intelligencer/tags/joe-biden/) (though he insists, still, that he won) and then failed in his efforts to overturn the results of that election through harebrained legal schemes and firing up a mob that attacked the United States Capitol and threatened to hang his vice-president. But that was all so long ago. Cocooned in this palace between the moats of the Intracoastal and the Atlantic Ocean, as he was impeached a second time and charged with 91 crimes and embroiled in many lawsuits, he became more convinced than ever of his invincibility. He plotted his return to power.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The “deep state” and its lawfare could not trap him. Members of his inner circle might be indicted, too, and some sent to jail, but he was different. He was an escape artist, better than [El Chapo](https://nymag.com/tags/el-chapo/) — who, unlike Trump, had been captured. Meanwhile, the Republican primary field turned out to be a joke, even easier to level than it had been in 2016. And best of all, Biden was weak and getting weaker. It had all been going so well, as he saw it. The day of the shooting, things could not have been going better.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The whole world finally agreed with what he had been saying for years: His opponent did not appear fit to serve. Compared to Biden, Trump looked practically like Zeus. And after his brush with death, his political future seemed all but secure. In the days that followed the attack, the Democratic Party panicked. The race was now a contest between undeniable strength and undeniable frailty. “Game over,” read one representative text from a party operative at that time. For so long, he had played the role of tough guy, and now he had finally done something so tough that he never had to pretend again. Even liberals had to admit that his response to the attack went pretty hard.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Trump was running for another term in the White House on the explicit pledge to do what he had not been empowered or wise enough to do the first time. The first campaign had been about promises and the second campaign about excuses. The third campaign was a threat. He would do what he wanted. He would be not just more powerful than he had ever been but more powerful than any president in American history. There would be tax cuts for the rich, regulation cuts for big business, mass deportations, a greater retreat from global commitments, and on and on — everything his opponents hated last time, just more and worse. Through a massive expansion of executive authority, independent agencies would enter his possession, most important of all the Justice Department, through which he vowed to exact revenge on his enemies in politics, law enforcement, and the media. For a while, all of this had seemed, to the roughly half of the country that would never support him, irrelevant. He was a fool and a felon, a disgrace to the office he had held and lost and now sought again. They didn’t want to hear about him or think about him again. Then, almost overnight after the shooting, the specter of another four years of MAGA set in.

|

|

|

|

|

|

In response, Trump received his belated prize for winning the debate, insult added to literal injury: a coup, as he saw it, that replaced the man he would almost certainly beat with the woman whose defeat was much less certain.

|

|

|

|

|

|

“Think of it,” he said. “So I went out and focused all this energy and talent and money and everything else on defeating him and then he starts going down very — you know, I was up by 16, 17 points in some polls. That’s when they went to him and said, ‘You can’t win.’ They told him, ‘You can’t win, and we want you out.’ It’s sort of never happened before. They took him out, and they put somebody else in. You know, they put a new candidate in, a candidate that we didn’t focus on at all. We never even got the — we had this big convention, and we were all focused on Biden, and now, now you take a look at it, and we were focused on a person that wasn’t running anymore. So it’s quite an unfair situation — but it’s okay.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

In Butler on July 13. Art: Gene J. Puskar/AP

|

|

|

|

|

|

The fish rots from the head down, and *Trump campaign,* like *Trump White House,* had never been a phrase that suggested order. Yet for the nearly two years it had been in business, since the candidate made the unorthodox decision to start running in the fall of 2022, the chaos that plagued the effort had been for the most part external. The campaign itself, headquartered in West Palm Beach, hummed along quietly compared to the 2016 and 2020 organizations, which had not hummed so much as blared like car horns in the night. Knifing, leaking, fuckups, general incompetence, firing and rehiring, outright regime change, scandal after scandal — those had been the subplots bubbling beneath whatever Trump himself had said or done at any given moment to upend whatever plan had been in place just the moment before. By this standard, Trump 2024 is a monastery (with the exception of that reported recent fistfight at Arlington National Cemetery).

|

|

|

|

|

|

In between rallies and media appearances, the candidate holds court on South Ocean Boulevard and casts about for ideas and advice, then, as usual, does whatever he was going to do in the end anyway, which looks like genius when it works and madness when it doesn’t. He is not exactly the kind of principal who can be staffed.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Susie Wiles and Chris LaCivita, who run the show on paper, are not veterans of either prior national campaign. Trump insists he’s happy with them, and he insists that recent personnel decisions, like bringing back known chaos agent Corey Lewandowski, are not corrective measures. “I just like him. Corey’s a character,” Trump said. “But I’m very happy with everybody.” There is nothing to correct, in his estimation, because he did not really lose the 2020 election, and in fact he performed better in 2020 than he had in 2016. “We got millions more votes in 2020,” he said. The whole thing, he maintained against all evidence, was rigged, and if he lost again in 2024, he would only commit to accept the results if he could be convinced that *this* contest was not rigged, too. “It’s a lot easier to concede than to say that you won and go and prove it when the system is against you,” he said. “All I’m asking for is an honest election.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

For all his marketing and manifestation prowess, it had been a strange fact of Trump’s political career that it sometimes took him a while to acclimate to a new nemesis. For much of the 2020 campaign, he struggled to engage with the character of Joe Biden. He could not decide even how to caricature him. Sleepy Joe? Crooked Joe? Glorified corpse or criminal mastermind? At his rallies — usually in airport hangars, a function of the pandemic — he devoted more time to campaigning against Hunter, who was not the correct Biden family member, or Hillary because, boy, did he miss her, or Obama, that all-time classic. A similar problem afflicts him now. When he referred recently to Obama as “Barack Hussein Obama,” a senior member of his campaign staff told me, “We’re so back.” More seriously, the candidate felt that he was supposed to be running against Biden. He had wanted to run against Biden. He was still, more often than not, running against Biden.

|

|

|

|

|

|

I asked him about an early nickname for Harris, Lyin’ Kamala. It was the same one he’d used before, most insistently against Ted Cruz, or Lyin’ Ted, during the 2016 primary cycle. It worked with the Texas senator because it had the benefit of both seeming and being true. I didn’t get a chance to formulate a question about why he would recycle material so closely associated with another politician before Trump interjected with a prideful bulletin.

|

|

|

|

|

|

“Well, I have a name. You saw the new name?” I had not seen it. “Kamabla,” he said. His communications director, Steven Cheung, who had said almost nothing for 57 minutes, piped up to say it too. “Kamabla.” Trump nodded. He gave me an expectant look, but I was confused. He repeated it again. “Kamabla.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

What did it mean? “Just a … mixed-up … pile of words. Like she is,” Trump said. I tried to pronounce it myself. *Kah-mah-bla*? I was still struggling. “She is — she is — ” Trump stopped what he was saying and stared at me with a look of grave concern and disappointment. “Well,” he said, “You have to see it to really understand.” This was perhaps a nickname meant for cyberbullying, not for conversation. “There are those that think it’s good … ” he said a bit uneasily. He nodded in Cheung’s direction. “You like it?” he asked. “It’s a good troll,” Cheung said. I asked Trump if he had come up with this one. He laughed a deflated kind of laugh, as if to minimize the importance of the answer. “Yeah,” he said, “I come up with a lot of things.” The name was soon retired.

|

|

|

|

|

|

As a first resort, Trump had called into question Harris’s racial identity. At a recent rally in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, a screen the size of a swimming pool projected a headline overhead for several hours about the historic nature of her election to the U.S. Senate, where she was the first Indian American woman to serve (she was not the first Black woman to serve). The stunt was supposed to imply that Harris was not Black enough and that she was, more generally, a fraud. Trump said he did not, in fact, talk about Harris’s race. “No. Not much,” he said. I began to raise the subject of the rally. He cut me off. “She is what she is. She has to determine that,” he said. He did not want to discuss the matter further. He launched into a riff about the economy (which is doing badly).

|

|

|

|

|

|

The whole subject of the vice-president annoyed him greatly. Actually, that was true for all vice-presidents, including his first one, whose theoretical assassination he endorsed, and his new one, whom he did not want to discuss much at all. “I think J.D. Vance is really — he’s really stepping up like I thought he would. I mean, he has been fantastic over the last few days.” He praised his book, *Hillbilly Elegy,* which he claims to have read. “It’s, uh, an opinion. A strong opinion,” he had told me in 2022.

|

|

|

|

|

|

I asked about the palace-intrigue stories that claimed now, just as they had in 2015 and 2016 and 2017 and 2018 and 2019 and 2020, that his advisers were struggling with a principal who lacked discipline. “We have been disciplined,” he said. “And they say ‘Don’t get personal,’ but remember, they’re personal with me. I mean, they call me weird. I’m not weird. I’m the most not-weird person.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

I asked if he would agree that he is an extraordinarily unusual person. “Unusual, but not weird. I think a very solid person. I mean, a solid person,” he said. Whom would he characterize as weird? “I think Tim Walz is weird. That guy’s the weird one,” he said. “And she’s Marxist, and that’s, that’s strange in this country because this country will never be a Marxist country. She’s actually — you know, her father is a big promoter of Marxism.” I was pretty sure Harris had been raised by her mother and does not maintain a relationship with her father, I said. “I don’t know …” Trump said. “Maybe that’s true, yeah. I just don’t know anything about it. I just know that he’s a Marxist professor.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

Later, when I asked one of his longtime advisers how it could be possible that the candidate did not appear to have received a very thorough briefing about his opponent, the adviser scoffed and related a story about the Friday afternoon in July when Biden taped his big postdebate interview with George Stephanopoulos. “I called and said, ‘I know a little about what happened in the interview. Do you want me to read it to you?’ He said, ‘What interview?’ He didn’t even know about it. I’m like, ‘Mr. President, there’s absolutely no possibility that you don’t know?’” He asked the adviser what network it was airing on so that he could make sure to TiVo it.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Donald Trump and the people who hate Donald Trump are in rare agreement on one thing: He has not changed. Now as ever, the very qualities and behaviors that result in his failures are the same as those that result in his successes. Why would he change a thing? About all matters relating to self, he thought this way. That his will alone determined his nature. That his nature determined his reality. That his reality — he was particularly proud of this — determined reality for everyone else. Change was an act of will, then, and an admission that something could be perfected, which was an admission that it had not been perfect to begin with, which was weakness.

|

|

|

|

|

|

“When I got hit, everybody thought I would change,” he told the crowd in Harrisburg in late July. “*Trump is going to be a nice man now. He came close to death.* And I really agreed with that — for about eight hours or so and then I realized that they wanted to put me in prison for doing absolutely nothing wrong.” In the end, he joked, he “was nice” for “three, four, or five hours.” Niceness was weakness, too.

|

|

|

|

|

|

In his RNC address, five days after the shooting, Trump announced that he would talk about it that night and then he would not talk about it again. It was “too painful,” he said. He needed to move on. But he kept talking and talking. He talked the way that he moved. Constantly, as a ritualistic exercise that would transform the events of that day into material, yet more rhythmic beats in the anti-hero’s journey he had been writing out loud for more than 40 years.

|

|

|

|

|

|

As narrator, he was in charge of his own life. In our conversation, he said he thought of himself as a kind of artist. And his life, his identity, was his art. “I’m a conceiver,” he said. “I’ve always designed things that worked.” He cited his buildings, his clubs, his books, his television shows — success had not visited him by chance, he said. “A lot of imagination goes into those things.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

When we talk about Donald Trump, we are often really talking about Donald Trump’s ears. Keeping Donald Trump focused on a single topic, even when that topic is related directly or indirectly to his favorite topic, Donald Trump, has long been a riddle so great that it has stumped some of the world’s most sophisticated and powerful minds. Even as his body idled, with the exception of his golf swing or his oddball bursts of movement inspired by the rhythms of the Village People, his monkey mind pinged and ponged, reacting to whatever information he absorbed through his hyperreceptors.

|

|

|

|

|

|

He is, more than most men, an animal. When he uses that term, *animal,* what he means to say is “subhuman.” He is referring, ordinarily, to undocumented immigrants and violent criminals. He does not like animals. Especially sharks, which he hates. He doesn’t like dogs. *Dog,* like *animal,* is a word he applies to others disparagingly. When he says “dog,” he means “pathetic.” What I mean when I say that Trump is an animal is that he operates, quick and pure, on instinct, driven by heightened sensory capabilities by which he absorbs information, processes it through a kaleidoscope, and spits it back out as only Trump can.

|

|

|

|

|

|

You can see him working when you look him in the eye. He is scanning, calculating what exactly he needs and how best to secure it through providing you with what he determines you want or need. The effect is at once prehistoric and futuristic. An intelligence that feels unevolved and artificial in equal measure. Part caveman, part computer. A regression and a leap forward.

|

|

|

|

|

|

It is popular to say that he does not have any beliefs, but what people mean when they say this is he has no principles. His greatest belief, the essential thing to understand about him, is his belief in his own mind. In its power to conceive and then to actualize. And he was unwilling to accept or admit that his mind was vulnerable to the influence of his emotions. He had never been comfortable being that human.

|

|

|

|

|

|

When I asked if he had been afraid in those moments when he heard the gunshots, when he felt the smack, when he saw the blood, he said, “I didn’t think of fear. I didn’t think of it.” In Trump’s understanding, fear is not a feeling but an idea that you may choose to entertain — or not. He moved right along to an idea he preferred to think of. “You know, I got so many nice calls from people I really don’t know. Jeff Bezos called. He said, ‘It is the most incredible thing I’ve ever watched.’ And he appreciated what I did, in the sense of getting up and letting people know,” he said. “I said, ‘Despite the fact that you own the Washington *Post,* I appreciate it.’ He couldn’t have been nicer. Mark Zuckerberg called up and said, ‘I’ve never supported a Republican before, but there’s no way I can vote for a Democrat in this election.’ He’s a guy that, his parents, everybody was always Democrat. He said, ‘I will never vote for the people running against you after watching what you did.’ So I mean, people really appreciated it. I don’t — I think it was very natural what I did. I think it was natural.” (Amazon did not respond to a request for comment. A spokesperson at Meta said, “As Mark has said publicly, he’s not endorsing anybody in this race and has not communicated to anybody how he intends to vote.”)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Had Trump dreamed about the shooting? “No, I haven’t,” he said. “It hasn’t had that kind of impact on me, and maybe that’s what’s good about being so busy.” The question activated a particular reflex, and he told me about his rallies, how he had held “numerous” events since Butler and how “successful” and “big” they were. “You know,” he said, “it would affect some people. I could understand how it would affect some people. Because you’re an eighth of an inch from really bad things happening. And no, I haven’t. I like not to think about it because I think that’s positive. You don’t want to think about it too much. But it was pretty amazing.” Did he ever remember his dreams? “A little. I think little sections of them, yes,” he said. “Sometimes, the concept of dreams, not as vividly, maybe, as some, some can tell you everything, but more of a dream concept or something sometimes. Generally, I don’t have too many of those dreams. It’s an interesting question because usually you don’t remember, like, the details of it, but you remember the concepts.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conceptually, he allowed that the shooting had proved to him the existence of an interventionist God. “Prior to this, I believed in God, but one — ” He jumped from his own thoughts to the lower-stakes thoughts of others. “This is actually an interesting situation,” he said. “I’ve had people that didn’t believe in God that said now they do because of this. No, this is divine intervention. And look, this is something.” He added, “It’s like the hunters were saying: If the deer bolts, you know, you’re ready to shoot. And sometimes the deer bolts and they miss. In a way, I bolted. You know, I guess my sons told me that sometimes you’re ready to end the deer. As you squeeze in the trigger, the deer is bolting. I sort of bolted. Yeah, it was an act of God, in my opinion.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

His mind turned to the image of the bullet shooting through the air. He was, still, more comfortable talking about himself than talking about God. “You saw the New York *Times* photo? The Doug Mills? The bullet’s red,” he said. “It’s got blood on it, and you see the blood being taken out with it. That’s an amazing photo. There’s so many different views. The one picture became iconic.” He was referring to the photo, by Evan Vucci, of his fist raised in the air with blood streaming down his face. “But are there numerous pictures that are iconic, or is it just that one specific one? Were there other pictures that were as good as that?” There was the photo of him on the ground, his bloodied face angled down and his profile cast in partial silhouette. He was familiar with the image. “Who took that one?” he asked. “Anna Moneymaker. She’s amazing,” I said. Trump nodded. “He did great,” he said.

|

|

|

|

|

|

But among those who have spent time with him in the wake of the attack — advisers and allies and people who qualify as friends, though most people who know him say he does not really have friends — there is a consensus: Whether or not he wants to, whether or not he can admit it, whether it seems outrageous to believe it yourself, Donald Trump, who has always been exactly who he is, who was not changed when his tabloid celebrity became reality-TV celebrity became political celebrity, who was not changed even by the office of the presidency of the United States, is nevertheless being dragged forward to the next phase of his evolution.

|

|

|

|

|

|

A longtime friend put it this way: “The religious stuff has always freaked him out, but maybe less now. I don’t know. All I know is I talked to him the night he got shot, and the first thing he said to me was, ‘The people in the audience were so brave.’ He didn’t talk about himself at all. Not at all. And I thought that was really interesting. In subsequent conversations, he’s mentioned God to me. I think it’s to be expected that he would be thinking about the world in a slightly different way.” This person added, “In some sense, he actually did turn his cheek, didn’t he? There’s something there, this idea of Trump starting to understand Christianity.” Another longtime adviser described his religious curiosity: “He has questions about resurrection and eternal life, good and evil, right and wrong and the afterlife and what happens. How does God decide who lives and who doesn’t during experiences like that?”

|

|

|

|

|

|

Early this year, Dr. Phil interviewed Trump. Trump told him, “ ‘I’ve watched your show. You’re not gonna get me to cry.’” Dr. Phil laughed. When the two men met again in late August for their second interview, he said, tears were no closer to Trump’s eyes but he displayed a new capacity and willingness to reflect and to entertain existential and religious questions. “It takes a dramatic event to change the course of someone’s personality and value systems,” Dr. Phil told me. He compared the process to “rerouting a river” or diverting the path of a bowling ball. “He’s certainly been different than I’ve seen him before, and he was different with me the second time than he was the first.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

From my perspective, it was true. He really did seem different. I have been interviewing Trump for almost ten years, and the Trump I have been speaking to since August is like no Trump I have ever encountered before. In person, it was impossible to ignore that even his face was different. He did not quite look like the same person. In a dark suit and dark tie slashed with thin red stripes, he was thinner than he had been during his springtime New York criminal trial. His hair was a paler shade of blond. His eyes were more feline. He wore an expression of perma-awe. He looked, in fact, like he had just been born. He sounded different, too. He spoke in a slower and more considered way.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Which is not to say that his consideration yielded the kind of results that might convert those who loathe him into admirers — or even change his grudge-motivated approach to politics. But it was the case that where there was once only action, there was now some effort, conscious or not, to relate. He had a softer presence. He laughed a lot. When others spoke, he listened carefully and with interest. He asked questions. The public saw this during his interview with podcaster Theo Von. Trump asked him about his experiences using drugs before he was sober. He seemed absorbed in what Von had to say. A longtime adviser said he was “more docile.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

His campaigns and presidency had been one long and unbroken series of complaints. His slogan, “Make America Great Again,” was a passive complaint in itself. *Why wasn’t America great anymore?* In power, his behavior had fueled an entire genre of stories about how he “seethed” and “fumed” and “stewed” on any given day over any given catastrophe or annoyance. According to just about everybody in close enough proximity to know, to be near him was to risk being bullied and blamed. It didn’t matter if you deserved it. He didn’t think that way. For Trump, something going wrong, or things just not going well enough, meant someone — though never him — had to pay.

|

|

|

|

|

|

But on the subject of his actual victimization, the biggest fuckup ever visited upon him, he was all grace. He focused now almost exclusively on everything that had gone right to conspire for his survival. The police had done an “amazing job.” The crowd was “amazing.” Everything was like that. “Amazing.” “Incredible.” “Amazing.” “Unbelievable.” “Amazing.” “I have to say, the Secret Service was very brave. I know they’re taking a lot of heat because they didn’t have somebody on that building, but when the bullets were flying, they came rushing. There was nobody that said, ‘Oh, let me stand back.’ And they were truly in the way of danger.” “The hospital was fantastic, Butler Hospital.” “The hospital was unbelievable.” “The doctors were unbelievable. You know, these are local doctors. They were unbelievable, unbelievable doctors. So it was amazing.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

Most of all, I wanted to know how he felt about a God that would intervene to spare his life but take the life of another man — Corey Comperatore, 50, husband and father of two children — and seriously wound two others. Had he thought about it? “Yeah,” he said. He talked for a while about Corey and what a big fan of his he was. And he talked about how a friend of his had given a million dollars to Corey’s wife, and how they had set up a fundraiser for the families, and how they had raised $5 million or $6 million. He kept talking and talking about the money. “I already gave the wife a million dollars, and she was great. I mean, look, she couldn’t believe it, but she would rather have her husband.” The check, he said for the second time now, was for a million dollars. “I don’t care how successful, it’s a check for a million dollars,” he said. “And I gave it to her. She was — she couldn’t believe it.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

I tried again. Had he wondered why he was spared and Corey Comperatore was not?

|

|

|

|

|

|

“No, I haven’t wondered why. I should wonder why,” he said. He looked off and he seemed to really be thinking. “I’ve been so — I’ve been working very hard on the campaign, and I also run a business during the time that I’m here, you know, with my family. It’s a great business. It’s an incredible business. But I am involved in running that, but mostly it’s the campaign because, you know, you have to do that. That’s got to be the focus. And my children run the business now and do a good job. Eric runs it, and Don helps him and runs it, also different aspects of it.” He was still looking off. “But no, I’ve never asked myself that. I’ve never thought of it. I don’t like thinking about it too much, because it’s almost like you have to get on with your life. So I don’t really like thinking about that too much.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

Setting up for a portrait of Donald Trump at Mar-a-Lago in August. Photo: Isabelle Brouman

|

|

|

|

|

|

There’s definitely more work to do,” another person close to Trump said about efforts to get him ready for the September 10 debate that is potentially make-or-break for both candidates. “His study habits and willingness to prep in depth always has been challenging, but I would not expect an unprepared Trump for the debate. If she doesn’t piss him off, he can stay on message.” Although he was different after the shooting — “It’s impacted him in a really good way and in a really weird way,” this person said — “there are moments where he’s still him and he gets pissed off. I think this switcheroo, if you will, has been more difficult. He felt like he would have walked away with this easily, and I think he would have also, but I’m like, ‘You deal with the hand you’re dealt. Not the one you wish you’re dealt.’ And I think he’s come to terms with that reality and he’s dialing in to win.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

According to national polling averages, Trump is now down by roughly two points against Harris. And it’s one or two or three percentage points that will determine the winner in the swing states that will determine the presidency. In the absence of outright infighting, there were still oppositional factions in the campaign — the insiders versus the outsiders, the MAGA diehards versus the more practical professionals — and their disagreements came down to perceptions of purity and its value as a means to win.

|

|

|

|

|

|

There is one view that the MAGA movement is big enough on its own and that the campaign should be an effort to appease and energize the base. There is the other view: that victory will require a more accessible pitch that redefines MAGA as more generally anti-Establishment, a catchall movement for anyone unhappy with the existing system and the official narrative, whatever that means to them.

|

|

|

|

|

|

This is where Democrats turned independents Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Tulsi Gabbard, who have each endorsed Trump and been named co-chairs (alongside Vance, Don Jr., and Eric) of his presidential transition, come in. The campaign is now referring to MAGA as a “unity party.” Kennedy was drawing between 4 and 5 percent in some swing states before he pledged to “Make America Healthy Again,” a coup for Trump, whose leadership during the pandemic raised suspicions and inspired contempt among vaccine skeptics and big-government opponents on the alternative left and right of the political divide.

|

|

|

|

|

|

In speeches now, in between his meals from McDonald’s and his compulsive consumption of Diet Coke, Trump is talking about food quality and public health and forever chemicals — subjects of huge interest to Kennedy’s eclectic base. He doesn’t have to live it; he just has to convince those concerned about these issues that he now sees them as part of his general challenge to the power structures that he did not challenge the first time he was in charge of the government. It’s an uncomfortable sell, but the campaign is making a bet that voters — younger, politically alienated or inactive ones especially — might find themselves MAGA-pilled, if they weren’t before, after experiencing a more human-seeming Trump on one of the hugely popular podcasts he has appeared on recently, including with Von, Jake Paul, and Lex Fridman. If the campaign succeeds, Trump will appear by November to be the king of broader anti-Establishment, anti-woke culture, hip to the wisdom of bitcoiners and biohackers, tradwives and cybertruck drivers, naturalists and futurists, UFC fighters and stoic philosophers. “If he can just get a little groovy, he wins,” his longtime friend said. “And Trump is the only person alive who still says *groovy.* He’s a ’70s guy.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

Trump was telling me how much people prefer to watch his speeches and attend his events compared to his opponent. He filled arenas, he reminded me, “and don’t forget: I don’t call an entertainer like she did.” His crowds were there for him, he said. “I don’t have a guitar, but I’m the entertainer.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

There is only so much room for either candidate to grow their support. And if these appeals aren’t enough for victory in the face of the Democratic Party’s historically successful fundraising efforts and still-improving poll numbers, Trump’s only hope may be another divine intervention. Not that he’d admit it. “We’re leading in many of the polls,” he said. “I think most of the polls, despite the honeymoon period, which is soon going to be ending, I think. I hope.” He did not say he was praying for it. But others in his world of informal advisers and supporters are openly doing so. “He’s not going to win unless it’s the same forces that turned his head when the sniper fired — that’s kind of my view,” said the longtime friend.

|

|

|

|

|

|

A few weeks later, during the Democratic National Convention, we were talking on the phone. He still sounded and seemed different. But was he? I’m a big-time believer that people can change, though I know they rarely do. It was in this spirit that I mentioned to Trump that recently I had seen for the first time the modest home where he was raised in Jamaica Estates, Queens. What did he think when he considered his journey from there? “I’m honored. I’m honored, and I’m honored that, you know, it’s such a big subject. It’s like they don’t talk about anything else. Olivia, you watch, like, their convention, all they talk about is me. You know, all of these other networks, all that. This is going on for eight years now. You know, more than eight years. It’s like they don’t talk about anybody, anything else or anybody else. It’s a whole thing. It’s Trump. And it’s been that way for, really, nine years now. I’m honored by it. I used to be angered by it. By, you know — that’s why, like, you look at MSDNC, you look at Fake News CNN, all they talk about is Trump. Every show, they go, ‘Look at us!’ That they go from one thing to another thing to another thing. The only thing is, Trump’s involved in every one of them. And I started to say that I’m actually honored by it. It’s an honor. It’s never happened before. There’s never been anything like this before.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

I Examined Donald Trump’s Ear — and His Soul — at Mar-a-Lago

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

`$= dv.el('center', 'Source: ' + dv.current().Link + ', ' + dv.current().Date.toLocaleString("fr-FR"))` |